When I entered The Plains Indians: Artists of Earth and Sky at the Metropolitan Museum this March, I was prepared to be dissatisfied. What I found instead was an exhibit too complex to have such a black and white reaction to. While I left the exhibit having greatly enjoyed it, I felt that there were subtle mistakes made and opportunities missed that may be symptomatic of larger issues in play, and would like to take this space to examine those.

The first example I would like to focus on is that of a an object in the second case the visitor encounters: an “ancient” buffalo effigy dating from 1600-1800 CE. Would anyone think to call a painting by Dutch artist Rembrandt (1606-1669) “ancient”? The idea seems laughable, yet, here in front of me was a piece of the same vintage being ascribed that loaded term.

A quick Google search of “ancient” turns up this definition: “belonging to the very distant past and no longer in existence. Synonyms: of long ago, early, prehistoric, primeval, primordial, primitive” (emphasis added). This description is problematic not only because it is inaccurate, but mainly because it reinforces dangerous language and stereotypes used against Native Americans, and Native people everywhere, to this day. Such language perpetuates harmful representations and tropes, and its use in this environment allows visitors to pass through the exhibit without having their previous perceptions challenged.

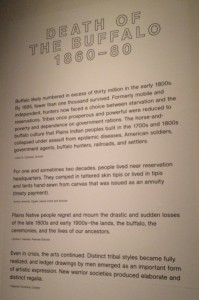

Another possible teaching moment is passed up. Beginning the section “Death of the Buffalo 1860-80” is a block of quotes from four of the exhibit’s most prevalent voices: Emma I. Hansen, Pawnee scholar, Arthur Amiotte, Oglala Lakota artist and scholar, Gaylord Torrence, curator of the exhibit, and Colin G. Calloway, scholar. What seemed to be an opportune moment to discuss the systematic slaughter of buffalo by the U.S. government and army (see article by Adrian Jawort) was passed without very explicit mention. The following quote comes closest to such a discussion:

“The horse-and-buffalo culture that Plains Indian peoples built in the 1700s and 1800s collapsed under assault from epidemic diseases, American soldiers, government agents, buffalo hunters, railroads, and settlers.”

– Colin G. Calloway, Scholar

In the same space it would have been possible to include explicit mention to the intentionality of buffalo extermination and its role in the genocide of the Plains Indians. This politicization, it seems, was decided against.

Photo by the author

The reviews of The Plains Indians have been mostly positive. It is for this reason that I have focused on negative aspects, in order to provide a more critical take. The exhibit is not without virtues. The descriptions, for the most part, go a good job of weaving together ethnographic details with artistic analysis, crediting and providing a picture of the artist where possible. The final section of the exhibit, “Reservations and Urban Life 1910-65,” showcases works by contemporary Native artists whose work has often been left out of museums, art and anthropology alike. However, at a time when the roles of museums and their relationship to Native peoples are changing, I believe it is important to analyze even the most acclaimed exhibits with a critical eye.

References and Further Reading, Listening, and Viewing:

Catalogue of Exhibition Objects

Image Source: