Throughout this course we have argued that objects should be returned to their rightful owners through repatriation. I aim to complicate this with the question, who owns antiquity? When civilizations lived hundreds or thousands of years ago, who inherits their legacy and heritage? With a global population that is widely dispersed between multi-ethnic nations, it is hard to define any kind of pure cultural heritage. Who owns the past? Gillman queried if national heritage reflects the makeup of current inhabitants of a state or past groups that occupied that same space. Current nation-states do not reflect the geographical makeup of the past. How do we account for this when considering ownership of antiquity? How does this affect repatriation?

Symbolism from antiquity can be found all over the globe. The Roman symbol of the fasces can be found throughout United States Government buildings, including many locations in the U.S. House of Representatives. Does the United States have a right to use this Roman symbol? The United States uses symbols like these from antiquity to ground its own legitimacy as a western nation. As people of Roman descent now live all over the world, who owns Roman heritage? If Italy does, antiquity is limited by geographical boundaries that may not reflect the widespread communities who claim Roman ancestry.

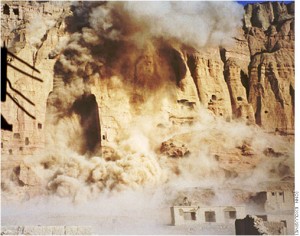

With physical artifacts from antiquity, this discussion of ownership is incredibly relevant. Changing nation-state configurations today affect ownership of antiquity that can be especially detrimental in current cases such as the destruction of cultural heritage by ISIS and the Assad regime. The Taliban, as leaders of the state of Afghanistan used its authority to destroy the Bamiyan Buddhas. These nations have used their power to control heritage. Yet this is no new trend in history – throughout time nations have destroyed objects that would now be considered important to cultural heritage. Antiquity is used as a political tool for power by nations.

James Cuno argues that national cultural-property laws “ are not intended to protect the world’s ancient heritage…they are used to legitimize modern governments’ claims as heirs to an ancient past.” Nations can determine their own laws and what they wish to do with their antiquities. UNESCO has attempted to mediate this by the creation of World Heritage sites that are supposed to be respected as international sites of heritage. How, as an international community, can strive to better value and respect antiquity across national boundary lines?

Recommended and Referenced:

James Cuno – “Antiquity Belongs to the World”

Peter Lindsay – “Can We Own the Past?”

Gillman. The Idea of Cultural Heritage, 2010.

UNESCO World Heritage

Information on fasces and fasces image source

Wikipedia Bamiyan Buddhas image source

Amy Gazin-Schwartz -“What the Islamic State’s Destruction of Antiquities Means to Archaeologists”