[This is Part 4 of “The Paisley Underground: The Mythic Scene and Los Angeles Legacy of the Neo Psychedelic 80s”]

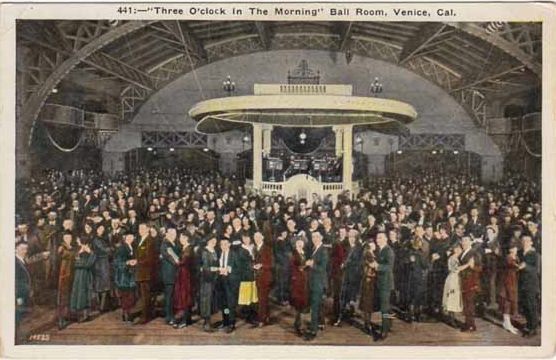

As this discussion underscores, it’s not at all obvious how the sounds, lyrics, and visuals of the Paisley Underground imagine Los Angeles as a place. Except for the obscure reference behind The Three O’Clock’s name (a 1920s ballroom on the Venice Beach Pier), there is little explicit in the Paisley Underground’s lyrics or imagery that refers to an L.A. setting. Relationship narratives may draw upon lyricists’ observations and experiences that took place in the city’s social milieu; in more inspired moments, the city itself might loom in psychological refraction; but otherwise L.A. tends to go lyrically unnamed and thematically undeveloped in Paisley Underground music. I read this manifest absence of Los Angeles signifiers, perhaps intended to resonate with wider audiences, as itself emblematic of a new turn in lyrical expression and creative praxis which the Paisley Underground introduced to Los Angeles underground rock and youth culture. This turn contrasts significantly with the youthful tribalism of L.A. punk, then riven between its arty Hollywood faction and the hardcore punk of the South Bay and Orange County (Spitz and Mullen 2001), as well as post-punk efforts to celebrate southern California’s blue-collar legacies like rockabilly (as illustrated by, e.g., the Blasters), country & western (Lone Justice), blues (Top Jimmy & the Rhythm Pigs), and Mexican styles (Los Lobos) (Doe and DeSavia 2019).

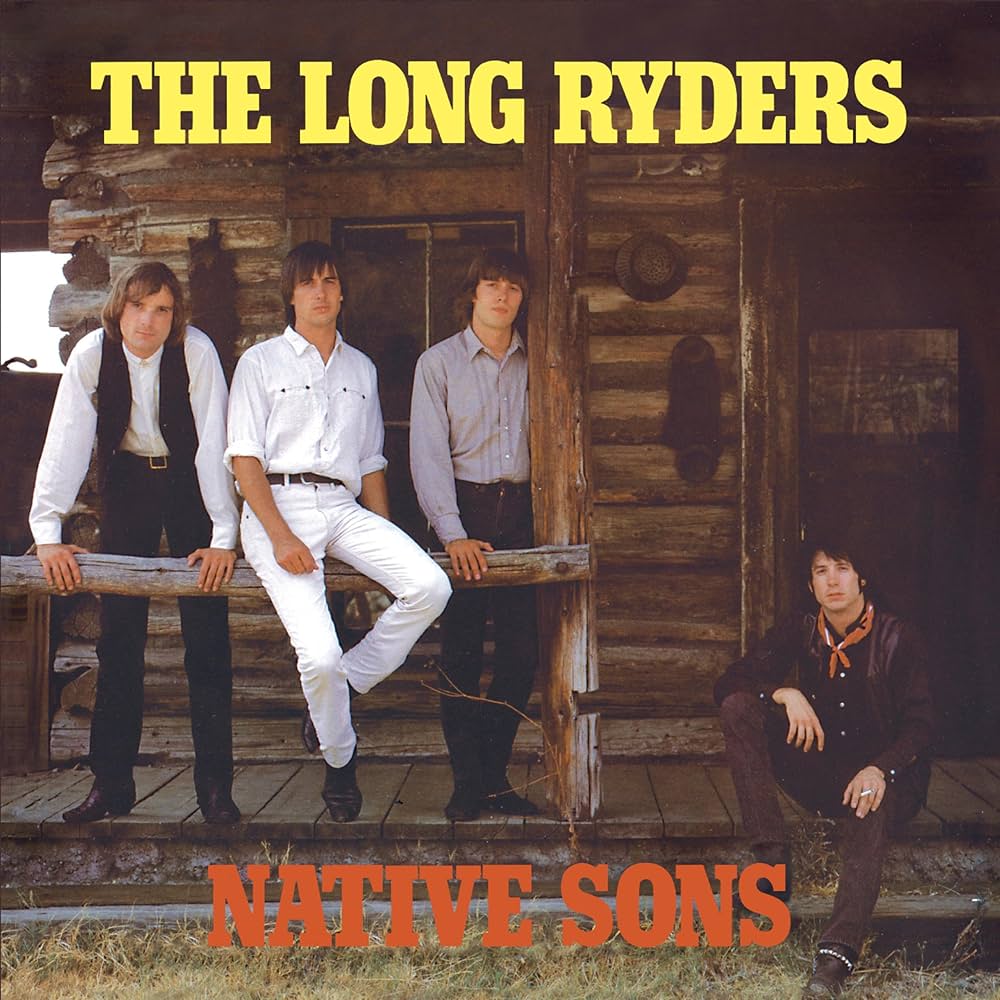

Arguably, the Long Ryders are the exception to this rule as the most regionally referential of Paisley Underground bands, staging the kind of rugged, rural setting for their Native Sons LP once seen on late 60s Southern California country-rock LPs (The Byrds’ The Notorious Byrd Brothers, The Flying Burrito Brothers’ The Gilded Palace Of Sin), and happily name-checking other Southern California groups who struggled to break out of the region. Still, what the Long Ryders share with other Paisley Underground bands is a willfulness to pluck out styles and motifs just past their sale date and synthesize them for new contexts. Perhaps this too is a local tradition of sorts, exemplified by southern California’s 1970s power-pop groups celebrated in the pages of Bomp! With the Paisley Underground, record companies and music media could declare this restoration of overlooked sounds itself a ‘new L.A. sound.’ Certainly, in contrast to the diminishing commercial returns experienced by X over five albums to establish a place for Los Angeles in rock’s lyrical archive, the Paisley Underground offered listeners a clean slate with which to jump into L.A. music. Yet the media portrayal of this ‘new old’ as a signature L.A. style was always an esoteric claim that these bands found awkward to sustain.

Significantly, as the Paisley Underground dissolved by the second half of the 1980s, L.A. rock’s musical tribes and imagined urbanisms were signaled with greater vigor and geographic definition by more commercially successful groups — Red Hot Chili Peppers (Hollywood), Guns ‘N Roses (the Sunset Strip), and N.W.A. (Compton), to name just three to influence the direction of alternative rock, heavy metal, and rap, respectively. From the gritty downtown milieu narrated by Janes Addiction, to even the glossy MOR pop mirror that Wilson Phillips held to generic, stucco-walled condominiums across the city, explicit representations and musical resonances of L.A. by local acts seemed to resurge as the new decade approached, even as the Los Angeles they evoked resided within familiar borders separating haves from have nots, white from non-white populations, civic order from neighborhood uprising. From this view of L.A. music history, the Paisley Underground’s legacy would seem to be quite simple: a brief flash of musical inspiration and excitement by a small clique of musicians who willed themselves into modest prominence from what was then an underrated region of rock’s underground. The media apparatus that narrated and broadcast this story of a ‘scene’ quickly turned its attention to other American cities with actual scenes: first Athens GA, then Austin, Minneapolis, Boston, Chapel Hill NC, and eventually Seattle.

Next – brave generation: presaging a new urbanism

THE ROAD TO THE PAISLEY UNDERGROUND: