By Genevieve Lenoir (gelenoir@vassar.edu)

Well, after expending a great deal of energy trying to figure out how I was going to live up to the absurdly high standards set by Andrea in her post last week, I finally decided to just write about something I enjoyed and let the rest flow from there. One of the topics I’ve been interested in from a theoretical standpoint, and one which I’ve previously explored in a linguistics class, is the nature of artificial intelligence. Out of curiosity, I Googled “robot language” and immediately got this interesting result:

“ROILA is a spoken language for robots. It is constructed to make it easy for humans to learn, but also easy for the robots to understand. ROILA is optimized for the robots’ automatic speech recognition and understanding.”

According to the website, ROILA is an artificial language developed by a team in the Netherlands to make it easier for humans to communicate with robots. Robots have difficulty understanding natural speech — speech recognition technology is not yet developed enough to be effective, so misunderstandings between robots and people are common. Some people believe it is impossible for speech recognition technology to ever reach the level of human speech. To bypass these technical limitations, ROILA was compiled using simple grammar and phonemes that occur in a broad range of natural languages and have no irregularities, with a dictionary of words which are phonetically distinct from each other in order to divert the chances of mishearing a word. It is supposed to be easy for humans to learn, and the ROILA team offers free courses to teach humans the ROILA language (hosted on Moodle, funnily enough).

ROILA words are generated by a scalable genetic algorithm that produces words which are deemed to have the least amount of confusion between them. Definitions are taken from Basic English, a form of English developed by Charles Ogden in 1930 which contains only 800 words. The grammar is basic and contains no exceptions in grammar or syntax. It follows subject-verb-object form. I did notice that the language contains four pronouns: I, you, he, and she, and I thought it was very silly of them to use gendered pronouns in a language designed for communication between animate and inanimate objects. Just something I found interesting.

Here, NPR’s Morning Edition takes a quick look at ROILA:

Morning Edition

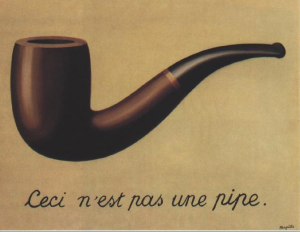

Robots have been undergoing intense coerced evolution since the time of the first simple mechanical device. As humans invest more and more time and energy into elevating mechanical/electrical inputs to the eventual goal of total human-like sentience, it evokes a great number of questions. Deacon states quite clearly that “Even under these loosened criteria, there are no simple languages used among other species, though there are many other equally or more complicated modes of communication…For the vast majority of species in the vast majority of contexts, even simple language just doesn’t compute” (41). Language is an intrinsically human creation, limited to Homo sapiens by our biology and our development. With that said, do we believe that robots — as a creation of human intelligence — are able to make use of our forms of communication? Robots are not like animals; it’s not that they have simple brains, it’s that they don’t have brains at all! If I’ve learned nothing else in this class, it’s that language and the way language functions in human cognition is vastly more complex than “words = names for things” and grammar and even the pragmatics of social situations. But robots are built by us, and to function they must work within the parameters of human understanding, which of course is heavily language-based. A robot which can use language, either recognizing it or replicating it, is doing something fundamentally different than a dog is when it interprets your commands. And, then, at the end a robot is just made of a bunch of circuits and signals. Some robots can “learn”, adding new functions as they interact depending on their programming. Some robots have been taught to react to facial expressions or tone of voice. Do we say that these robots have language skills on par with human beings?

Possibly my favorite part of the Deacon reading was when he addressed the problem of understanding. “Isn’t any family dog able to learn to respond to many spoken commands? Doesn’t my dog understand the word ‘come’ if he obeys this command?…Not exactly. We think we have a pretty good idea of what it means for a dog to ‘understand’ a command like ‘Stay!’ but are a dog’s understanding and a person’s understanding the same? Or is there some fundamental difference between the way my dog and I understand the same spoken sounds? Common sense psychology has provided terms for this difference. We say the dog has learned the command ‘by rote’, whereas we ‘understand’ it.” I would like to turn his sequence of questions to my own purposes:

Does a robot “understand” the language of its operators? Can a series of ones and zeroes accurately map a system like the inside of the human brain? What does it mean for a robot to use language?

Like with Deacon’s discussion of animals in myth and fiction, robots have often been romanticized in popular culture. We would all love to believe that computers will someday reach the point where they can act and behave just like us, smarter or stronger or more polite, but essentially human in every way that matters. Perhaps we believe that if robots can become human-like, if they can show some glimmer of a human soul, then humans, ourselves little more than a collection of biological functions and neurological pathways, will no longer need to doubt the nature of our own.