A team of Yale Archaeologists led by Professor of Egyptology John Coleman Darnell discovered a “lost” Egyptian City while on their “Theban Desert Road Survey.” This survey is a rolling mission in which the goal is to map out and study the Egyptian Western Desert and its ancient caravan routes. Through this survey, the Yale archaeologists discovered the so-called “lost” ancient Egyptian City, Umm Mawagir. The discovery of this city answered and sparked up a lot of questions about the Second Intermediate Period in the Theban Western Desert. The period of time between 1650-1550 BC is known as the Second Intermediate Period consisting of three main groups in the Western Desert; they are the Hyksos, the Nubian kingdom of Kerma, and Thebaid. This time period represents the second time that Egypt fell into chaos right after the end of the Middle Kingdom and before the start of the New Kingdom. The recently discovered city spans over a kilometer in the southern part of the Kharaga Oasis, which before this discovery had been thought of as an uninhabited ghost town. John Darnell, however, believes that this Oasis was actually a center for caravan routes connecting the Nile Valley of Egypt to modern day Western Sudan.

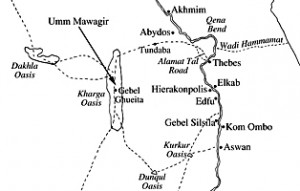

Map of the area around Umm Magawir, which was originally proclaimed a wasteland until discovered by Darnell and his team of archaeologists

“The Western Desert of the Second Intermediate Period may well have been wild, but it was not disorganized,” stated Darnell as he reflected on his discovery. Darnell also believes that this ancient city was at one point in association with Thebes, which may be able to explain how the Pharaonic power prevailed as the weakest of the three establishments, possibly leading to the early start up of the Golden age of the Egyptian Empire. One of the main reasons this city was able to survive was because it produced a sizeable amount of bread at that time. Having the ability to produce this much bread allowed the city to flourish through trade in the Western desert region. Darnell was very interested about why the baking of bread was such a big deal in this particular city so he and his team decided to start a dig in a part of the bakery. The team of archaeologists was able to find close to half a ton of pottery in a relatively small area that caught Darnell’s attention right away.

Bread forms that were excavated from the ancient city Umm Magawir. Umm Magawir means “Mother of Bread Molds”

In just that one dig they were also able to find two large baking ovens, stones for grinding flour, and a stone mortar for husking grain. As the team began to search around for more information, they were able to find broken pots of Nubian Desert troops, which suggested that this city had once served as a major military stronghold for these highly valued soldiers because the only way for these pots to have gotten to Umm Mawagir is if they were carried up from the south. The excavation is nowhere near done, with only about one percent of the city excavated. Darnell believes that through further excavation archaeologists will be able to find things out about the Second Intermediate Period that have been left unanswered.

Sources:

http://www.yalealumnimagazine.com/articles/2979

http://news.yale.edu/2010/08/26/ancient-lost-egyptian-city-discovered-yale-archaeologists

Renfrew, Colin, and Paul G. Bahn. Archaeology essentials: theories, methods, and practice. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Thames & Hudson, 20102010.

Additional Reading:

http://www.yale.edu/egyptology/ummmawagir_ceramic.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/07/science/07archeo.html?_r=0

When we conceptualize the ancient past, many often assume that communities existed as self-sufficient, independent entities. However, excavations such as that at Umm Mawagir, counter these assumptions and generalizations. The findings at this excavation show that not only were many ancient communities engaged in rich networks of trade and communication, but also that these trade networks were essential to their survival. The bread molds found give us information about the types of objects traded, while the broken pots of Nubian Desert troops tell us about the different types of people who passed through the town. The simple presence of broken pots and molds reveals complex and intricate relationships and interactions. I am curious as to whether similar objects were found in nearby towns. What other methods can archaeologists use to make connections between sites, cities and societies?

Seeing the past peoples and cities as isolated elements of the landscape is a major problem in everyone’s understanding of the past. If we were to emphasize how interconnected past communities were it would be easier to combat ethnocentrism and racism. None of us are descended from a single identity, we are all part of the mixture of past peoples who migrated around the globe.