The exhibition of Native Americans at the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893 was not unique. The exhibitions, designed by some of the leading anthropologists of the day, would not have been far from home in any natural history or ethnographic museum. In fact, many of the components that made up the Native American exhibits ended up the Chicago Field Museum, and eventually other institutions through exchanges.

In designing the Native American villages of the Exposition, anthropologists focused on presenting visitors with an authentic experience. To them, this meant recreating pre-Columbian Native cultures. The result of this approach was the portrayal of Native American people and cultures as exotic, primitive, and disappearing, in keeping with predominant theories of societal evolution at the time. The same sentiments were rampant in museums, perhaps unsurprisingly since many of the anthropologists who worked on the Exposition had successful careers in that field.

Given the close relationship between the Exposition and museums, it should not be surprising that many of the pieces used in the Native American villages ended up in their collections. It is unclear, however, whether the Native communities who made props and from whom materials were collected were aware that their property was destined not to be returned.

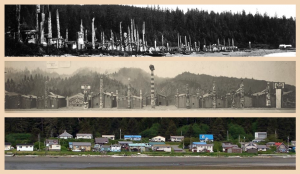

In 1892, seventeen Haida artists (see below) were commissioned to create a replica of Skidegate village in British Columbia as it looked in 1864. The model consisted of 27 houses (all but three of which had frontal poles), two grave houses, and 17 free-standing poles. After the Exposition, the model was placed in the Field Museum of Natural History, where 10 of the house models and 22 of the poles have remained. Nineteen houses and 21 poles were exchanged or given away to other institutions, and of those 13 houses and 13 poles are unaccounted for.

In 2001, the Haida people of Skidegate, B.C. and the Haida Gwaii Museum at Qay’llnagaay collaborated with the Burke Museum (Seattle, WA) and the Field Museum to plan an exhibit of the collection at the Qay’llnagaay Heritage Centre and other venues. Despite the setting that they were created for, the model village was capable of being repurposed to tell a self-representational narrative.

The repatriation movement seeks to return not only objects, but also knowledge and representation. When paired with a Native perspective, even objects created for such an imperial purpose as the Columbian Exposition can be used to tell a decolonized narrative.

Many pieces from the Columbian Exposition remain in the Field Museum and similar institutions to this day. Repatriation of these objects would allow for them to be used by the communities by which they were made to tell a version of history that others often choose to ignore, perpetuating the violence of that era. Such action would be a step toward removing the veil of secrecy placed over the unethical history of the treatment of Native Americans by museums and similar institutions that continues to the present.

The Haida artists: Adam Brown, Peter Brown, John Cross, George Dickson, William Dickson, Daniel Ellguwuus (‘Iljuwaas), Phillip Jackson, Joshua (Kinna-jesser), Moses McKay, Phillip Pearson, John Robson (Gyaawhllns), Amos Russ, David Shakespeare (Skilduunaas), Peter Smith, Tom Stevens (Tl’aajaang quuna), George L. Young, and Zacherias Nicholas.

Kwakwaka’wakw image source and suggested reading #1: http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Popular_Science_Monthly/Volume_43/September_1893/Anthropology_at_the_World’s_Fair

Suggested Reading #2 (discusses Haida repatriation efforts): http://www.repatriation.ca/index.html

Skidegate Village image source: http://www.burkemuseum.org/static/bhc/haida_models/exhibits/

Brooklyn Museum model image source: http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/129925/Model_of_House_of_Contentment