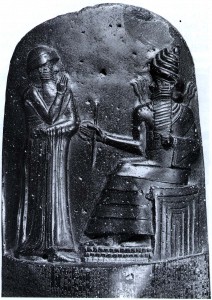

Hammurabi’s code is a series of 282 laws from ancient Mesopotamia (around 1727 BCE) that is well known for its harsh ruling on crimes as well as its distinction between classes and gender.

What gave Hammurabi the right to rule in the first place?

Hammurabi descended from a line of kings so the continued rule by his family line would be considered the “norm.” In addition to this, his affiliation with the gods, and his popularity for expanding his empire gave him power.

He unites people under this shared document. Ruling 195 states that, “If a son has struck his father, his hands shall be cut off.” This same punishment is also applied to a surgeon who has killed or “cut out the eye” of another. Law 196 is the famous “eye for an eye,” case, followed by teeth and genitals.

From a biological imperative standpoint, our ability to perform specialized tasks with our hands, to avoid dangerous situations with our vision, to process foods that are otherwise too hard for consumption, and to reproduce, thus passing on our genes, are all evolutionary advantages. The code focuses on the essential functions while omitting features that could be lived without. The harsh environment of Mesopotamia led to a desire for individuals to pull their own weight, thus setting criminals, now disabled, up for resentment and “other-ing” by the rest of the society. The absence of one’s hands is immediately apparent, and therefore a permanent badge of misbehavior.

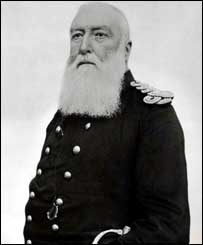

3600 years after Hammurabi, King Leopold II (see below) began his exploitation of the “African cake.” Under the same idea of expansion, King Leopold used his “right” as a European to civilize the people of Congo, while in reality profiting from growing rubber and ivory industries that resulted in the enslavement of the local peoples and the deaths of approximately 10 Million.

King Leopold’s army added insult to injury, so to speak, by damaging the bodies of the dead, even hanging them “in the form of a cross.” A cross, a symbol of Christianity (a European idea), becomes a symbol of terror for the survivors.

His war crimes included mass mutilation where “They [hands] became a form of currency,” proof that bullets were not “wasted.” Again, the removal of hands is a means of exerting power over the socially inferior group. By allowing the trade of severed hands, the victims of this genocide are dehumanized. Amputation is not always fatal, allowing the person to live for years with this form of mutilation. As in Hammurabi’s time, these people also had to bear the physical signs of oppression.

Warfare is a matter of intimidation, often seeking to “warn off” outsiders. So who would be left to intimidate if war were more “efficient?”

This reasoning would help explain why the removal of hands has been a punishment over the centuries.

Read Hammurabi’s code here:

http://eawc.evansville.edu/anthology/hammurabi.htm

The idea is even brought forward into the modern day:

Photos:

http://www.historians.org/teaching-and-learning/classroom-content/teaching-and-learning-in-the-digital-age/images-of-power-art-as-an-historiographic-tool/stele-with-law-code-of-hammurabi

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/3516965.stm

“Ancient History Sourcebook: Code of Hammurabi, C. 1780 BCE.” Internet History Sourcebooks. Ed. Paul Halsall. Fordham University, 6 Nov. 2014. Web. 22 Nov. 2014. <http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/ancient/hamcode.asp>.

Ceallaigh, Liam O. “When You Kill Ten Million Africans You Aren’t Called ‘Hitler'” Diary of a Walking Butterfly. Diary of a Walking Butterfly, 22 Dec. 2010. Web. 20 Nov. 2014.

“The Code of Hammurabi.” Constitution Society. Constitution Society, n.d. Web. 18 Nov. 2014.

James, Andre C. “The Butcher of Congo: King Leopold II of Belgium.” Digital Journal. Digital Journal, 4 Apr. 2011. Web. 21 Nov. 2014.

Knox, Gordon. “Heart of Darkness – There Was Nothing Exactly Profitable in These Heads Being There.” Book Drum. Book Drum, 2013. Web. 22 Nov. 2014.

Selwyn-Holmes, Alex. “Congo, Then and Now.” Iconic Photos. Word Press, 10 Feb. 2011. Web. 22 Nov. 2014. <http://iconicphotos.wordpress.com/2011/02/10/congo-then-and-now/>.

Sliwinski, Sharon. “The Kodak on the Congo: The Childhood of Human Rights.” Academia.edu. Academia.edu, 2010. Web. 22 Nov. 2014. <http://www.academia.edu/2464487/In_the_early_1900s_the_missionaries_Alice_Seeley_Harris>.

Stolze, Dolly. “A Criminal’s Relic: The Macabre History of Severed Hands.” Strange Remains. Strange Remains, 6 Apr. 2014. Web. 18 Nov. 2014.

It’s always fascinating when similar practices appear at different times and in different places. In both ancient Mesopotamia and 19th century Africa, the practice of cutting off hands functioned as a form of punishment that carried largely negative connotations. By first recognizing these similarities, we can then engage in comparison and recognize how different they actually are. For example, while this practice was motivated by a desire for power in both instances, the goals of those executing the punishment and broader power relations in society vary greatly. In both instances, hand cutting served as physical and symbolic punishment. However, this symbolism carried divergent meanings and resulted in different social consequences. I am curious if there are other instances of this practice elsewhere, both similar and different to the three mentioned here.