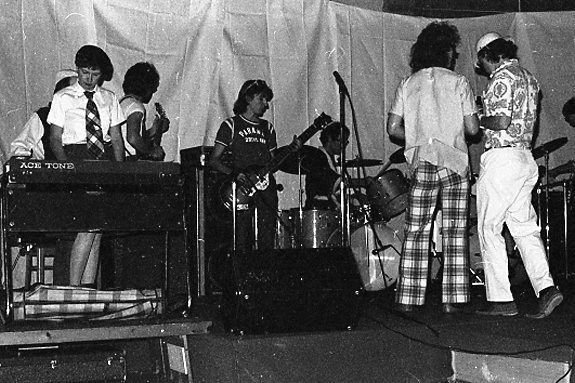

Oh Those Pants! Owen Burgess, Rob Lusk, Martha Johnson, Chris Perry, Ed McLaughlin, John Ford, David Millar, Kimmo Eckland (l-r). Not shown: Ross Edmonds, Jim Hughes and Peter Chapman. From Owen Burgess’ collection.

[This is the third section of the blog post “how the Queen Street West scene began, pt. 2: OCA bands”]

You know, Oh Those Pants! were amazing. They did covers, right? But they did them brilliantly. They had two lead singers and two drummers — they had, like, twelve pieces up there on stage. And it just was fabulous; we really enjoyed it. And that Thornhill sound, you know, made an impression. [Ian Mackay]

Instead of like writing some song for their band, they would just, like, use kind of ready-made songs. You know — what’s the one — “At the Boardwalk” or “Palisades Park,” and “The In Crowd.” They seemed like decades before, but in fact in retrospect they were only ten year old songs at that time, or slightly twelve. So they just used these song forms as kind of a structure that their gigantic band could wail away on while a lot of crazy stuff happened on stage. [David Clarkson]

[Oh Those Pants!] were the first band I’d ever seen [in the nascent QSW music scene]. Seeing them was kind of when you started to see the world turn in a way. [Anna Bourque, quoted in Worth 2011: 36]

The story of Oh Those Pants!, the first significant mark of the Thornhill Sound on Toronto music, reflects the joining of two cohorts of Thornhill Secondary students; the first brought the OCA affiliation, the second the musical momentum. In 1974, Owen Burgess and John Ford (late of Swami & His Swinging Turbans) enrolled at the Ontario College of Art in the same entering class as Mark Gane, Ian Mackay, and David Clarkson — other key figures in the story to come. (Toronto singer Mary Margaret O’Hara also enrolled at OCA at some point around this period, apparently.) Ford was quickly disappointed.

What I really wanted to do was experimental graphics and visuals, and maybe get into some film stuff. Film was just starting out as a college thing, at least at OCA. They shot 16, and you had to process yourself and all this stuff. So because I learned so much on the job, I went into OCA and I registered. This was like ‘74. I was accepted and ended up taking all these courses that were like logo design and graphic design that I kind of already knew how to do that stuff. You know, I had a good start at it… So after one term, I dropped out and got a job at the post office in Thornhill to save money to go to Europe for three months. And Rob Lusk and I went to Europe, and at that time I only knew Rob as an acquaintance. We were both looking for somebody to go to Europe with, so we just went. [John Ford]

Meanwhile, a set of younger musicians affiliated with the high school garage band the Rhumba Kings were making noise again in the basements of Thornhill.

The band’s real genesis began between Jim Hughes and Robert Lusk, who, of that group, were a little bit younger, a year or two younger than me, I guess. They had started just by hacking around themselves in the basement. Then people kind of started to come together with them. So the two of them were, if you had to say who started the band, it would be Robert and Jim. Lord Lust and Jack Ladd: those were their stage names. And that was of course just as we were all finishing university, and as we all sort of gravitated down, that’s when we — like, I started playing with those guys in Thornhill, and then within a few months, a year not even probably, we were all downtown. [Chris Terry]

John Ford and Rob Lusk had been two grades apart at Thornhill Secondary; their European sojourn strengthened their weak ties and created momentum for the new band. By early 1975, Oh Those Pants! materialized to quickly become the prototypical “OCA band” – art-inspired, musically adventurous, wise-cracking, and socially connected. At its core were six Thornhill musicians: Rob Lusk (a.k.a. Lord Lust – vocals), Ford (a.k.a. Buck Cheeser – guitar), Jim Hughes (Jack Ladd – guitar), Ross Edmonds (Riki Slain – bass), Owen Burgess (Art Treasure – guitar), and, fresh off the musical sidelines, Chris Terry (X. Perry Mental – drums).

The story was, as far as the name — I wasn’t there, but there was another friend of ours named Karen Kiddy who was a really, really fun person. And they were out drinking one night, and she saw somebody’s pants that were amazing, and she said, “Oh, those pants!” I mean, there’s not much to it, but that somehow — like, I think probably Owen said, “You know, that’s a great name for a band. So we’re gonna call the band Oh Those Pants!” [John Ford]

The Pants’ first performance was at a Sigma Chi fraternity party at the University of Toronto in the spring of 1975.

I think we played the first party that we played at was a frat party at U of T that somebody connected us to. It was like a Greek letter frat house, and we played at their party. And I don’t know, everybody was so drunk that it didn’t matter what we played, but we had a really great time. That to me was when Oh Those Pants! really took off. [John Ford]

Initially contented to play off-beat covers, Oh Those Pants! had neither serious ambition nor a real sense of its audience in its first year. Things only began rolling in 1976, following a gig secured by Michael Robertson, ex-Dog and Thornhill, whose art career secured him a loft at downtown artist space Coffin Factory Studios.

Michael Robertson had by then moved down to a studio space. So there’s a building in Toronto on Niagara Street, 89 Niagara Street, which was a fantastic loft studio space. It was just full of artists. It was just like one hotbed of artistic activity. Michael said, “Well, why don’t we have some parties? Let’s have a party. You guys can come and play.” […] And the party that Michael prompted us to go to, we ended up giving it a name. We called it an “art attack”… At the same time, Burgess was in like second year at OCA, and through OCA he had met a bunch of people. They had seen us play [the frat] party like a week or two before that. And it became known to us — this was after the fact — it became known to us that they had come to this art attack party specifically with the agenda of seeing us and staking their claim. They wanted to be in the band. We kind of knew them a little bit, thought they were cool guys. [Chris Terry]

The “bunch of people” Terry refers to included Ed McLaughlin and Kimmo Eckland (a.k.a. Kimo Eklund), two OCA students recently immigrated from Scotland and Sweden, respectively. McLaughlin and Eckland enthusiastically imposed themselves on Oh Those Pants! as vocalist (stage name: Eddy Lagrande) and drummer (stage name: Mr. Helsinki), regardless of the fact that those positions were already taken.

So we went from one lead singer to two, and one drummer to two. And this started kind of a really crazy trajectory for the band, which was suddenly it became a big project, and then it started to take on this sort of artistic endeavor rather than just be a laugh. [Chris Terry]

Kimmo Eckland and Ed McLaughlin, who had nothing to do with the Thornhill scene, brought a whole new group of people together, a whole new energy to the band. They were relentless proselytizing for putting gigs together, you know, creativing events for us to play at. They were just all about getting the band out and partying! Basically it was just to party. A party band — that’s just the way it was. [Owen Burgess]

Eckland was a member of the controversial queer art collective Shitbandit with fellow OCA student Ron Giii.

Kimo and a bunch of other guys made films on horses. They didn’t know how to ride horses. His stuff was so bad it was good. Everyone was taken in by this incredible guy. [Ron Giii]

A lot of those guys were taking film at OCA, so there were films that they were making, of which there’s one you should probably see if you haven’t been told about it… It was just kind of a crazy, historical drama about these brothers — it was called “The Idiot Brothers” — and that was to say there was a whole cadre of people who were fans of Oh Those Pants!, or they were in Oh Those Pants!, or they were involved in the film that was being made and they were partying, in the summertime too. It was a whole kind of like collective. [John Ford]

They were too cool to do paintings. They were studying, like, you know, experimental filmmaking with Super 8 movies and stuff like that. I think that could have been the reason they had a band, because they wanted to do a giant light show, I suspect. It was all a movie, or they wanted a reason to shoot movies. So their show was not just them playing. It was basically this whole spectacle of, you know, crazy dancers and lighting and movies and noise. [David Clarkson]

By spring three more people had joined “the Pants,” starting with OCA student David Millar (stage name: Jacky Dave – guitar and sax). Millar was an assistant to Udo Kasemets and was often found in the OCA’s Sound Lab, along with Mark Gane and Ian Mackay.

Yes, [Millar] was [in Oh Those Pants!], very much so, playing saxophone and teaching us about aleatory music. An aleatory rock band! [Owen Burgess]

In the green room at the Glen Eagle Golf Club: DC Walker, unidentified person (obscured), Jim Hughes, Peter Chapman, Lauri Towata, Micheline Scammell (l-r). From Owen Burgess’ collection.

Another sax player was drafted, about whom I could find little: Peter Chapman (stage name: Peter C). Finally, Thornhill friend Martha Johnson (stage name: Cerise Sauvage) joined in on keyboards and backing vocals — her first time playing on stage for strangers.

Oh Those Pants! used to get paid in beer… It was just a party band really. We would have a theme every night like wrestling or the beach. [Martha Johnson]

Whatever you do, don’t play rock and roll in a full wetsuit. You can’t get it off. [Owen Burgess, quoted in The Last Pogo Jumps Again]

My research indicates these eleven (!) members comprised the most robust Oh Those Pants! line-up. The band would persist through the rest of the decade in various and often smaller permutations, often called into action for special occasions and not at the exclusion of members focusing their attentions to other bands. However, there are claims that other people, Steven Davey for one, played with the group:

There were two drummers. Neither of them could play. Martha was the keyboard player and had never played before in her life. I played the saxophone and didn’t know how. But we’d just play these old rock’n’roll songs that everybody sort of knew, so you didn’t even have to rehearse them and the audience would get up and dance. [Steven Davey, quoted in Worth 2011: 36]

Though Steven Davey wasn’t a formal Pant member, definitely he was working with everybody. I mean, we all end up working with him at some point. [Chris Terry]

I think John Corbett might have played bass sometimes, maybe? […] You know, like, in a party atmosphere, anybody might have joined in for percussion or grabbed a guitar. But I don’t think there’s anybody else that were members of the band. [John Ford]

When the original bass player Ross Edmonds dropped out, I ended up being bass player for both the Cads and for Oh Those Pants! [John Corbett]

As Steven would say, we were there before anybody. And that’s why he held Oh Those Pants! in some sort of reverence. You know, he was a tireless, tireless campaigner for that band being one of the originators. Because there were so many of us, and we drew in so many other people. [Owen Burgess]

The Country Lads: Whereas about half of Oh Those Pants! were actual OCA students, their Thornhill connections opened the door for friends with no OCA affiliation to be likewise labeled “OCA bands.” A case in point is the Country Lads, a roots-rock unit that brought Johnny MacLeod onto guitar in a new role as frontman and moved his former Unity Theatre bandmate Carl Finkle over to bass.

Country Lads: Carl Finkle, Dave Taylor, Johnny MacLeod, Bill Priestman (l-r). From Owen Burgess’ collection.

Yeah my friend John MacLeod wanted to form a band, and he didn’t have a bass player. John was a guitar player. He had a small-scale Fender bass, so he says, “You can play this.” Because I had played guitar, right? So transitioning from guitar to bass wasn’t that big of a deal, and I thought, “What the heck; this is fun.” So he and I eventually formed this group with a couple of other people called the Country Lads. And we were doing an early rockabilly almost — we didn’t know we were doing that, but that was virtually what we were doing. And we were doing all the covers of the country stuff, the Johnny Cash stuff and that, again with a rock edge to it. And that’s how I got playing bass. [Carl Finkle]

We went wild for Hank, Buck Owens. You know when you find Hank Williams and you can’t believe it, right? We were all gung-ho about this. I guess at this point I had come back from England, and that’s what I wanted to do. So we depped Carl in, my brother started on drums, John Corbett was on drums, then a great local guy called Dave Taylor, who doesn’t really play much anymore. [John MacLeod]

Yeah, we just played around and hacked out. We played one gig at a Ontario hospital for people with pretty severe disabilities at one point. Best gig we ever did. We could’ve played the same song all night, these people just were so totally — the kind of people who were sort of strapped into walkers and had to wear hockey helmets because otherwise they would bash their head against the wall repeatedly. So it was that kind of place. And they went nuts. We got this really lovely letter which is somewhere in my archives from the people going, “Thank you very much.” You know, we did it for free. Carl was able — Carl’s family had a sort of audio distribution place, and so we managed to sort of cobble together a little PA system for that. And it was just a lot of fun. I was really into it. One of the most gratifying gigs I ever did. [John Corbett]

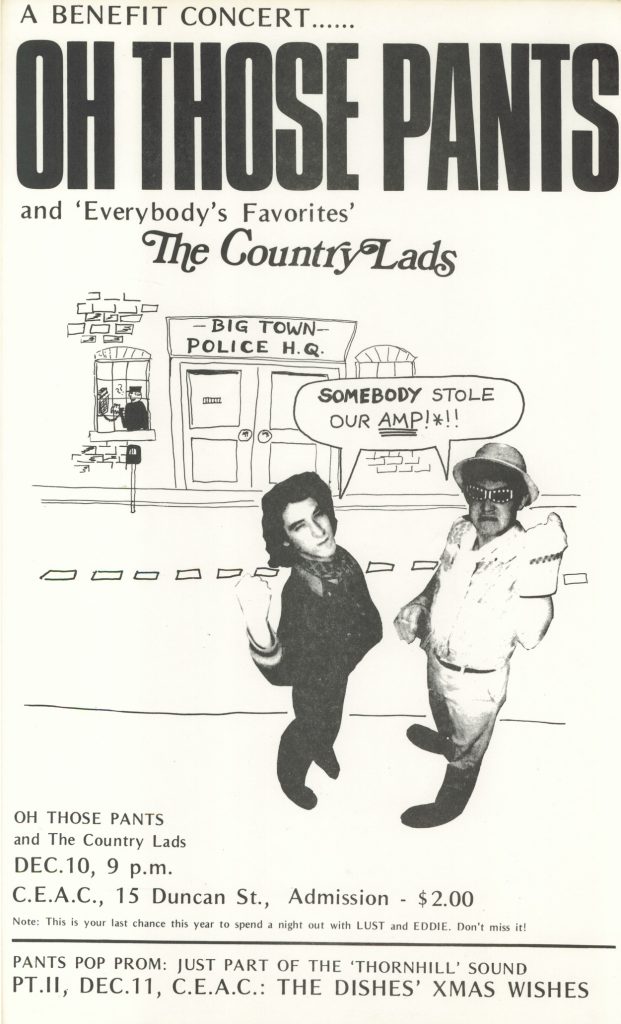

The Country Lads left little legacy themselves (although film footage is rumored to exist), but they were notable, first, in marking the musical coming of age for Johnny MacLeod, who became one of QSW’s indomitable frontmen and behind-the-scenes doers. The band also maintained the connections among the Thornhill Sound, including the relationship between former Marzipan and future Muffin bandmates Finkle and Martha Johnson, whose band Oh Those Pants! had the Country Lads open for them at least twice. One time was at the Glen Eagles country club in Bolton, a metro suburb not far from Thornhill.

In fact, we did a show together of Country Lads and Oh Those Pants! at a… [chuckles] This was for an instructor at OCA who was a member at a country club up in, like, north of Toronto. I think it was Woodbridge. And he was — he was pretty crazy. So he got Oh Those Pants! and the Country Lads to play at this dance at a country club. [John Ford]

The flyer for this event (shown at the beginning of this blog post) further announces a beauty pageant — whether real or General Idea-style fantasy, it’s unclear. In fact, no one I interviewed seemed to recall this. (Above, John Ford is even mistaken about the country club’s location.)

“OCA bands”

What the Glen Eagles country club event does indicate, however, is the casual intermingling of OCA faculty with students and student-musicians, first and foremost at the Beverley Tavern down the street on McCaul and Queen Street West.

This was a time when frequently part of the education process involved spending a considerable sum of time at the Beverley Tavern with your professor, right? This was the old guard of the OCA guys. In the traditional sense did a lot of work get done? I’m not so sure. But were there a lot of discussions about what is art? Absolutely. And these were guys, like, Gordon Rainer was around in those days, a lot of the guys from the late 50s abstract scene in Toronto. [John MacLeod]

Like some teachers, some of the drinkier teachers at OCA would just take the class down to the Beverley and would just drink and talk about art, you know? [John Ford]

Yeah, but having said that, that’s not changed. I take my students across the road to the pub at the Fifth. They’re graduate students, so at least I know all of them are drinking age. [Laughs] Because some of our students are not in the undergraduate department. And, you know, we’ll actually sometimes go, “Okay, we’ve done enough today, and this would be a much better class if we continued in the pub.” And that happens from time to time. You know, and then of course you’ve also got students that don’t drink, but they come along as well. [Martha Ladly]

The perspective of Martha Ladly — an Etobicoke girl, so someone I haven’t introduced yet, but also an OCA student and (at this point in my story’s timeline) future Muffin — is especially useful here because today, Ladly is herself an art professor at OCAD University. When asked to compare how OCA students have hung out on QSW today versus back then, she explains that the their infiltration of the neighborhood wasn’t just a function of the Toronto zeitgeist, but also the institution’s longstanding lack of public space at a time when faculty and students had real need to mingle and collaborate.

What you learn at art school is as much hanging out with people, in conversation, in social time, as it is in the classroom or in the studio during more structured time. Particularly because so many of our students have to commute, and because we have no social space in the university — none at all. We had very little space [in the 1970s, when Ladly was an OCA student], either, but we at least had this auditorium canteen place where we could go eat together. And we also had an atrium where we could hang out together. [Today] we do have that place underneath the Sharp Centre where students hang out. And now that Grange Park has finally opened up, the students bleed into the park, too, which is really good. But we don’t have a pub, you know? [For that reason, back then] the Beverley was the school pub. [Martha Ladly]

Oh Those Pants!, the Country Lads, and a few other musical groups were thus deemed “OCA bands” by early QSW scenesters by virtue of their frequent appearance at the venue where adventurous new rock music could be heard in the days just before the QSW scene blew up: the OCA auditorium-slash-canteen.

An OCA band would be a band — it’s very simple: we had that fantastic auditorium with this fantastic stage. We had a student-run pub there, in the auditorium. It didn’t have seating; it was just a big gym. You’ve seen it, I don’t know, like in “Back to the Future,” where the guy does the Chuck Berry walk. It’s that kind of situation. And so, it seemed like at the time it was anybody who hung around in the pub and got drunk enough and said, “Let’s play together, and what a joke it would be to, let’s arrange to play here and we’ll just invite everybody here.” […] So those were OCA bands. But they were basically the people that were sitting there drinking — the students who were sitting there drinking like this fifty cent draft beer in the auditorium like instead of going and doing our homework. [David Clarkson]

As I often say to people, I never went to OCA as a student, but it was certainly one of the centers of my social life. For example, Chris Terry’s partner from way back when, Deborah Pollovey, she used to cut my hair. She was on security, and so she’d just, you know, pull a chair out into the hallway and throw down some newspapers and she’d cut my hair. So it was that sort of level. I was never there [at the OCA] in the daytime, always there at night. [John Corbett]

Next – the Dishes open up QSW to new music.

ROAD MAP TO QSW:

how the Queen Street West scene began, pt. 1: the Thornhill sound

the Thornhill sound

suburban dream

precocious urbanites: the Ross sisters

the starmaker: Steven Davey

the bands of Thornhill

how the Queen Street West scene began, pt. 2: OCA bands

the Thornhill sound leaves home

how art came to QSW

Oh Those Pants! bring the Thornhill sound to OCA

the Dishes open up QSW to new music

punk and art: the Diodes

the Thornhill sound set loose on QSW

the last house band: Martha and the Muffins

sources, citations and updates