Anita Hemmings was Vassar’s First Black Student, but the College didn’t know that when it admitted her…

Anita Hemmings, 1897

Hemmings, the woman who would eventually be dubbed the “Brunette Beauty” during her time at Vassar College, was born on June 8th, 1872 in Boston, Massachusetts to Dora Logan and Robert Williamson Hemmings, who were both originally from Virginia. Dora and Robert wanted nothing but the best for their children, and that meant providing the means for them to have successful futures. Anita saw her successful future in education. She dreamed of becoming a teacher.

Girl’s English High School

During her early years, her parents sent her to the Girls’ English High School in Boston, MA before sending her to the Northfield Seminary (then Dwight L. Moody’s School) in order to prepare for the entrance exams for Vassar, one of the top women’s colleges in the United States. Karin Tanabe, author of The Gilded Years, a novel based on Anita’s life, details that “at the time, you had to take these rigorous entrance exams to get into school…tons of subjects – Greek, Latin, math…Anita studied for a whole year to pass that test at Northfield” (Laughlin). And pass she did.

When it came time for her to apply to Vassar, she and her family were faced with a dilemma. “At the end of the nineteenth century, only three of the Seven Sisters schools accepted African American students: Radcliffe, Wellesley, and Mount Holyoke” (The Gilded Years). Other than the few that were allowed to matriculate into predominately-white colleges, most “Colored” people attended historically black colleges, which were not as well funded or resourced as elite institutions like Vassar. This didn’t match up with the Hemmingses’ hopes of sending Anita to an institution that would provide her the highest quality education. She and her parents decided that the only way she’d be able to achieve her dreams was to pass as a white woman, so on her application to Vassar, she listed that she was English and French, as the application asked for your ethnicity – not your race.

Since Anita was lighter in complexion, she was able to pass. ‘”She has a clear olive complexion, heavy black hair and eyebrows and coal black eyes,’ a Boston newspaper wrote…’The strength of her strain of white blood has so asserted itself that she could pass anywhere simply as a pronounced brunette of white race'” (Mancini).

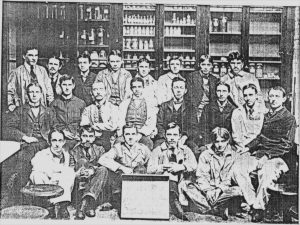

MIT Chemistry Class of 1897 || Frederick is 4th from center

She got into Vassar, and “all through her college years, Anita shuttled back and forth between elite Vassar and migrant black Boston, between rich white strangers and poor black family” (Sim). At the same time, her brother Frederick attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), but did not pass.

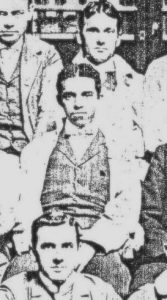

“Frederick had always been more cautious than his sister when it came to interacting with and befriending those outside the Negro community. His slightly darker skin, the fact that he had never passed as white for more than a few days, his reality of being a Negro student in a white world, and his naturally circumspect character meant he never dared take the risks his sister did” (Tanabe).

“Anita certainly fit in because she was smart and she was talented and she was curious,” Tanabe describes (Laughlin). She was an impressive student. Because of her brilliant mind and pre-matriculation preparation, she mastered Latin, ancient Greek, and French. Proving herself just as brilliant outside of the classroom as she was inside of the classroom, Anita also sung in the College’s choir as a soprano and was often invited to sing solo recitals at the local churches in Poughkeepsie, NY.

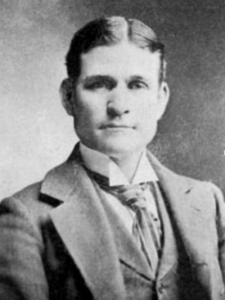

Frederick Hemmings

However, everything wasn’t all good at Vassar for Anita. During her first year at Vassar, the secret of her identity overwhelmed her so much that she decided to tell a professor about her black heritage. She trusted the professor enough to keep her secret and thought that admitting it to someone who she believed would hold on to it would rid her from the guilt of deceiving the College.

Though her professor wouldn’t be the one to “out” her as a black woman, Anita’s identity was eventually revealed. As she lived and learned as a Vassar Girl for the next couple of years, her classmates often wondered about her identity. Many of them believed her to be Native American or Spanish because of her strong black hair and olive complexion. But her roommate, Louise “Lulu” Taylor, thought differently.

Instead of opting to live in a dorm room by herself, where she could have a place to let her guard down, as far as her identity, Anita decided to have a roommate, so Louise entered into Anita’s life. In 1896, Anita and the girl from South Orange, New Jersey began to live together. Both of them were excited to live together and quickly became friends. However, it wasn’t long before Louise began to have her suspicions.

“The fall of their senior year, an item in the September 24, 1896 issue of the Boston Daily Globe mentioned the wedding of a prominent African American couple, Bessie Baker and William Henry Lewis. Among the list of bridesmaids, Louise spotted one familiar name: Anita Hemmings” (Laughlin). Louise wasn’t entirely sure about her suspicions of Anita having black heritage, but she decided to alert her father.

Her father turns his daughter’s suspicions into action. He decides to hire a private investigator to go to Anita’s hometown of Roxbury – a predominately black neighborhood in Boston – to find Anita’s family and uncover the truth once and for all.

And he does.

Clip from The Saint Paul Glob, 1897

He describes his findings to his daughter. Anita was a black woman, and she had deceived the entire Vassar community. Louise takes that proof to then-Vassar President James Monroe Taylor. He and the Board of Trustees began to come up with a plan for what to do with Anita: expel her, denying her of her diploma or allow her to graduate in hopes of having the Hemmings scandal blow over and be forgotten about. Taylor and the Board chose the latter. Anita “appealed to President Taylor, with the result that the girl was awarded her diploma.” “She took a prominent role in the exercises of Class Day, and no one who saw the Class of 1897 leave the shades of Vassar suspected Negro blood in one woman voted the class beauty” (Mancini). So, in 1897, Anita Florence Hemmings became the first-known black woman to graduate from Vassar College. But not without the ear of the country spreading news of the decision far beyond Poughkeepsie.

Clip from the Sacramento Daily Record Union, 1897

After graduating, Anita went to Martha’s Vineyard. Her mother ran a boardinghouse in the predominately-black area, so Anita went to work there for the summer, as was tradition for her. That was where she found out that the news of her graduation was spreading all over the country. Newspapers around the country were covering her story with headlines like “Vassar’s Colored Graduate,” “Vassar Graduated a Colored Woman,” and “How a Negro Girl Slipped through Vassar College.”

Clip from the Pacific Commercial Advertiser, 1897

“At the time, some colleges allowed select African American students to enroll. Of course, Vassar wasn’t one of the them. But even then, only one or two students would be admitted, and they definitely wouldn’t share rooms with white students” (Laughlin). So, people all over the country were shocked to hear that this could happen at such an elite school.

Tanabe describes “They [also] printed her address, they drew a picture of her house, so you have a picture of her house, you have a picture of her face, you have her address, it’s pretty darn easy to stalk this girl. She sort of went into hiding after that” (Laughlin). She went on to become a cataloger at the Boston Public Library for several years, ending her dream of being a school teacher. On October 20, 1903, she married Dr. Andrew Jackson Love, a physician practicing in New York City. He was also passing as white. He claimed to have graduated from Harvard Medical School, but was really a graduate of Meharry Medical School, a historically black school in Tennessee (he was listed as “colored” during his time there). In fact, Anita and Andrew lived in Tennessee for a brief time before relocating to Massachusetts in 1905, when Andrew was a postgraduate student at Harvard for the summer. According to Anita’s great granddaughter Jillian Sim, both Anita and Love were listed as “Col[ored]” on their marriage certificate.

During her time working in the Library, Anita was interviewed by a Boston newspaper. It argued that “the ‘singular serious, frank…earnest girl’ never made any attempt to deny her African [American] background while in her hometown. ‘Miss Hemmings certainly did not go to Vassar under an assumed name, nor did she give a fictitious residence…Miss Hemmings has been too prominently and publicly identified with her parents’ people to allow any good excuse for the ignorance of her lineage which is attributed to her instructors and associates at Vassar”‘ (Mancini).

Dr. Andrew Jackson Love

However, Anita and Andrew, eventually settling in New York City, decided to raise their children, Ellen, Barbara, and Andrew Jr. They sent them to Horace Mann School in Manhattan and to an exclusive, all-white camp in Cape Cod. During her only visit to her daughter and her grandchildren, Anita’s mother was made to use the servant’s entrance of the building, instead of the front door.

Anita and Andrew hoped that all of their children would be academically-inclined. Ellen attended Vassar in 1923, and just like her mother, she passed for white. After finding out that Anita’s daughter was attending Vassar, Louise Taylor – Anita’s college roommate – exposed Ellen’s identity to the College as well. After graduating from Vassar, “Louise went on to earn her master’s degree in English literature at New York University and then taught history and mythology at schools in [her hometown] until the 1930s” (The Gilded Years). Unlike Anita, she never was married or had any children, hence the free time she had that allowed her to keep up with Anita and her family. In several letters, Louise explained to then-Vassar President Henry Noble McCracken that ‘her particular interest in the question came from her “own painful experience with a roommate who was supposed to be a white girl, but who proved to be a Negress’ (Mancini). McCracken, along with explaining that Ellen had been considered for admission as a daughter of an alumna, explained that ‘[the College is] aware, and we’ve made sure she’s in a room by herself. We don’t even know if [Ellen] is aware that she’s black” (Mancini). That same year, Ellen was able to track down her grandmother on Martha’s Vineyard and find out the truth about her family heritage, but she never told her family.

She took the secret to her grave. But before she died, she relayed the secret to a close friend.

That close friend, who Sim refers to as “Alice” in her article “Fading to White,” notified Sim’s mother of the secret after Ellen’s death, and from there, the family’s black heritage once again came to light. Since then, Sim has been tracking down information about her family and putting the pieces of a broken family puzzle back together. “‘My great-grandmother was the first black graduate of Vassar College. And there was the real secret,’ wrote Sim. ‘This was why my grandmother would not, could not, speak of her family. Grandma’s mother had been born black, and she left her black family behind to become white. An irreversible decision. A decision that would affect all the future generations of her family. I thought of my faceless black ancestors who watched their daughter Anita leave them behind for better opportunities, for a better life as a white woman. She had to pass as white to educate herself…She had to abandon the very core of who she was to educate herself” (Mancini).

Bibliography and Other External Links

For more information on Anita Hemmings:

»Paul Laurence Dunbar Fascination

»The Gilded Years by Karin Tanabe

»“Fading to White” by Jillian A. Sim