Jemima Pierre’s speech at Vanderbilt University in 2013 begins by tracing the term “diaspora,” one of the two primary topics of the panel’s discussion that evening. The originally Western term (Greek in origin) has been applied to many shifts of group identities in the globalized lens of history. However, as Pierre points out, since the so called “British Cultural Incursion” over the last 20 years, there has been a tendency (by a significant portion of scholars) in theoretical discussions of African diaspora to conceive of all the dispersed cultures through the lens of syncretism.

The minimization of Africa as a source of culture for contemporary Black people follows from the assertion of syncretism amongst cultures of the diaspora, which is problematic and reeks of British attempts at some neocolonial hegemony of African history. Additionally, the assumption of syncretism between post-diaspora peoples is reminiscent of the perception of Native American cultures as a monolith since the colonization of North America.

Another interesting point in this comparison comes when introducing the term “homeland” into the discussion of African diaspora and post-colonial Native American cultures. As Pierre points out, there has been a tendency to label Africa as the homeland of the past without granting this “mother culture” much in terms of considering the role it plays in a continued dialogue across the Atlantic Ocean. It is this “either/or” mentality which has also pervaded outsider (non-Native) concepts of Native American identity.

In Pierre’s discussion of the rampant generalization of diverse, dispersed Black cultures, we see many more points of continuity to Native American cultures. The tendency by anthropologists and historians (as she terms it) to simply document “the Blacks over there,” resonates strongly with the ethnographic lens through which many Native cultures have been viewed and subsequently documented — cemented in text, seeping into the national consciousness and concepts of Native peoples.

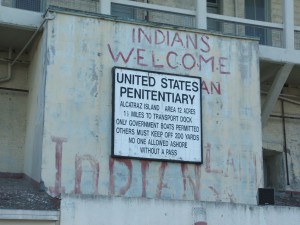

Another overlap occurs when Pierre laments the economic hegemony of European forces in Africa which still continue to this day, crippling many nation-states’ ability to economically flourish and of course threatening sovereignty. The current state of the majority of Native American reservations in the US speaks volumes, each one its own living testament to the economic, cultural, and political consequence of many histories of violence and colonial incursion.

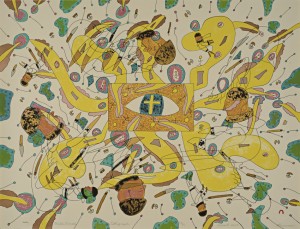

What should we glean from these many similarities? Instead of taking them to mean that cultures of the African diaspora and Native American peoples are inherently similar, perhaps we should look at the root of these many commonalities: colonialism. The overlapping challenges experienced trace their roots to wounds delivered by the same sword. It is through this commonality that, as in the case of the pan-Indian movement of Native rights, these very different groups could come together to fight against a common enemy, buoying one another with a unified activism.

additional resources: an interview with Pierre and her notes from a lecture in Virginia