In the 1930s, a puzzling discovery came about in a siege mine at the city known as Dura-Europos in Syria. This city was controlled and run by the Romans as a military base backed by the Euphrates River, only until the powerful and overwhelming Sasanian Persian Empire made a push for the city. The Persians, however, did not go about this raid in a traditional way by any means.

The Romans had established a large garrison to protect the city from any foreign invaders. Persian forces had recognized this, so they designed a mine to be dug underneath the city wall in an effort to collapse it. Romans soon became aware of this and dug out a counter-mine, which ultimately led to the death of 19 Roman soldiers and one lone Persian.

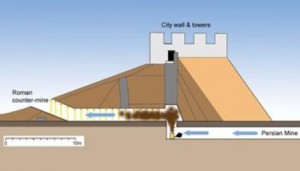

Diagram that shows the Persian mine designed to collapse Dura-Europo’s city wall, the Roman countermine which intended to stop them, and the possible location in which the Persians began to use the Chemical warfare against the Roman defense

Now how did the Persians manage to take down 19 Roman soldiers in such a tiny space? As the two different tunnels connected, the Persians had put together a form of chemical warfare, which to my surprise has been around for a significant period of time. Stephanie Pappas writes, “One of the earliest examples was a battle in 189 B.C., when Greeks burnt chicken feathers and used bellows to blow the smoke into Roman invaders’ siege tunnels.” The Persians used a chimney effect to gas out the Roman soldiers as the two mines met. Recent excavations revealed bitumen and sulphur crystal remains that provide evidence that those crystals were burned in order to create choking gases. The soldiers that were discovered were found stacked on top of each other to form a human wall for the Persians to continue on with their plan of taking the walls down. With how the Roman soldiers were found, and the position in which they were in, archaeologists determined that the Persians successfully pulled off the chemical combat.

Even though the Persian’s were successful in setting up their plan to bring down the walls, they still were unable to actually bring them down, however, evidence shows that they still were able to break into the city. University of Leicester archaeologist Simon James excavated a ‘machine-gun belt’ which looked to have been the Roman’s last line of defense that was never put into effect. One can infer that the people of the city were either slaughtered or driven out of the city, leaving Dura-Europos abandon forever. Although there was not much physical evidence at hand, archaeologists were able to figure out just what went down at this ancient city based on the 19 dead soldiers found in the mines.

Sources:

1. University of Leicester. “Archeologist Uncovers Evidence Of Ancient Chemical Warfare.” ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 15 January 2009. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/01/090114075921.htm>.

2. http://www.livescience.com/13113-ancient-chemical-warfare-romans-persians.html

Pictures:

1. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/01/090114075921.htm

2. https://gatesofnineveh.wordpress.com/2012/05/10/more-inventions-of-the-ancient-near-east/

Further Reading:

1. https://gatesofnineveh.wordpress.com/2012/05/10/more-inventions-of-the-ancient-near-east/

2. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/09/05/poison-gas-ancient-syria-chemical-warfare_n_3876017.html

3. http://www2.le.ac.uk/departments/archaeology/people/james/roman-soldiers-in-the-city/final-siege

4. http://io9.com/5798230/ancient-chemical-weapons-that-were-ahead-of-their-time

This excavation reveals the multiple types of analysis that may be simultaneously employed within in a single archaeological site today. Archaeologists here examined the visible, physical comportment/arrangement of the skeletons alongside a more microscopic analysis of chemical compounds found within the space. They then were able to relate this to a larger narrative of interactions between different peoples. What other types of analysis were at play during this investigation that contributed to the ultimate conclusions drawn by researchers? How does this research affect the way we approach and understand chemical warfare today?