Shipwrecks have been heralded as time capsules in the ocean due to the complete nature of the artifacts they contain at the time that they sink, but shipwrecks and encrustations can be examined at a level even beyond the artifacts themselves. Ships, when they set sail, contain everything the passengers believe is essential to life for an extended amount of time. With this in mind, shipwrecks can provide insight into historical cultural materiality and, because the passengers and the crew on board will come from different classes, social hierarchies.

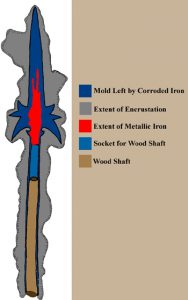

When artifacts that sank aboard a shipwreck are left in salt water for extended amounts of time, especially in warmer ocean temperatures, they often become covered with what is termed encrustation: a thick conglomeration of “calcium carbonate, magnesium hydroxide, metal corrosion products, sand, clay, and various forms of marine life such as shells, coral, barnacles, and plant life” (Hamilton 1997). While it may seem as though this encrustation is preventing the examination and analysis of the artifact within, the sediments themselves often contain a treasure trove of archaeological information. In fact, encrustations can indefinitely preserve impressions of objects that have dissolved which can be used as molds to recreate the objects (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A drawing made of an encrustation of a partisan found at the site of the Belle in Matagorda Bay, Texas. Not only was it possible to determine the original composite materials, but a cast of the blade was created using the impression left in the encrustation (Conservation Research Laboratory Texas A&M University; Composite Wood)

While it may seem as though encrustations destroy archaeological evidence, what they may dissolve is often made up for by the wide variety of information they provide. In addition to creating imprints that can be recreated, the encrustations preserve objects that would otherwise be destroyed in oceanic environments such as potsherds, fragments of cloth, and seeds and insects. Furthermore, each encrustation alone can contain an abundance of individual artifacts and ecofacts. In the case of the encrustation found aboard the San Esteban off of Padre Island, Texas (Figure 2) the encrustations of large iron objects like anchors each contained hundreds of smaller artifacts and ecofacts like bolts, coins, plants, and shell debris.

Figure 2. Various stages of extraction of the artifacts in an enunciation from the San Esteban, beginning with an x-ray to locate the objects within the conglomerate (Arnold 1980).

Another unique advantage of encrustations is that they hold a timeline of archaeological information. In a similar manner to geological stratification, exterior layers of encrustations will have formed more recently than interior layers. The ecofacts that inevitably become a part of the conglomerations can provide insight into ocean ecology based on the conditions in which living organisms can survive. With encrustations providing a geological timescale, not only can the information be used to date artifacts within the concretions but there is also the potential to learn about changes in ocean ecology over time and use trends in that data to predict future ecological conditions.

Reference List:

Arnold, J. Barto.

1980 Shipwrecks in the Wake of Columbus. Electronic document, https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/d70c/3a265da998dbfd37795bede31b1608b8b05b.pdf, accessed September 14, 2018.

Conservation Research Laboratory Texas A&M University

Overview of Conservation in Archaeology; Basic Archaeological Conservation Procedures. Electronic document, http://nautarch.tamu.edu/CRL/conservationmanual/File1.htm#Basic%20References, accessed September 14, 2018.

Conservation Research Laboratory Texas A&M University

Composite Wood / Iron Objects: Pole Arms and Partisans; La Salle Shipwreck Project Texas Historical Commission. Electronic document, http://nautarch.tamu.edu/CRL/Report2/polearm.htm, accessed September 14, 2018.

Hamilton, Donny L.

1997 Basic Methods of Conserving Underwater Archaeological Material Culture. Electronic document, http://nautarch.tamu.edu/class/606/UA_%20Conserv.pdf, accessed September 14, 2018.

Johnston, Grahame.

2018 Conservators of Underwater Archaeology. Electronic document, http://www.archaeologyexpert.co.uk/conservatorsofunderwaterarchaeology.html, accessed September 14, 2018.

Renfrew, Colin and Paul Bahn

2010 Archaeology Essentials. 2nd edition. Thames & Hudson, New York.

U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment

1987 Technologies for Survey, Identification, Navigation, Excavation, Documentation, Restoration, and Conservation. In Technologies for Underwater Archaeology and Maritime Preservation. Electronic document, https://www.princeton.edu/~ota/disk2/1987/8726/8726.PDF, accessed September 14, 2018.

Additional Content for Interested Readers:

Arnold, J. Barto and Melinda Arceneaux Wickman

1980 PADRE ISLAND SPANISH SHIPWRECKS OF 1554. Electronic document, https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/etpfe, accessed September 14, 2018.

Adovasio, J. M. and C. Andrew Hemmings

2013 Underwater Archaeological Excavation Techniques. Electronic document, https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/explorations/12newworld/background/underarch/underarch.html, accessed September 14, 2018.

I wanted to know if you could speak more about varying strategies underwater archaeologists may use versus those that would be used by land archaeologists. You say that underwater shipwrecks, particularly as points of transit and movement where people are packed for a journey, provide nice insights to class and hierarchy. When the ship initially sinks, if items are thrown about, eventually becoming ecofacts, how can we attribute ownership to these items? Poor people own nice things, and if one were traveling to live in a new place, chances are they would take whatever is valuable with them. In archaeology, the location of an object is just as important as what the object is itself. How do the archaeologists account for these taphonomic shifts, movements of things after their initial deposit? How do they account for currents in the water moving artifacts about?

In general, many of the techniques used by underwater archaeologists are very similar to those used in archaeology on land. The general tools of the trade (such as tape measures, trowels, and other hand tools) are used in both types of archaeology, but the two do vary in techniques of excavation is used. In underwater archeology, instead of shoveling dirt, a large dredge engine is used that pumps hundreds of gallons of water per minute to suck the sediments off the floor of the ocean (Adovasio & Hemmings 2013). The other major difference between marine archaeology and land archaeology is in the conservation. If artifacts that have been underwater for extended periods of time are to be displayed ex-situ (outside of the original site) it requires the object be treated by chemical reactions to preserve it before chemical reactions with oxygen disintegrate the artifact (Conservation Research Laboratory Texas A&M University).

In terms of attributing ownership, with my research I have found generally little information on how (or if) artifacts found are attributed to individual people once they are discovered at a shipwreck. It is true that sometimes “tax, ownership, mining, shipping, or other types of identification [are] stamped or marked on individual artifacts, provid[ing] additional leads” but beyond that, any attributing of artifacts is often done using archival documents (Hamilton 1997). When I spoke of artifacts being able to show social hierarchies I meant it (and I believe many of the articles I found which spoke of this phenomenon) more in the general sense of being able to look at the artifacts as all being attributed to the same relative time (as opposed to archaeological sites on land which can hold the records of hundreds of thousands of years). Because all of the artifacts will have been used or valued at the time of the ship sinking it allows for cultural materiality to be looked at. In addition, if the name and date of the shipwreck are known the artifacts can be cross-referenced with what is already known about maritime travel during the time period of the wreck to see if the passengers would be people of a higher class traveling for pleasure versus people traveling for religious purposes, or many other reasons. If this is known then the artifacts can be attributed to general classes of people as opposed to the individual.

For the location of underwater artifacts, it is true that they are often scattered due to environmental factors. This is often the case in shallow water wrecks, and it has even been suggested by some underwater archeologists that these sights are not worth the time and money of investigation because of a lack of coherent information (O’Shea 2002). In actuality, these sites, while they may not have the acclaimed “time capsule” nature of other underwater shipwrecks, are more palimpsests of time in a similar fashion to land archeological sites that contain evidence of thousands of years of life. Additionally, it is a necessary factor in underwater archaeology to not only have knowledge of the artifacts that are being looked at, but also to have a knowledge of environmental and other factors such as “storms, waves, woodworm, looters, or reef formation” (O’Shea 2002). With this knowledge in hand, it is possible for archaeologists to attribute artifacts that may not be immediately next to a shipwreck as part of the wreckage.

Reference List:

Adovasio, J. M. and C. Andrew Hemmings

2013 Underwater Archaeological Excavation Techniques. Electronic document, https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/explorations/12newworld/background/underarch/underarch.html, accessed October 23, 2018.

Conservation Research Laboratory Texas A&M University

Overview of Conservation in Archaeology; Basic Archaeological Conservation Procedures. Electronic document, http://nautarch.tamu.edu/CRL/conservationmanual/File1.htm#Basic%20References, accessed September 14, 2018.

Hamilton, Donny L.

1997 Basic Methods of Conserving Underwater Archaeological Material Culture. Electronic document, http://nautarch.tamu.edu/class/606/UA_%20Conserv.pdf, accessed October 23, 2018.

O’Shea. John M.

2002 The archaeology of scattered wreck-sites: formation processes and shallow water archaeology in western Lake Huron. Electronic document, https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/lakehuron-arch/wp-content/uploads/sites/59/2014/05/OShea-2002-The-archaeology-of-scattered-wreck-sites.pdf, accessed October 23, 2018.

Additional Content for Interested Readers:

(Statistics on Underwater Sites):

Demetriou, Anna.

2017 Management of Ancient Shipwrecks: the case of Cyprus. Electronic document, http://honorfrostfoundation.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Anna-Demetriou-Management-of-Ancient-Shipwrecks-2017.pdf, accessed October 23, 2018.