In our class readings and discussions this week, we have examined some of the motivations and ethics of collectors collecting their collections. As someone planning on working in an art museum, I can certainly empathize with the frustration of knowing that countless treasures are tucked away in private collections. However, I wanted to take the time to examine how grounded that frustration truly is.

Take the museum institution closest to home: the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center. The Loeb touts itself as a teaching museum. Indeed, Matthew Vassar’s founding vision of the college began with an art museum in Main. Access to art was a fundamental part of the education Vassar provided. Flash-forward about 150 years later and the art museum has moved to a new building with thousands of objects. Many may see this massive collection as a boon to the school, as more tools with which to teach. But with a collection so huge and an exhibition space so limited, how many objects have never been displayed?

While it is true that Vassar students can set up appointments to go down to storage, they must know what it is they wish to see and, more importantly, know that this service is available to them. In the case of the latter, I would say the majority do not. The Loeb does provide an online database of its (over 19,000) objects, however it is tragically incomplete. In terms of real access by the students of Vassar or the public of Poughkeepsie, how different is the vast array of stored items in the Loeb from a private collection?

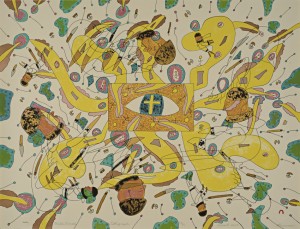

In line with questioning the assumption that museum acquisition of an object implies its availability to the public, we should also reexamine the perception held of the collector as some jealous hoarder of objects. In the case of the Loeb, collectors have been a major part of the museum’s growth. For example, were it not for collectors like Edd Guarino, the museum would have an abysmally small range of Native American art*. Guarino has donated and loaned a plethora of art objects from his private collection to the Loeb over the past decade. He has also been eager to share the wealth of knowledge provided by his collection with the wider public of the internet. Along with a handful of other collectors, Guarino writes a blog for King Galleries, featuring high quality images and art historical analyses of a large variety of privately owned Native American art.

When I worked with Guarino in 2013, his passion for educating others and sharing his collection was palpable. The experience taught me that the collector was not inherently a miser of beauty and knowledge. Rather, this collector wanted nothing more than to be surrounded by the objects he loved the most and to spread that love around. Certainly, Guarino should not be taken as the representative for all collectors, but his is a laudable legacy.

*It should be noted that, despite Guarino’s donations, no Native American objects are currently on display in the Loeb.

See also: the King Galleries “Collector’s Corner,” the website for an exhibit which was entirely comprised of objects from Guarino, the FLLAC database, and image source and information on Wild World

As a collector, over the years I have learned that there are many different types of collectors who who collect for a wide variety of reasons. This fact alone could be the basis for an article. Thank you for your kind words regarding my donations and loan. I have donated many works of Native art to the Loeb because it was sadly lacking in this area. If one is going to tell the complete story of World art or even just American art then art produced by Native artists cannot be omitted. In spite of my donations and that of other collectors, Native art is rarely on view at the Loeb. I have yet to get a satisfactory answer as to why this is so. The most I’ve gotten is “There are many works of art competing for very limited space.” Such a response is little more than spin.