When one hears the world archeology, (one unknowledgeable or untrained in the discipline anyway), images of Egyptian pyramids and cities filled with treasure buried in the jungle come to mind. But the real “treasure” of archeology of course, is what the artifacts that remain after a civilization is long gone, tell us about the culture and history of the people who left them behind, in ways that the written record simply cannot.

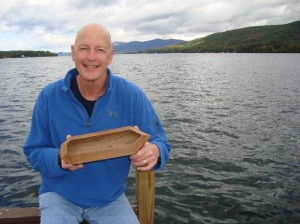

You may be surprised to learn that some archeologists never even put shovel to earth. Joseph Zarzynski is just such an archeologist. A soft-spoken, balding man with an infectious grin, he maps and explores the sea bottom. Yet, the fascinating artifacts he uncovers rival anything found in a subterranean vault.

You may be surprised to learn that some archeologists never even put shovel to earth. Joseph Zarzynski is just such an archeologist. A soft-spoken, balding man with an infectious grin, he maps and explores the sea bottom. Yet, the fascinating artifacts he uncovers rival anything found in a subterranean vault.

Zarzynski spoke with our class about his team’s investigation of sunken ships in Lake George, left behind during the French and Indian Wars of the 18th century. One must understand that Zarzynski and his team did not just arbitrarily decide to explore Lake George. First they undertook a comprehensive examination of the history of that period. Apparently, during that time period waterways such as Lake George were a source of transport and trade as well as home to a variety of military encampments. Often vessels were purposely sunk in the shallows ahead of the coming winter to prevent opposing troops from utilizing or burning them. Then, using the scientific method, they formulated a research question, decided the best way to explore their question, acquired and processed data, and then analyzed and interpreted the data. Their chosen site still was not easy to explore due to the many administrative headaches they encountered in acquiring permits for their dives.

What they ultimately found in Lake George was an intact radeux, (French for raft), which had been intentionally sunk. However the depth of the lake that area was too deep to make raising the raft feasible in the 1700s. Thus, this 52 foot long, 82 foot wide floating gun battery known as the “Land Tortoise” was still there to be found in 1990; the earliest known warship of its kind. The “raft” contained no gold doubloons or six headed statues, and in fact, the ship was never even raised, but it contained provided priceless information about the time period when it was created.

The discovery of the Land Tortoise lead to the creation of the 1987 Abandoned Shipwreck Act, and the New York State Submerged Heritage Preserves. In fact, in 1998, the Land Tortoise was declared a National Historic Landmark. Better than any book about the period, the maps and photographs captured by Zarzynski and his team, bring alive that time in history when Lake George was a site of war instead of a picturesque tourist destination. That is what real archeology does.

The discovery of the Land Tortoise lead to the creation of the 1987 Abandoned Shipwreck Act, and the New York State Submerged Heritage Preserves. In fact, in 1998, the Land Tortoise was declared a National Historic Landmark. Better than any book about the period, the maps and photographs captured by Zarzynski and his team, bring alive that time in history when Lake George was a site of war instead of a picturesque tourist destination. That is what real archeology does.

The Land Tortoise dates from 1758, three years after the Battle of Lake George took place on September 8, 1755. The battle pitted 1,500 French soldiers against an equal number of British soldiers, along with 200 Mohawk Indian allies. Seen as a turning point in the French-Indian war, the Battle of Lake George was the first major battle won by colonial American troops and their American Indian allies; while fighting continued at nearby Lake Champlain, most of the French troops moved north and vacated the Hudson Valley, which quickly fell under British control. An excavation of the battleground at Lake George, not far from the submerged shipwreck, may give even more insight into the war technologies and strategies espoused by both armies during the French-Indian war, as well as putting the Land Tortoise in more historical context.