In the town where I live, there’s been a lot of chatter over a recent NY Times article which reports how Brooklynites (an apparent synonym for NYC’s mobile, creative types) are descending upon the Hudson Valley area some 75 miles north of the city to live, visit, consume, and generally do their Brooklyn thing. Local businesses, restaurateurs and tourism bureaus have enthusiastically forwarded and tweeted this article, while locals cluck at the metropolitan hype surrounding the next big thing.

(A choice Facebook exchange about the article:

“Some nuggets of truth and infuriating stereotypes.”

“You’ve just described every lifestyle article the Times prints.“)

As an urban sociologist who has lived in the Hudson Valley for 12 years (which is chump change among my neighbors) and studied amenity-based urban economies for even longer, I thought I might weigh in on a few issues raised by the article and subsequent debate. If the topic today is a local one, I hope readers can appreciate how the dynamics I discuss extend much further than New York.

A FAMILIAR STORY?

Peter Applebome, the reporter on this article, is known to be a smart guy when it comes to deciphering the significance of regions and social landscapes. I haven’t read his 1996 book Dixie Rising: How the South is Shaping American Values, Politics and Culture, but it comes highly recommended. About midway through the Times article, Applebome hones in on a key set of underlying dynamics:

The migration north began with the weekender incursions in the ’80s and ’90s, gained a more urgent and permanent tone after 9/11, stumbled during the real estate bust and is now finding its way again. But, for all the images of upstate decay, the population of the Hudson Valley is growing more than twice as fast as that of the rest of the state — 5.8 percent over the past decade, compared with 2.1 percent for New York State and New York City. (While there are no universally accepted boundaries to the Hudson Valley, this reference includes the counties north of suburban Rockland and Westchester and south of the capital region: Putnam, Orange, Dutchess, Ulster, Columbia and Greene.)

Add in disparate institutions with some shared sensibilities — Bard, Vassarand SUNY New Paltz; the Culinary Institute of America and the sustainable agriculture Glynwood Institute; the New Age Omega Institute, Dia:Beacon, theStorm King Art Center, the green, hip and upscale Chronogram Magazine — you can posit a synergy that is gaining critical mass.

Some of the growth is an extension of suburban New York into Putnam and Orange Counties. The rest is an exurban phenomenon facilitated at least in part by new technology, the limitations of space and cost in the five boroughs and the natural search for something new.

These assessments are valid, if a little too narrow in their geography (a number of migrants have fled Westchester County and other outerlying NYC suburbs), and they point to the central structural shifts in NYC’s metropolitan economy that are driving the cultural and physical transformations in Hudson Valley life. However, it’s inunderstanding those transformations, particularly the cultural ones, that the article raises flags. Per journalistic convention, Applebome stokes the human-interest angle by drawing heavily on speculative assessments and generalizations made by his informants, who are divided between inquisitive, enthusiastic Brooklyn transplants…

THERE is a parlor game people sometimes play, comparing Hudson Valley towns with New York neighborhoods, said Sari Botton, a freelance writer in Rosendale.

For instance, Rhinebeck might be the Upper East Side, Woodstock the West Village, New Paltz the Upper West Side, Beacon the East Village, Rosendale and High Falls different parts of Williamsburg. Tivoli could be compared to Greenpoint, Hudson to Chelsea, Catskill to Bushwick, Kingston to a mix of Fort Greene and Carroll Gardens.

…and skeptical-to-embittered locals:

Not long ago, Hudson was notorious for drugs, prostitution and post-industrial torpor. Now, Warren Street, with its antique stores, galleries and hip restaurants, is a vision of the Hudson Valley reborn. And it was the scene of perhaps the last great battle between the old industrial Hudson Valley and the new one, when a coalition of interest groups came together to defeat a proposed coal-fired cement plant with a 40-story smokestack capable of producing two million tons of cement a year. Opponents said it would be an environmental disaster that would cut off access to the river and go against everything Hudson was becoming. They made an overwhelming case. But in the housing projects and poor neighborhoods just off Warren Street, strangers in the new landscape, it doesn’t seem so clear.

Sitting in a downtown park, Calvin Wilson Sr., 63, said it was nice to see the revival on Warren Street, but it didn’t offer much for him or for young people growing up in a town whose population is almost a third black and Latino, and in which one in five residents is living below the poverty level. “All those old factory jobs, they’ve all dried up,” Mr. Wilson said. “So, where those people going to work? Me, I wished they’d built that cement plant.”

The drama of a story familiar to NYC residents is further heightened by the article’s title (“Williamsburg on the Hudson”) and the title that appears at the top of your web browser when you load the article’s URL (“Hudson River Valley Draws Brooklynites”). Then there’s the language used to describe the transplants’ profiles. In the article, “artist,” “creative” and “scene” appear three times in their arts-based urban revitalization connotations. “Hip” also appears three times, four if you count this derivative:

Call it the Brooklynization of the Hudson Valley, the steady hipness creep with its locavore cuisine, its Williamsburgian bars, its Gyrotonic exercise, feng shuiconsultants and deep clay art therapy and, most of all, its recent arrivals from New York City.

Neither “hipster” or “scenester” appears once, but by now maybe you can see where this is going. The elements of an overdetermined discourse of Brooklyn’s gentrification — certainly one of the most important stories of NYC over the last 20 years, but one so accessible, so gut-level, so knee-jerk that it’s blinded many to the city’s more troubling roles in privatizing urban governance and triggering the economic downturn — have predictably surfaced. Not just in the article itself, but in the larger cultural context that this article reports and in fact epitomizes. Consider this paraphrasing from a provocatively titled piece, “Brooklyn Hipster Virus Spreads to Hudson Valley,” in a popular NYC blog:

In Hudson, a “coalition of interest groups” (translation: hipsters) successfully stopped a coal-fired cement plant from being built and harshing the idyllic vibe… Longtime local residents displaced by gentrifying scenester transplants?

SO WHERE ARE THE HUDSON VALLEY’S HIPSTERS?

Now, I confess not to being up on the latest trends for NYC hipsters might be, but I suspect that feng shui and $25 locavore entrées aren’t everyday fare for your twenty-something aficionado of witch house and lop-sided haircuts. Maybe this is all just semantics in regards to “hipster,” that increasingly derogatory and overused term used to label almost any connoisseur of au-courant tastes we don’t like. Still, it’s easy to lose sight of how the 20-something demographic, the age-bracket generally associated with the hipster, is the most important force behind “Brooklynization.”

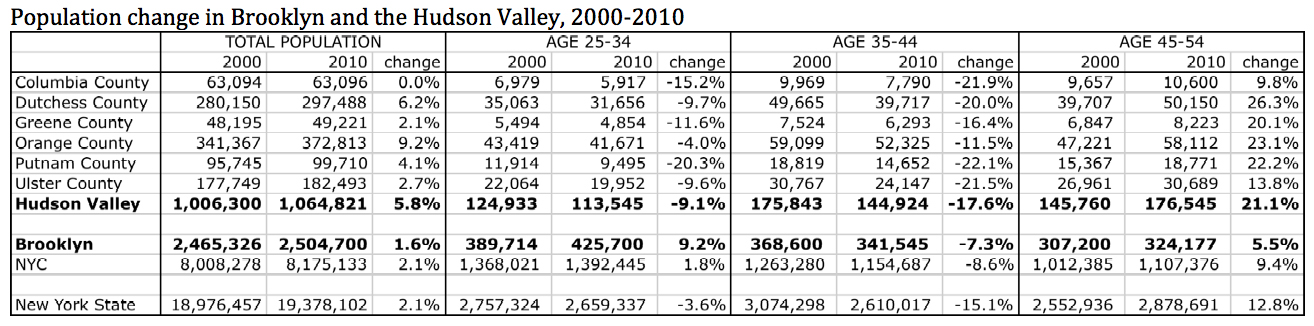

Census data from the last decade provide some supporting numbers (click on the table for a closer view). In the “total population” columns, you see the 5.8% and 2.1% growth that Applebome cites for the Hudson Valley and NYC, respectively. These are remarkable figures for a Rustbelt state; further upstate, New York has steadily bled population continually for well over the past decade.

Now notice the 25-34 age bracket, peak years for creative/enterpreneurial/DIY activities and a hipster lifestyle before thoughts turn for many to building relationships, homes and families. The 9.2% growth of this age bracket is the key demographic indicator for “Brooklynization”. The other NYC boroughs can hardly keep up with it, nor can the Hudson Valley, which has lost this age bracket by roughly the same percent of change.

Turn to the 35-44 age bracket, a key period of life for consolidating a career, buying a home and (at least in a prior era) building a family. Brooklyn thins out in this age bracket, but so does the Hudson Valley at even greater rates. (I see evidence of this in my hometown of Rhinebeck, where the number of kindergarten classrooms in the public school dropped from four to three last year.)

The pattern shifts when you get to the last age bracket here, age 45-54. Brooklyn’s population here has grown, albeit not as greatly as the rest of the city. (Is this a peak age bracket for buying Brooklyn brownstones?) Meanwhile, the Hudson Valley’s general growth really comes into focus with the 45-54 bracket. This isn’t simply the pattern of proportionate growth amidst absolute population decline (i.e., by this age people become less likely to move out) found further upstate. This is absolute, positive growth of a population who, we can confidently infer, comes from somewhere else—certainly NYC, but no doubt many other places as well.

THE HUDSON VALLEY QUALITY-OF-LIFE DISTRICT

Hence the one word I’d use to describe the cultural appeal of the Hudson Valley:sleepy. Five-and-dime stores and village business districts may be doing okay so far, especially when the farmers market’s in town, but they’re hardly support an energetic streetside scene of the kind we associate with Williamsburg. Restaurants may vie for choice downtown locations, but it’s not a make-or-break issue; their customers “eat the Hudson Valley” mostly via chefs’ pedigree (a number of Culinary Institute graduates don’t leave the area) and regional agriculture (a lot of squash), as filtered through not-just-New-York culinary/environmental principles (locavorism, CSA agriculture, etc.) — less via scenic views from their tableside window.

I’d argue the real amenity consumption in the Hudson Valley goes on in private spaces and natural solitude: the primary residences, vacation rentals and second homes where urbane residents and tourists enjoy the scenic idyll and a tranquil quality of life they can’t find in NYC, its suburbs or other hustling-and-bustling locations. A number of these residents commute back to NYC and environs for work, so that here they and their families can enjoy any number of local draws: more square footage for a home theater or art studio, good public schools, a winter that isn’t quite as harsh as it gets further upstate. Others simply make a routine of their weekend sojourn, as suggested by the noticeable fraction of NYC kids at my 5-year-old’s Saturday soccer practice.

Significantly, the second-homers and day-trippers don’t show up in the Census population figures. And no doubt a hipster segment ages 25-34 is visiting the art institutions, village downtowns, lakes and nature preserves. But so far, this group doesn’t live here, and they’re a difficult clientele to build a visitor-based business upon. In their local consumption patterns, they follow the lead of the older migrants and visitors, as witnessed on Warren Street in downtown Hudson. It has a handful of great stores selling used records, vintage clothing, antique curios, and other cool stuff, but most of the other stores sell carefully curated, high-priced antiques to affluent customers looking to furnish their homes or businesses. So for Williamsburg’s 20-something hipsters, a day on Warren Street is spent mostly browsing. Maybe browsing antiques in such an “unexpected” location can be fun, but it also provides an education for a future of domestic furnishing and tasteful connoisseurship when they’re a little older and a little more affluent.

To return to my larger point, the newcomers whose money and tastes are transforming the Hudson Valley aren’t really the hipsters that bloggers love to deride. For every middle-aged photographer or Etsy vendor with blue hair, there’s probably 50 lawyers, writers, architects, and other creative professionals living much more conventionally. But maybe Brooklyn’s hipsters include these future middle-aged quality-of-life migrants. The Hudson Valley has to be understood not as just offering a particular kind of quality-of-life niche, to be contrasted with other metropolitan getaways like the Hamptons or the Jersey Shore, but also supporting an age-specific pursuit.

Furthermore, the sociologist in me contends that these quality-of-life preferences aren’t just random; they don’t simply activate once people reach a certain age. No, it’s the metropolitan rat-race of “everyone for themselves” and “winner takes all” — all the occupational autonomy, best housing, private-school spaces, etc. — that structures these pursuits. (By contrast, consider the IBM “company men” [and women] who were historically based in the Hudson Valley and still live around in significant numbers: locavorism and feng shu aren’t their calling cards.) The corollary is that the Hudson Valley’s local qualities and opportunities aren’t intrinsically attractive, no matter what local boosters and Brooklyn enthusiasts might say. Rather, these become more attractive as NYC’s economy drives change throughout the metropolis, differentiating and revalorizing its cultural landscape by class, race, ideological disposition, and age.

There’s so much more to say about how local nuances and conflicts manifest along these divides. For the time being, I’m going to punt on those. In my next post, I’ll discuss the music that accompanies the changes in the Hudson Valley.