In this year of awful news, I wonder if we’re currently experiencing what evangelical Christians call the rapture. Only now the evangelicals remain on earth, while great people whose contributions made the world a better place are passing away almost daily. Just reviewing the music world memoriam since January: David Bowie, Lemmy, Glenn Frey, Blowfly Pierre Boulez, Dan Hicks, Vanity, Nana Vasconcelos, Frank Sinatra Jr., Phife Dawg, Prince, John Stabb, Guy Clark, Dave Swarbrick, Bernie Worrell, Scotty Moore, Alan Vega, Prince Buster, Leonard Cohen, Leon Russell… And now David Mancuso.

David Mancuso’s contribution to music is signified by his page-one status in Tim Lawrence’s book Love Saves the Day: A History of American Dance Music Culture, 1970-1979. At the beginning of the new decade, Mancuso hosted private house parties at his downtown NYC loft at 647 Broadway Avenue, where dancing to music emanating from a superlative audio system was the main focus. These loft parties, later institutionalized under the nightlife moniker “the Loft,” set in motion the sound and experience we associate with modern nightclubbing.

Ostensibly the disc jockey, Mancuso’s genius lay in curating content and cultivating communion for the dancefloor, well beyond the specific roles associated with “the DJ.” He culled deep cuts and left-field tracks that inspired dancefloor revelation in a pre-disco world. Working with sound engineer Alex Rosner, he developed a sound system that broke new ground in nightclub audio experience. Mancuso created new possibilities of narrative and theme from the DJ’s playlist. Famously, he didn’t blend his records together, instead letting tracks run all the way to their final fade-out, the silence signalling the end of a particular sonic episode. He cultivated a dancefloor democracy that contrasted with the high-status nightlife scenes reported on society pages. Loft parties were invitation-only but free, Mancuso carefully selecting a balanced mix of races, genders, sexualities and classes. The Loft served the simplest of refreshments: punch, snacks, and no alcohol. The drugs and libidos that attendees brought with them often heighten the collective release on the floor, but Mancuso had “an alternative set of priorities,” as Lawrence writes.

“The loft chipped away at the ritual of sex as the driving force behind parties,” says Mark Riley, one of Mancuso’s devoted followers. “Dance was not a means to sex but drove the space” (pg. 25).

This much is recognized by dancefloor devotees and scholars: the line through disco, house music, and finally all stripes of underground dance music that provide dancefloor ecstasy and subcultural shelter can be seen to start with David Mancuso. But his contributions to dance music went beyond the Loft. His musical taste and promotional effort helped sketch the musical parameters of disco in its earliest days; among the songs he helped break through in America was Cameroonian saxophonist Manu Dibango’s “Soul Makossa.” Mancuso inaugurated the first record pool for NYC DJs, in which music labels distributed new releases to a certified, mutually regulated group of disc jockeys; this arrangement, copied in other cities and scenes, tilted the aesthetic and economic balance of power between recording artists, music industry, and DJs toward the latter.

I never went to the Loft. However, I did encounter David Mancuso maybe two times around the year 2000 at the East Village record store Dub Spot Records. I haven’t had luck finding internet history on this store or Mancuso’s role in it, as the search phrase “Dub Spot Records” has been usurped by a 5th Avenue DJ/producer school. I’d love to learn more about this store, because for my money, Dub Spot was one of the city’s most inviting and eclectic record stores, in a period before 9/11 when underground dance music seemed to dominate the musical landscape of NYC.

Let me go back a bit. In August 1999, I moved from Los Angeles to Poughkeepsie, New York to take my current job at Vassar College. Weekends in Manhattan with my friends Rey and Rachel kept me afloat during a precarious state of anomie; within a few months my marriage would disintegrate under the long distance. Divorced and uncommitted, I bought two Technics 1200s, a Gemini mixer, a PA, and two loudspeakers. Rey and I decided to become DJs: I had the equipment, Rey found the opportunities, and together we hit record stores to build a collection of house, techno, and 80s music.

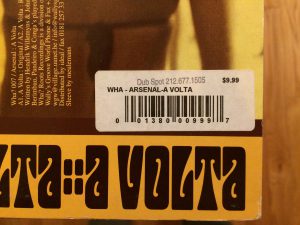

The two of us amateur DJs, we were hopelessly out of our league in NYC. Thank God for Rey’s friends, many of them nightlife denizens who didn’t seem to mind our turntable car crashes, whether out of generosity or intoxication. One of my cherished moments in this period was the Y2K New Years Party at Rey’s apartment, where the crowd’s sails caught particular wind with a Brazilian house track I had just procured, Arsenal’s “A Volta” (Marino Berardi Beach Mix).” I was eager to return to the record store where I bought it.

I walked into Dub Spot Records, located on 13th Street between A & B Avenues if I remember correctly. There weren’t a lot of customers there, and the woman who sold me the record previously wasn’t alone behind the counter. There was also an older hippie-looking guy: balding with long, stringy hair, paunchy, wearing an untucked button-down shirt. He didn’t exude the aloof superiority I had come to expect from dance-music record stores, so at some point I took the opportunity to mention I had a lot of success with the Arsenal 12” still on the shelf.

“Ah, where did you play it?” I told him I didn’t play it at a club, just a new year’s party. He sussed out immediately I wasn’t a “real” DJ, but his response seemed very charitable to me: “Sometimes those private parties are the best places to play.”

Fast forward a few months. My 12” collection continued to grow, as did my research into the history of dance music. Flush with discretionary income from my new job and single lifestyle, I walked into Dubspot Records and decided to get the David Mancuso Presents The Loft (Vol. 1) box set I had seen on the shelf previously, as well as Fela Kuti’s Zombie LP. (How’s that for an eclectic dance music store?)

The hippie guy behind the counter rang up the Fela Kuti album first, then the box set. “I hope you like this,” he said, tapping on the box set. “My card is inside.”

“Oh… your card?” I asked, confused.

“Yeah. I’m David Mancuso.”

“You’re David Mancuso,” I repeated. All this time, this unassuming man behind the counter at Dub Spot I was talking to was the David Mancuso. Before the publication of books like Love Saves the Day or Brewster & Braughton’s Last Night a DJ Saved My Life, I’d never even seen a picture of Mancuso. I wrapped up with some small talk, asking him if he still did the Loft. Not as much, he said, although he had a Thames River gig in London coming up. And then we finished up our transaction, and I left. My clueless brush with the dance music giant came with no embarrassment shown on his part, no condescension projected toward me.

I don’t know how many more times I went to Dub Spot, but I didn’t see Mancuso there before the store went out of business. After 9/11, the house-music economy that Rey and I tried to enter seemed to deflate; it was now the time of electroclash, tech-house, and the DFA Records sound, with the wide-ranging elements of old-school NYC house increasingly confined to “classics” events like Shelter.

I hope I never lose the gratitude of my encounter with Mancuso. In two brief exchanges, I observed the generosity of self, lack of ego, and commitment to the music over everything else — over DJ status, nightlife hierarchy, musical trends — that inspired the Loft and the very best in underground dance music. Rest in peace, gentle giant.

2 comments

Yago says:

Mar 4, 2018

I too met him there in 2001 after buying a box of records, only years later coming to understand the significance of the moment.

2018- I still play the music he popularized to his day and day dream of the bliss that was created on his dance floors

Thank you DAVID

Yago says:

Mar 4, 2018

And 19 years later, I still hold on to my 2 Dub spot T-Shirts-Red & white with the sweet Logo of Asian chick rockin Headphones.

Thank you for writing this. I too couldn’t find any material on the long lost store