[This is Part 3 of “The Paisley Underground: The Mythic Scene and Los Angeles Legacy of the Neo Psychedelic 80s”]

The interpersonal basis and private quality of the Paisley Underground finds further reflection when considering how these bands represented Los Angeles — or didn’t, as the case may be — in music, lyrics, and visuals. Here it’s necessary to decouple the local contexts and origins described in the previous section from these groups’ explicit references to and place associations with the city. The latter comprise the second “L.A. story,” given a semiotic-interpretive analysis in this section.

The artistic output of the Paisley Underground rests upon the live performances, publicity (in publications, radio interviews, etc.), album covers and marketing imagery, and of course the recorded music by these original bands. Virtually each of them garnered critical acclaim from music writers and underground cognoscenti for their first two releases, either LPs and EPs, released between 1982 and 1985 — the musical archive I emphasize here. In the grooves of this collective discography and the media attention that it received, a commonality is revealed by absent sounds of the era: new wave’s boxy beats and keyboard blurts, punk’s thrashing rhythms and vocal howls, and glam metal’s synchronized riffing and choreographed singalongs, all alive and well on L.A. stages at the time, never mind the mid-tempo shuffles and technical prowess of the southern California musicians who still had a lock on commercial FM radio. This absence, articulated by the Paisley Underground musicians and their media interlocutors as a conscious refusal, represented an authentic post-punk impulse: a collective effort at new syntheses and expressions in rock music, if not quite the generic innovations and deconstructionist turns associated with British and New York post-punk (Reynolds 2006), by musicians who had no significant role in punk’s emergence a few years earlier. In this way, these L.A. groups stood musically apart from the studied restorations of 60s garage rock and frat-house R&B associated with the east coast’s neo psychedelic progenitors like the Chesterfield Kings, the Fleshtones, and the Lyres.

Beyond their post-punk pedigree, however, the Paisley Underground comprised a musically and aesthetically diverse lot. At least three styles can be discerned in these bands’ musical approaches. The Bangles and The Long Ryders demonstrate 60s pop-rock pastiche in their early recordings, writing and arranging songs that repurpose retro elements (vocal harmonies à la The Beatles and The Mamas & The Papas for the former, the country-rock jangle of The Byrds and Buffalo Springfield for the latter). The Dream Syndicate and Green On Red utilize rock psychodrama, deploying raw instrumental attack and repetitive rhythms to animate their vocalists’ charismatic deliveries. Whereas these first two categories emphasize the neo- in neo psychedelia, Rain Parade, True West, and David Roback’s groups deploy classic rock psychedelia, favoring well-worn sonic signifiers (fuzztone effects, sitars) as well as musical techniques like plodding rhythms, backward-recorded guitars, vocals delivered with flattened affect, and in Rain Parade’s case an altered musical gravity (of the kind associated with vintage Pink Floyd) to evoke the sensation of mental trips, drug-based or otherwise. The Three O’Clock shift between 60s pop-rock pastiche (in their pop moments) and classic rock psychedelia (especially in their original Salvation Army incarnation, where their raw, speedy approach gave novel expression to a long-abused moniker, “flower punk”).

Lyrically, what made the Paisley Underground psychedelic? In interviews, musicians insisted, almost to a person, that drug usage was neither a lyrical emphasis nor song-writing method. As Susanna Hoffs said, “I was just a teenage experimenter who decided it was all just pretty much a waste of time… and a bummer for me” (quoted in Kalberg 1982). More ambiguously, David Roback acknowledged the shadow of drugs when writing Opal’s dream-like lyrics: “I’d say drug-like states play a role, not necessarily drugs. I haven’t been using a lot of drugs for a pretty long time” (quoted in Segal 1988, 69). The possibility here of a rehearsed response to assuage band publicists can’t be dismissed, considering how songs like the Rain Parade’s “1 Hour ½ Ago,” Green On Red’s “Illustrated Crawling,” and True West’s “Steps To The Door” recall the catatonic state of the acid-gobbling, snot-caked narrator of Love’s 1967 “Live And Let Live.” However, as The Three O’Clock’s Michael claimed, dream-like lyrics can also aim for “just surrealism,” that is, an idiosyncratic reinterpretation of everyday situations through fantastical visual associations:

It’s like things around me. And I’ll incorporate words like “a cantaloupe girlfriend”. That could be a very rich-type, beautiful-type girl, with the boyfriend in the M.G.[1] But you wouldn’t know that by how I’m saying it. I’m like the only person who would know what I am talking about. That’s just the way I am (quoted in Gumprecht 1983).

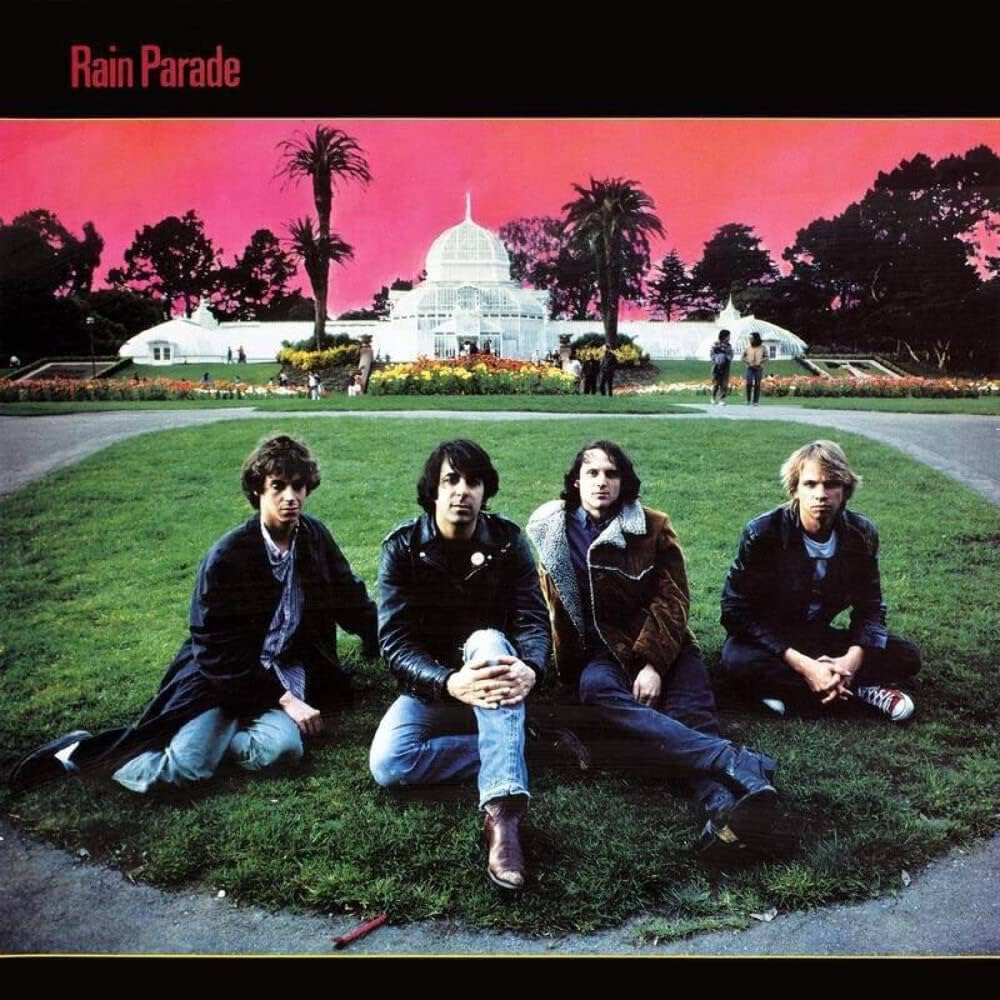

The Paisley Underground’s psychedelic foundation is more pronounced in the visual realm of album imagery, typography, and design. Victorian-era imagery and iconography appear on a number of Paisley Underground album covers, like The Rain Parade’s debut album Emergency Third Rail Power Trip (a partially colored photograph of a hot-air balloon festival), their follow-up EP Explosions in the Glass Palace (the band posed in front of the Victorian-era, glass-and-wood Conservatory of Flowers in San Francisco), and the cast-iron curlicue designs featured on Mazzy Star’s first two album covers. As with the paisley itself, a British colonial appropriation of Indian iconography that youth culture embraced in the Swinging 60s era, this ‘antique’ imagery harkens back to visuals and lyrics from the original psychedelic era, as exemplified by Sgt. Pepper-era Beatles and Syd Barrett’s Pink Floyd. What was then antique clothing and Victorian detritus resold in fashion boutiques receives an added element of playfulness with its improbable southern California reappropriation some two decades later. The cover of True West’s EP compilation Hollywood Holiday advances out-of-time imagery from the early 20th century, as art deco marble frames a still photo of airborne James Cagney from the 1942 air combat film Captains of the Clouds. A Rain Parade title conveys a psychedelic response to such fanciful anachronism: “This Can’t Be Today.”

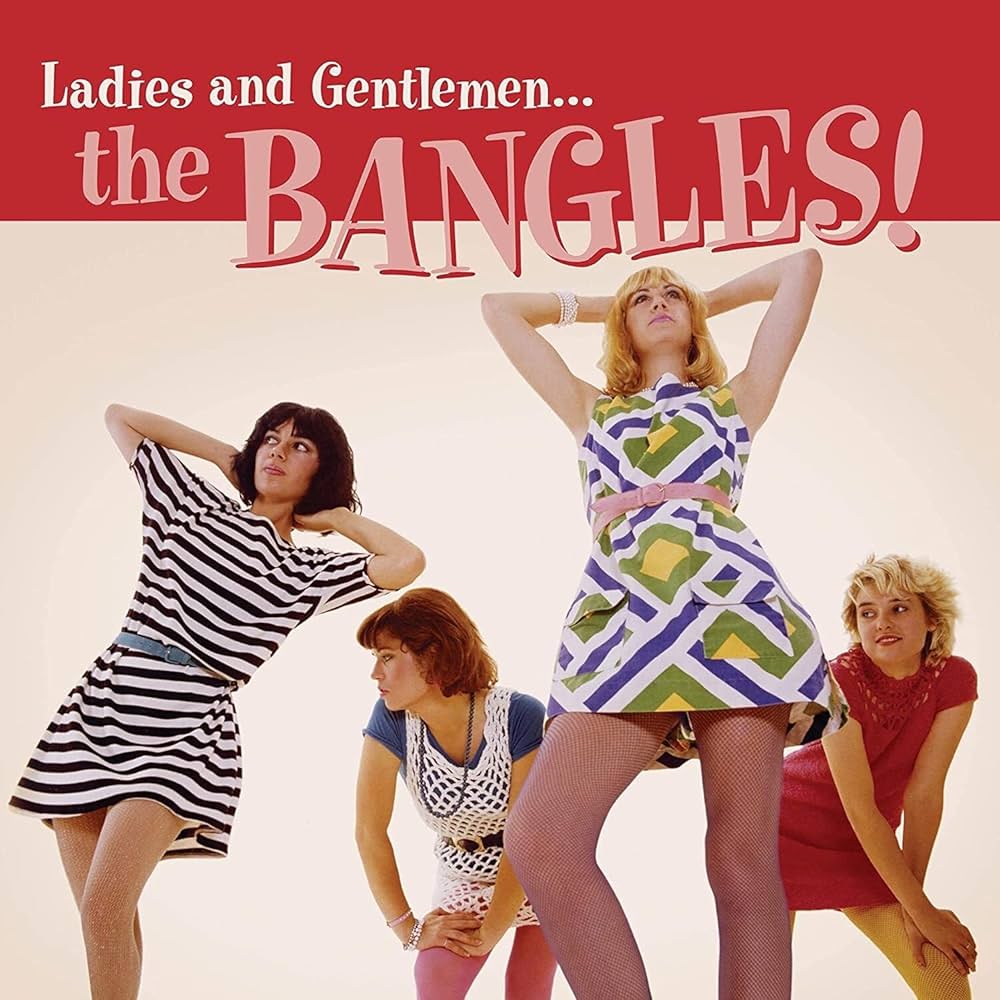

A shorter throwback to the mid-1960s appears in the “mod” touches of The Bangs’ mini-skirts (seen on the cover of Ladies And Gentlemen… The Bangles!, a 2016 compilation of Bangs material) and The Three O’Clock’s togs on their Baroque Hoedown EP. Flowers of the kind that decorate mini-skirts and circle Michael Quercio’s head on The Salvation Army’s self-titled debut album (a.k.a. Befour The Three O’Clock) refer to Swinging 60s design while simultaneously extending that decade’s psychedelic appropriation of Victorian “floriography,” the decorative language to communicate visually that which cannot be said aloud. ‘Baroque’ with a small ‘b’ speaks further to the spirit of these Victorian obsessions and the sensory frisson of the Paisley Underground’s semiotics. While The Three O’Clock and The Bangles acknowledged a debt to 60s “baroque pop” by The Beach Boys and The Left Banke, the term’s reference to intense ornamentation as an end in itself highlights the duality of these groups’ musical aims: the surface pleasures of pop music that is highly composed (in both songwriting and musical mannerism) but also a subconscious mode of expression unlocked through psychedelic experience.

These representational forays into dreams, surrealism, and psychedelia cast in sharp relief a countervailing lyrical default to conventional themes about personal relationships: romances, friendships, and the events that test them. Against stark or ragged musical accompaniment, these narratives provide fodder for hard-boiled drama and emotional revelation — a recurring strategy for The Dream Syndicate, with lyrics written exclusively by Steve Wynn. Alternately, atop 60s pop arrangements and vocal harmonies, they narrate youthful exuberance, jealousy, and lessons learned — a consistent mode in The Bangles’ songs, written by Susanna Hoffs and Vicki Peterson (and, by their debut album All Over The Place, outside songwriters too). The Long Ryders didn’t write “you and me songs,” Sid Griffin told music writer Bud Scoppa (1984), and “we certainly can’t write about surf or cars. So what’s left that we really care about is this country and how it affects us.” Still, the second-person “you” in their songs tends to wrestle with make-or-break moments of youthful ambition (“Final Wild Son”) and encounters with harsh reality (“Too Close To The Light”).

Reflecting the interpersonal network that bound their musical collective, interpersonal narratives are occasional foil for first-hand reflections about Paisley Underground musicians. Matt Piucci has explained he and David Roback, co-wrote “What She’s Done To Your Mind,” Rain Parade’s first single, to process the rivalry David felt seeing former girlfriend Susanna Hoffs strike musically before he did (Roberts 2020).[2] Steve Wynn (2018) reports The Bangles’ “Hero Takes A Fall” is about his excessive egotism after the acclaim given The Days Of Wine And Roses; the song accurately predicts Wynn’s comeuppance following the critical bruising given The Dream Syndicate’s second LP, Medicine Show. On Rain Parade’s Explosions In The Glass Palace EP, Matt Piucci’s “You Are My Friend” offers a tender if unflinching response to David Roback’s departure (Thomas 2022). Although sporadic in the collective discography, such lyrics of private reference illustrate more generally how the Paisley Underground narrates local moments of biographical transformations and interpersonal turning points while obscuring real names, situations, and settings.

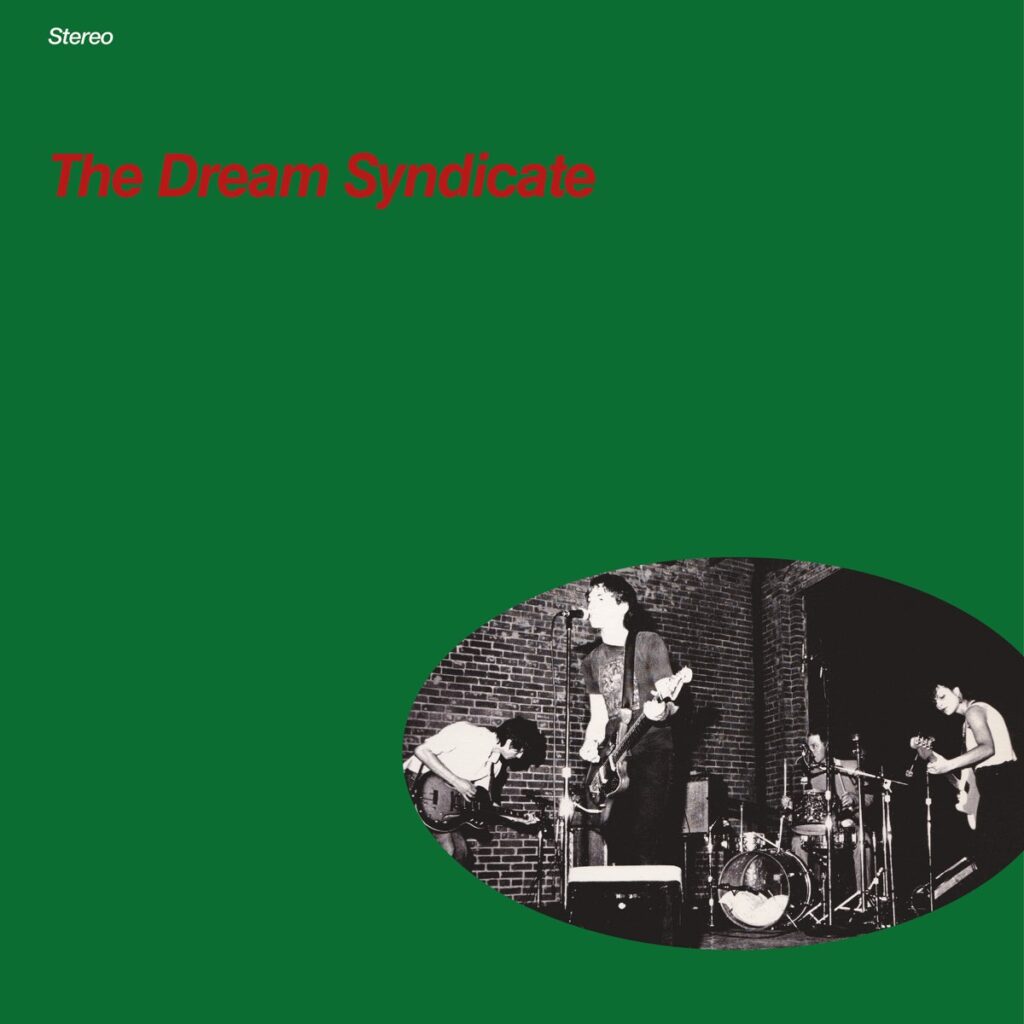

Also worth noting is the role of bygone literary and artistic styles in the Paisley Underground’s representations. In Green On Red’s “Brave Generation,” Dan Stuart reckons with the stream-of-consciousness tradition in American literature: “Yeah I was really in love with William Faulkner/My mother was a fish/But I never got across that river/It was just too long a trip… I’m not beat/I’m not hip/I’m the brave generation.” Creem writer Bill Holdship (1983) reports Steve Wynn professing the influence of Scottish essayist Thomas Carlyle, whose innovative 19th-century prose celebrated the mystery of everyday existence and depicted a universe suffused with creative energy (Cumming 2004, 454). The two bands share a further debt to post-WWII modernism. Film noir (particularly of the psychologically unsettled neo-noir variety) and crime fiction presage their lyrical scenarios of paranoid isolation (Green On Red’s “Apartment 6”) and explosive violence (The Dream Syndicate’s “Halloween” and “Until Lately”). Hip jazz modernism emanates from the covers of the two bands’ eponymous debuts, both released and art-designed by Wynn’s Down There Records, as well as The Dream Syndicate’s The Days Of Wine And Roses (a titular reference to the 1962 movie about a couple’s alcohol-soaked decline). With non-serif typography and bold monochromatic framing dominating most of their covers, these albums further echo the cool, urban minimalism associated with the art design of the Blue Notes and Impulse! labels (Marsh, Cromey, and Callingham 1991).

[1] Quercio refers here to the sporty British convertible then popular with affluent southern California youth.

[2] [Here I correct an error found in the print chapter that attributes the composition of “What She’s Done To Your Mind” solely to David Roback. I thank Matt Piucci for contacting me after this blog post was published and providing the correct detail: “It is about Sue, but I wrote and sang it. David helped me finish [it]. -LN]

Next – this can’t be today: the manifest absence of Los Angeles…

ROAD MAP TO THE PAISLEY UNDERGROUND: