20. Black Eyed Peas

Hate to say it, but “I gotta feeling” (oof, sorry) that the Black Eyed Peas have shaped the sound and BPM of American pop music more than anyone else in the last five years. Such influence would have been unfathomable back in 1998, when their debut album launched a hip hop trio from Los Angeles looking for a little of the native tongues-style credibility that the Jurassic 5 seemed to bogart — not to mention back in 1992, when will.i.am and apl.de.ap began their recording career as the Atban Klann (A Tribe Before A Nation) with an album on Eazy-E’s Ruthless Records.

With over a decade of indistinct rap and commercial failure behind them, the Peas’ crossover ambitions fell into place with the addition of female vocalist Fergie, their transition to mainstream R&B, and then will.i.am’s work behind the mixing desk for chart-toppers like Pussycat Dolls, Ciara and John Legend. These gave him access to the world of dance-music producers and DJs then preparing their seige upon American charts, which the Black Eyed Peas helped marshall with 2009’s “I Got A Feeling,” co-written and produced by French house producer David Guetta. The string of massive hits that followed helped to ratchet up the beat of R&B-flavored pop to oonce-oonce tempos, weaving in electro gimmicks and autotune inanity in catchy, often innovative mixes. If what was once recognizably “black” pop is now in retreat on American charts and mainstream dance floors before the dominance of EDM, the Peas deserve some credit/blame for that.

19. Pulp

The best band of the 1990s Britpop era — yeah, I said that — earned that distinction only after a long slog through obscurity. Jarvis Cocker formed Pulp with a pair of working-class Sheffield mates back in 1978, inspired by the DIY postpunk ethos. John Peel played their cassette on a 1981 broadcast, which boosted Cocker’s ego sufficiently to endure ten years of near-obscurity. Seriously reconsidering his options, Cocker enrolled at London’s St. Martin’s College with him mate, bassist Steve Mackey; this not only inspired the band’s greatest hit but (as Owen Hatherley argues) bookended the English era of art schools churning out working-class rock musicians. On return to Sheffield, Pulp released their third album in 1992 to only slightly more attention.

In hindsight, Pulp benefited from the Great English Loosening Up ushered in by the rave era. Not that Pulp made dancefloor bangers; their beats sounded rickety and two-bit, which only served to highlight the absurdities of a night on the town. But that subject matter was now their muse, with Cocker adopting a new element of humorous commentary and the band’s experience in crafting hooks finally producing chartable results. As Britpop uncritically celebrated the culture of the UK lad, the genre suddenly had its unlikely, bemused poet laureate. Pulp may never surpass the popularity they achieved headlining Glastonbury, but the dividends have paid off well: two more excellent albums and (a decade later) a much-needed reunion.

18. Aretha Franklin

The Queen of Soul was born into gospel royalty at the Detroit church where her father, the Reverend C.L. Franklin, preached. By age 14 she had recorded a gospel album with her sisters and become a musical polyglot, training in jazz piano and opera vocals as well. Sam Cooke’s secularization of gospel, the roots of soul music, was a particular revelation, and with some effort Aretha received her father’s blessing to pursue a pop career. When A&R man John Hammond brought her on to Columbia Records in 1960, Aretha’s ascent seemed assured…

Except that it never happened, thanks to the easy listening/pop vocals material that Columbia saddled her with. Aretha was seemingly grounded with Columbia for seven long years, during which time R&B and soul music exploded on independent labels like Motown and Stax. Within days of her contract’s expiration, Jerry Wexler signed her to Atlantic and flew her south to Muscle Shoals, Alabama, where Rick Hall’s Fame Studios had just replaced Stax as Atlantics southern studio of choice. A fortuitous set of circumstances ignited the career that should have been making waves years earlier. Aretha finally let her gospel voice loose before an appropriately “greasy” Muscle Shoals rhythm section (in actuality, an all-white studio ensemble) on her Atlantic debut, 1967’s I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You, and the Queen of Soul began her reign in earnest.

17. Fairport Convention

In 1967, this British six-piece was in thrall to the west coast sound, right down to Airplane’s dual male/female lead singers (Iain Matthews and Judy Dyble). Their folk-rock sound was a refreshing tonic for London’s psychedelic travelers, although it could still use refinement. Dyble was replaced by Sandy Denny, who brought a keening soprano, songwriting chops and. crucially, an intimate familiarity with traditional British folk songs. Evidence of the latter was mostly symbolic on the next two records, which nonetheless yielded standards like “Meet On The Ledge” and “Who Knows Where The Time Goes.” But as British rock got ‘deep’ and American rock went back to the country, the band’s greatest innovation lay before them.

From the songbook of British folklorist Cecil Sharp, the Fairports worked up versions of “Matty Groves,” “Tam Lin,” “Reynardine” and other traditional ballads in wholly new style: Denny’s voice evoked tales of old told in medieval castles while guitarist Richard Thompson and fiddler Dave Swarbrick took lancing, extended leads. 1969’s Liege & Lief became the blueprint for a genuinely original British folk-rock. A cohort of like-minded “traditional” groups followed in its wake, some featuring former Fairports (Steeleye Span, Strawbs Fotheringay, etc.), and soon British hippies were grooving to a (reimagined) indigenous traditional music that bypassed the proletarian folksong of Ewan MacColl. Fairport Convention lost a degree of adventurousness once Denny and Thompson left for solo careers, but the current band still hosts the annual Fairport’s Cropredy Convention to thousands of festivalgoers.

16. Radiohead

OK Computer had already raised Radiohead’s star pretty high. In a post-Cobain world, fans of alternative rock who were on the fence about contemporaneous UK developments (Britpop, trip hop, drum and bass) embraced this British group as their guide to a new future of rock. Of course, Radiohead was still, recognizably, a rock group, and that was always part of the deal. Indeed, with their ponderous compositions, Johnny Greenwood’s appealing guitar melodies, and Thom Yorke’s paranoid wail, they often suggested an alt-rock update of Roger Water-era Pink Floyd.

The next Radiohead album reneged on this deal, to the shock and dismay of many listeners. Perhaps fitting for an album released in the new millenium, not long after fears of a Y2K-induced global short-out had subsided, Kid A presented slice-up recordings, electronic rhythms, and minimal arrangements. In many places it sounded like half the band was missing, or maybe made redundant by the (ghosts in the) machines whose conversations listeners asked to eavesdrop on, with only the intermittent presence of Yorke’s voice offering a familiar assurance. Despite this all, or because of it, Kid A worked fantastically, reinventing Radiohead into the rock festival’s favorite experimental unit; all those listeners they drove away made it easier for the remaining fans to draw closer (and presumably have an easier time driving out of the parking lot afterward).

15. Elvis Presley

Traditionally the “day the music died” refers to the death of 1959 death of Buddy Holly, Richie Valens and the Big Bopper, but by 1960 the rest of rock’s original stars weren’t helping things, either. Jerry Lee Lewis sank his own career by marrying his 13-year-old cousin, Chuck Berry had run out of top 40 hits (and would be sentenced to three years in jail by 1962), and Carl Perkins and Johnny Cash had left rockabilly for country western. The return of Elvis Presley back from two years in the military was kind of a last chance for rock and roll, and his new album Elvis is Back! seemed to hold some promise, with guitarist Scotty Moore and drummer DJ Fontana (two-thirds of his famous rockabilly band) on board.

Things didn’t turn out that way, needless to say, as his manager Colonel Tom Parker focused Elvis’ career in the 1960s almost entirely on movies. The soundtracks were strewn with subpar material, and eventually the hits stopped coming. His 1968 television special for NBC “Elvis” (a.k.a. the ’68 Comeback Special) is generally thought to have halted his slide into cultural irrelevance. However, the fact that it was his first TV appearance since 1960 and, remarkably, his first live performance since 1961 underscores how much Elvis’ career had abandoned many of his strengths and, in a decade of rapid musical and social change, effectively made him a caricature to many in the new generation.

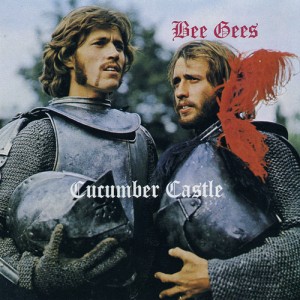

14. Bee Gees

Among its many virtues, Bob Stanley’s new music history tome Yeah Yeah Yeah: The Story of Modern Pop attests to the remarkable depth and singularity of the Bee Gees’ catalogue prior “Saturday Night Fever,” extending over two decades and 14 studio albums. The disco era may forever be associated with Barry Gibb’s hairy chest, leonine mane and bracing falsetto, which only makes the Bee Gees’ earlier music, particularly from the late 60s, all the more remarkable. As often as not, Robin Gibb was the voice of the Bee Gees’ back then, and the material tended toward mawkish balladry (1968’s “I Started a Joke”) and baroque concept pop (e.g., 1969’s Odessa). The band known as “the Bee Gees” was actually a malleable entity; at times the promo photos featured members other than Gibb brothers, and Robin even left the group for a spell.

The stars began aligning for the Bee Gees’ late 70s ubiquity as early as the decade’s beginning when manager Robert Stigwood began pushing Barry as the frontman. By 1973, the Brothers Gibb were recording in Miami and exploring the lush R&B sound then associated with the Philadelphia International Records label. 1975’s Main Course presented the sound that the Bee Gees would take to the top with the disco gallop of “Jive Talking” and the group’s first ever falsettos on “Nights on Broadway.” In 1977 Stigwood began producing a movie about the ascendant disco craze and, remarkably, only brought the Bee Gees in during post-production. No matter: the cultural association of group, film, and era would soon become irrevocable.

13. Marianne Faithfull

Marianne Faithfull was a countercultural icon in the late 60s for too many of the wrong reasons. She’s known to most as Mick Jagger’s first major girlfriend, the “girl in the fur rug” when police busted into Keith Richards’ home in 1966 and dragged the two Stones to court for drug possession. This image, as well as the one of the dissolute, broken-hearted girl on the short end of Jagger’s infidelities, unfortunately paints Faithfull as a passive victim, as in a way did her 60s fame as male fantasy (exploited in the 1968 film “Girl on a Motorcycle”). Yet Faithfull was also a creditable musician, recording one of the first Jagger-Richards compositions “As Tears Go By” a full year before the Stones did and co-writing Sticky Fingers’“Sister Morphine” (a legal battle finally compelled the Stones to give her credit in 1994).

The baggage of her notoriety overwhelmed Faithfull in the 1970s, when she fell into heroin and cocaine addiction and ended up living in a Chelsea squat as punk rock raged in London. Out of these circumstances came one of the great comeback albums in rock, 1979’s Broken English. Nominally a new wave album in sound and spirit, it presented a bloody but unbowed Faithfull singing in a now-cracked and lower voice. (“Female Tom Waits” is off the mark but points you in the right direction.) Since then, Faithfull has steadily released an uneven but always adventurous catalogue of albums that showcases her skill as an interpreter; she also continues to perform on film and stage as well. Although her health has been in doubt recently, her iconic strength and glamour will always endear her to fans as something along the lines (as Patsy and Edina in “Absolutely Fabulous” discovered in a hallucinatory vision) of God.

12. Talk Talk

At least for my musical generation, Talk Talk is the most compelling example of a group suddenly and wholly successfully pursuing a singular, emotionally powerful muse in defiance of record company expectations and in advance of everyone else. The London group began as a decent but generally overshadowed new wave group, one of those names you think of in the music trivia category of “bands who titled songs after themselves.” (Quick, think of others.) Singer Mark Hollis had a unique voice, thickly textured and odd in inflection, and the music registered as melancholy if energetic synth-pop — not bad at all, but not all that different from, say, China Crisis (who, remember, got Steely Dan’s Walter Becker to produce their second album!). They stuck it out through 1986, when new wave’s sell-by date was already a couple of years past, with the fetching “Life’s What You Make It” and then vanished to little public consternation.

In 1989 Talk Talk released Spirit of Eden with no publicity whatsoever, evidently a low priority for EMI Records and completely out of step with the British hype for shoegaze and the Stone Roses. The record was slow and rambling, punctuated by outbursts of dynamisms and emotion; arrangements and instrumentation were exquisite but ofered no signpost to their purpose or precedent; the music seemed as unintelligible as Hollis’ enunciation increasingly sounded. Three years later another album appeared, Laughing Stock, and was, needless to say, overshadowed by the media din surrounding My Bloody Valentine and grunge. This one seemed even quieter and more still, as signalled the fifteen or so seconds of barely audible amplifier hum that opens the album. Did anyone notice that Talk Talk had found a new record label at this point? Maybe by five to ten years later, as the celebration and revisiting of these two quiet milestones of “post-rock” continues apace.

11. Genesis

One of the most popular first act/second act rock groups of all time, although not the last one we’ll encounter in this list. A serious, literature group who secured a record deal through an alumnus of their posh public school, Genesis vied only with Yes as the quintessential progressive rock group of the early 1970s. With their lengthy compositions and clever time changes, they were pretentious and dull as sand, enlivened only by the theatrics and costumes of Peter Gabriel, which of course alienated him from the rest of the group. He left Genesis after their most interesting album (1974’s The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway) for a frankly better situation, and the child-actor-turned-virtuoso-drummer surprised everyone by stepping up and acquitting himself decently as a sensitive vocalist.

Jesus, it seemed like FOREVER (in truth, only three albums) before Genesis found their pop-rock muse — and all they had to show for it was 1978’s soft-rock nugget “Follow You Follow Me.” Then Phil Collins had an unexpected commercial smash with his 1981 commercial debut album ( that one with the quintessential air drum break), and suddenly Genesis were off to the races with dispeptic gurgle of “Mama” and the insufferable power balladry of “In Too Deep.” After that came more Phil Collins records, the best-forgotten Mike and the Mechanics, followed by new Genesis albums and reunion tours which, while spaced longer and longer apart, only reminded music snobs like myself how much of their lives had unavoidably been wasted upon Genesis’ dreary pop and snooze prog.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vRD49AFxJVINEXT:

10-1