Heinrich Schliemann. Few have given and simultaneously taken so much away from a field of study. Today Schliemann is best known for being the man who found the likely site of the previously assumed mythical city of Troy, the very same city that was supposedly besieged for ten years by Aegean warriors led by Agamemnon, the city that saw the death of Hector and Achilles and was burnt to the ground after accepting a inconspicuous wooden horse into its walls. The very mention of its name conjures up images of a time when gods spoke to men and a species of heroes fought to the death for glory. And this man, Schliemann, is the one who found the city Homer sang about, and what a magnificent find it is. If only Heinrich Schliemann weren’t also the man who destroyed it.

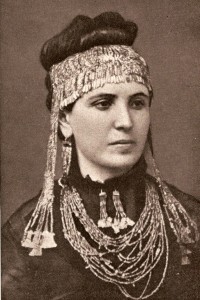

To modern archaeologists, Schliemann serves as more of a cautionary tale than anything else. His overly ambitious attitude in the Troy and other digs exemplify a disposition that seeks to confirm preconceived notions about the past rather than discover what the evidence actually suggests, one that desires treasure, fame, and a compelling narrative more than anything else. Having set out with the intent to find the city of Priam in all the glory Homer lends it, Schliemann became unable to see anything as he dug into the hill known as Hisarlik but gold. Indeed, he dug and dug, destroying the stratified ruins of many past Troys until he came upon a layer he deemed acceptable of the name. The Troy he took to be the one of legend (today referred to as Troy II) shows evidence of a fire and contained “Priam’s Treasure” including the “Jewels of Helen.” As would later be discovered, Troy II also happened to flourish about 1000 years before the Trojan War supposedly happened, meaning the remains of Homer’s Troy were likely largely destroyed by the spades of Schliemann. (Fields 10)

Broadly, the story of Schliemann can be used to highlight particular challenges faced by archaeologists if impartiality is to be preserved. Schliemann was a product of a culture that revered classical Greece perhaps excessively. Without any reverence for the history of the site beyond his narrow interpretation of its importance, he not only failed to find the information he sought, but also disregarded and disrespected the millennia of civilizations that existed on that hill in Turkey. Regardless towards whether or not Hisarlik is the location of Troy in actuality, the sheer volume of material evidence found in it is large enough to be invaluable to a study of past cultures of the region. But as far as Schliemann was concerned, there was nothing of importance there that wasn’t related to one ancient Greek myth, ironically causing him to ignore the only layer of the site that possibly could be related to it. His story should serve as a lesson to all archaeologists: Don’t allow biased expectations get in the way of what the evidence suggests.

Further Reading

- Fields, Nic. Troy c. 1700-1250. Osprey Publishing. Oxford, UK. 2004.

- Wood, Micheal. In Search of the Trojan War. University of California Press. Berkley and Los Angeles, California. 1998.

Images

Modern anthropologists working today often struggle with the careless (by today’s standards) methods of archaeological excavation. I worked at a site in France, La Ferrassie, this summer, which was first excavated in 1909; the two excavators, Louis Capitan and Denis Peyrony, only kept the artifacts they deemed nice enough, and tossed the rest, along with tons and tons of dirt that they didn’t sift at all. This experience is paralled at the excavation of the Emeryville shellmound, a highly important native Californian site that heavily excavated in 1906. The shellmound contained remnants of settlements, human burials, artifacts, and countless shells, and much of its content and certainly its stratigraphy were destroyed or displaced (without context) by its excavators. With this in mind, how can we assess the early archaeological work, given its haphazard methodology? Is it possible to glean more from returning to these sites or reanalyzing early data, or, like Homer’s Troy, is it all irrevocably lost?