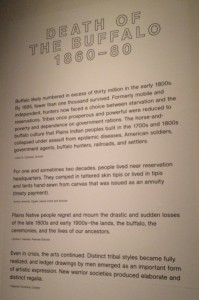

The destruction of memory has disastrous implcations. Though it may seem incomprehensible that groups such as ISIS in Iraq, and Assad in Syria, focus so intently on destroying museums, they use the destruction of cultural objects as a means to erase cultural memory. When, if cultural history and memory are at stake, is it important to protect these sites and artifacts? At what cost should people fight against tyranny to protect cultural heritage?

In Dr. Richard M. Leventhal’s lecture, “Killing Culture: Heritage Destruction in the Syria and Iraq Conflicts,” he discussed the importance of cultural heritage, how it is being destroyed by groups such as ISIS and Assad, and what should be done about it. Beginning his lecture with videos of ISIS destroying sculptures in the Mosul Museum and the ancient city of Hatra, Iraq, Dr. Leventhal emphasized the very real and imminent destruction of heritage in Iraq and Syria. As I watched this graphic destruction, I wondered about the intent of individuals who are a part of ISIS. Clearly, destroying objects in the Mosul Museum was a project designed to garner a reaction (as a video of the act was created by ISIS and was posted online). The destruction was personal – individual men and women hacking away at ancient sculptures.

Image Source

Compiled Video Footage of ISIS in the Mosul Museum

When a state and its leaders are so determined to destroy, how can we protect heritage? When asked by curators at the Libyan National Museum how they can protect the objects in their museum from threats of destruction, Dr. Leventhal advised that they hide objects in their homes or put them in the ocean. He advocates the importance of protecting cultural heritage. Because once these world treasures are demolished, they are permanently lost, Dr. Leventhal, and a team from the Penn Cultural Heritage Center (CHC), are doing all they can to protect and safeguard objects and sites of cultural heritage.

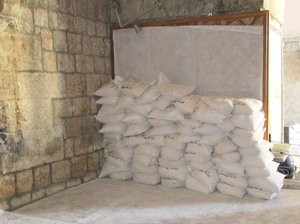

For Image Source and Further Information

With the Safeguarding the Heritage of Syria and Iraq Project (SHOSHI), Dr. Leventhal and the Penn CHC are working to protect sites in Syria from attack. They work to catalogue objects, complete training workshops for a Syrian Heritage Task Force, and lead projects to protect cultural heritage sites. Beginning with a project to protect the Ma’arra Mosaic Museum with a careful layer of tyvek and sandbags (a technique used in WWI and WWII), the team at Penn and its collaborators on the ground in Syria hope to guard heritage sites against destruction. There are many brave men and women in Syria and Iraq working to preserve their culture through the conservation of these heritage sites.

For Further Reading:

UNESCO

Penn Cultural Heritage Center

The Penn Museum

Philly City Paper

New York Times

NPR