It is so interesting how the study of the past can be so relatable to today’s current issues, including sustainability, warfare, and more. By studying the different ways that past cultures and societies have been set up, we can see what worked for them and what mistakes they may have made. That way, we can try to correct those mistakes and improve upon our own societies in the modern world. One aspect of our studies and readings this week that I thought was particularly interesting was looking at warfare through archaeology. By understanding conflict and war in the past, we can better understand what happened (what started the conflict) so that we can have an improved knowledge of how to deal with conflict today. It is very fascinating that almost all warfare and conflict is based off of disputes over territory in one way or another. This is not a new concept, people have been involved in wars for hundreds of years, it is only the nature of wars that has changed.

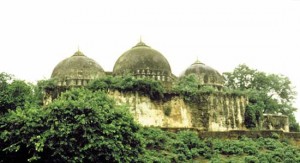

An example of this idea of archaeology in warfare is seen in a conflict between Muslims and Hindus over the ownership of the 16th century Babri Mosque in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh. This mosque was said by some Hindu groups to have been built (in 1528) by Muslims on a place where a Hindu temple used to have stood that marked the birthplace of the mythical king, Rama. The temple was closed for a while after it was rededicated as a place of Hindu worship, right after Indian independence from Britain. Then in 1986, a judge ordered that it be open, as a place of Hindu worship.

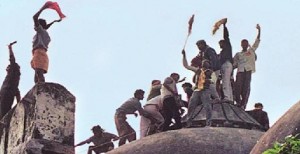

This was greeted with resentment and anger by Muslims, who believed that this building truly belonged to them. Soon, protests and conflicts occurred. In 1990, the national government tried to have negotiations that would try to determine whether or not this building belonged to Hindus or Muslims. These negotiations, however, were not successful. In 1992, Hindu militants destroyed the mosque.

Archaeology was used in this case to try to analyze the stratigraphy in order to see whether or not it was inherently a Hindu temple or not. Interpretations of this archaeological data, however, have varied widely. It is difficult to try and analyze stratigraphy of a site because of the fact that it usually does not consist of a distinct transition from one time period to another. Everything seems to mesh together and it becomes difficult to interpret. It is also, in general, dangerous to be an archaeologist who has something to prove. That could create a certain dishonesty of the true results. The archaeologist must always be open to all results and must not have a bias.

Image Sources:

http://www.newsyaps.com/not-ram-not-allah-20-years-of-babri-masjid-demolition-in-pictures/4013/

http://bharatabharati.wordpress.com/2010/09/25/archaeology-was-there-a-temple-at-the-ramjanmabhumi-before-the-babri-masjid-was-built-b-b-lal/

In cases like Ayodhya, cultural conflict certainly complicated excavation and analysis of the site. In other cases, though, intercultural conflict can actually support archaeological research, as in the case of the U.S. invasion of Iraq. Just after the U.S. invasion of Iraq, a team of American archaeologists excavated a 1988 mass grave in Iraq’s southern Muthanna province. In her 2009 article “Witness to Genocide,” Heather Pringle examines the 2005 excavations of this mass grave, a secret burial of Iraqi Kurds killed during Operation Anfal. Working fast to avoid drawing the attention of insurgents, archaeologists catalogued the 114 individuals buried in the mass grave. The victims were almost exclusively women and children; of the 114 victims, only 30 were adults and only 2 were men. The mass graves show clear intentionality and were likely dug in advance. Personal effects of the victims confirmed their Kurdish identity, since “more than 80 percent of the victims wore at least one article of traditional Kurdish clothing or possessed Kurdish jewelry, cosmetic kits, or sachets.” The archaeological findings of these excavations later became key evidence during the trials of Iraqi war criminals; in the end, Saddam Hussein and five other defendants, including Ali Hassan al-Majid al-Tikriti, better known as “Chemical Ali,” were charged with genocide and crimes against humanity for their involvement in Operation Anfal. It is important to note that the United States government had its own motivations for investigating this massacre, namely to drum up support for the Iraq War, and the role that politics can play in shaping archaeological research.

Pringle, Heather. “Features: Witness to Genocide.” Archaeology 62.1 (January/February 2009).