Heather Gill-Robinson began her career as an archeologist just like we are, by taking an introductory anthropology class. She learned, as did we, that in wetland sites, “organic materials are effectively sealed in a wet and airless environment which favors preservation.” (Renfrew 54) Gill-Robinson’s first connection to the bog bodies, which she so heavily studies now, was via a picture of the head of the Tollund Man, Figure 1.

Figure 1: A close-up view of the Tollund Man’s head, an image similar to that which Gill-Robinson saw.

The Tolland Man is the best-preserved bog body. Found in a bog near Bjældskovdal, Denmark on May 6th, 1950, the Tolland Man has been dated back to the Early Iron Age, or around 500 B.C. Gill-Robinson was amazed at the condition of the Tolland Man and wanted to learn how his body had been preserved for thousands of years. When her professor told her that researchers were still unsure how the preservation worked, Gill-Robinson decided that she wanted to perform research in order to find the answer; and research she did (in the form of experimental archeology).

In 1999, the New York Times picked up on Gill-Robinson’s bog research and wrote an article on her findings. Gill-Robinson, then a forensic support technician for the Belleville Police Department in Ontario, Canada, wanted to look into causes of decay in order to more accurately predict the time of death of discovered bodies. She chose to use piglets in her research for multiple reasons, the first of course being that human cadavers aren’t readily available, and the second being that piglets have many biochemical and physiological similarities to humans.

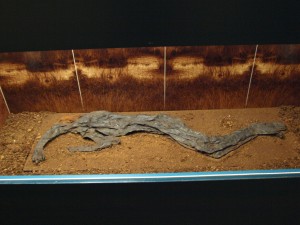

Gill-Robinson buried 14 piglets in three bog areas in England and Scotland, leaving each piglet in anywhere from 6 months to 28 months. After taking each of the piglets out, Gill-Robinson began to notice patterns. First, she noted that pH did not play a significant role in bog preservation, due to the fact that independent of their bog placements, in which the pHs differed greatly, the three piglets uncovered at the same time (regularly within the first few weeks) had undergone similar stages of decomposition. Also, the key find in her experiment was that the best-preserved piglets were buried in the peat bogs with the highest water levels. Gill-Robinson called this “Wetter is better.” (New York Times) Today, Gill-Robinson is focusing on the use of CT scans as a non-destructive analytical tool for bog bodies. She used a CT scan on the Damendorf Man, a bog body that everyone assumed had no bones left, because it was so flat, Figure 2.

By using the CT scan, Gill-Robinson was able to find 5 vertebrae, the pelvis, and both thigh bones in the Damendorf Man. Not only did she find his bones, Gill-Robinson also found his brain, which had shrunk to a few inches long and half an inch thick. Using the CT scan’s imaging software, she was able to print a perfect replica of the well-preserved brain. Gill-Robinson started just like us, and look how far she’s come!

Sources:

http://archive.archaeology.org/online/interviews/heather_gill_robinson/

http://www.nytimes.com/1999/08/17/science/piglets-buried-in-bogs-a-clue-to-mystery.html

http://www.tollundman.dk/default.asp

Renfrew, Colin and Paul Bahn (2010) Archaeology Essentials. 2nd edition. Thames & Hudson, New York. Chapter 2.

Figure 1: http://www.tollundman.dk/gifs/tollundmanden_2-350.jpg

Figure 2: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/0c/Damendorf_Man.jpg

Further Reading:

http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2007/09/bog-bodies/bog-bodies-text

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/09/070908095852.htm

When I first read your blog post, I was struck by the first image of the Tollund Man. The close-up view of his head was arresting — the well-preserved features and skin almost gave me the impression that I was looking at the face of a living person. This type of find differs greatly from what many people typically think of as an “artifact.” In archaeology, we often access the past through more abstract artifacts (i.e. pottery, tools, bones). These reveal vital information about the practices, values, social organization, etc. of a people, but rarely are so immediately accessible and recognizable. The work on bog bodies was indeed so fascinating that it garnered major media attention, as you mentioned, and was interesting enough to you that you decided to dedicate a blog post to it. These responses to the bog bodies lead me to question both why this type of archaeology is so compelling and what it reveals about history. Immensely tangible, does the Tolland man humanize a past that sometimes may be hard to conceptualize? In what ways do these preserved bodies alter the way we access history?

Soil pH has a long history as a standard excuse for why organics are or are not found in sites. As a former analytical chemist I have always questioned this. In one site report the bones of a human fetus are described while the lack of animal bones at the site is discounted due to soil pH. That is non-sensical. In some cases soil pH accelerates decomposition but in some cases the bones may be missing for cultural reasons.