One of the reasons that people don’t understand archaeology is the fact that archaeology can be manipulated to either fit with or alter the public’s perception of the past. For example, the Cardiff Giant hoax centered on a supposed “large, petrified body” found by the farmer Stub Newell in 1869. People travelled for miles and paid rising entry fees to catch a glimpse of it. Over time, the giant’s popularity mounted, despite the fact that several archaeologists and scientists examined the body and declared it to be a fake, citing the soft stone, tool marks, and lack of deterioration as indicators that it was not nearly as old as Newell claimed it was. Eventually, Professor Othniel C. Marsh deemed it to be a “remarkable fake”, and it was revealed that Newell’s relative George Hull had commissioned the sculpture and gone through great lengths to disguise it as an ancient being.

The people’s continued belief in the Cardiff Giant exemplifies the use of archaeology to fit with a common belief. In the 1800s, the stories of the Bible were seen as truths rather than allegories. Therefore, those who believed the biblical tales of giants roaming the earth were delighted to find proof of these stories, and clung to it despite growing evidence of the hoax. While in reality, ancient peoples may have found large, extinct animals and simply thought they were giants, in the religious 19th century, holy texts were absolute. In this way, archaeology can blind people to the truth just as easily as it can enlighten them through offering a confirmation of spiritual beliefs. (Feder)

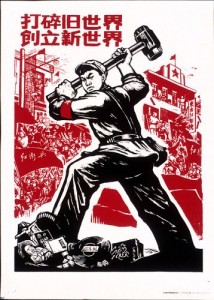

At the opposite end of the spectrum lies the destruction of ancient relics in China. China’s cultural revolution involved not only the reshaping of socioeconomic structure but also the complete elimination of the structure that had preceded it. As a way of insuring that citizens fully embraced the new, communist society, the government destroyed many artifacts and buildings dating to the dynasties of China’s greatest emperors. Destroying these relics not only prevented people from studying past cultural practices but also kept them from the very thing that the Cardiff Giant allowed—confirmation of a past that they might long for. Even though Chinese citizens have offered to pay for the conservation of certain relics, the government has denied these requests. (http://www.dailymotion.com/video/xsz70u_chinese-historical-relics-systematically-destroyed_news)

Both of these examples relay the way in which archaeology can give people hope by revealing an aspect of the past they believe. While some, such as Newell and Hull, use this power to make money, others wish to use it to understand their own fading heritage. Along this range lie many pitfalls and ulterior motives of people looking to uncover the past, which can lead to a misunderstanding of archaeology.