[This is Part 5 of “The Paisley Underground: The Mythic Scene and Los Angeles Legacy of the Neo Psychedelic 80s”]

However, the third L.A. story of the Paisley Underground emerges from their postscript. The time and place in which the original bands emerged was transitional not only for music, but for North American cities as well. Sociologically, the musicians and the aesthetics of the Paisley Underground were swept into this changing urbanism. I argue their music and their example heralds the change in indirect and locally suggestive form.

Consider the musicians’ backgrounds. Most were late-baby boomers born in or shortly after 1960, a few like Sid Griffin and Three O’Clock drummer Danny Benair a little older. Many were born and raised in and around L.A.: the westside (Hoffs and the Roback brothers), the San Fernando Valley (the Peterson sisters, Benair), the South Bay (Quercio), and other locales of the polycentric metro area. In publicity, the Bangles have made plain the archetypical suburban childhood experience — being chauffeured in the backseat of their parents’ cars — through which they and likely other Paisley Underground peers encountered the music that inspired them. Inducting the Zombies into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, Susanna Hoffs stated evocatively, “I’ve loved the Zombies for as long as I can remember. I first heard them when I was very a little girl in the 1960s — in the backseat of my Mom’s station wagon — and though their music played through a tinny car radio, its elegance, soulfulness, tonal textures, and foggy London intrigue, found me on the sunny palm-lined streets of Los Angeles” (quoted in Blistein and Exposito 2019). Her experience illustrates a cultivation of musical exploration and affinity from a distinctly suburban vantage point.

Consider also these musicians’ middle-class origins, as retroactively recalled by Sid Griffin: “This is a horrible thing to appear in print, but most of us had pretty decent backgrounds, so there was no cultural or economic status that on a personal level had stung us so much that we wanted to bite back against society” (quoted in Hann 2013). Hoffs, Griffin, Quercio, The Dream Syndicate’s Karl Precoda, and the entire Rain Parade attended college; as noted earlier, Steve Wynn was in a UC Davis band with Kendra Smith and two members of True West, before transferring to UCLA. Griffin’s confession notwithstanding, no vulgar equation of musicians’ socioeconomic status to their inclination to social protest[1] is necessary to consider the educational attainments across many Paisley Underground careers. From the previous section, it’s also worth recalling how some groups trafficked in academically acclaimed literary and visual traditions. Whether learned in classrooms or acquired autodidactically, these young musicians developed aesthetic dispositions that rely on deployments of high cultural capital (Bourdieu 1986).

This point illuminates a commonly-cited aspect of Steve Wynn’s biography in accounts about the Paisley Underground: his taste-making background as college radio DJ, record store employee, and record critic. As he told The Guardian:

With this scene happening, everyone wanted to get involved. And the fact we were making a kind of music we’d been missing means most likely other people had been missing it too. And people who wrote about music or worked for labels had cool taste — maybe they were forced by economic reasons to write about or sign music they didn’t like, but at heart they liked the kind of music we were doing. We were a critics’ band from the start, because critics generally have good taste. You get into that world because you love music. And the Dream Syndicate and the Paisley bands were for people who loved music (quoted in Hann 2013).

Wynn’s statement suggests how the social innovations of the Paisley Underground to the city lie not only in the manifest sounds of its recordings and live performances, but also its participants’ self-conscious appraisal of what underground rock lacked at the time, and how their bands might fill that void. The cultural capital expressed in the musical agenda which Wynn assigns to the Paisley Underground draws not upon institutional credential[2] but the rearticulation and revalorization of then-unfashionable sounds and sensibilities associated with rock criticism and hip record stores. The discerning appraisal on behalf of “people who loved music” and other audiences is the signature task, Bourdieusian sociologists contend, of cultural intermediaries: those who “construct value, by framing how others — end consumers, as well as other market actors including other cultural intermediaries — engage with goods, affecting and effecting others’ orientations towards those goods as legitimate — with ‘goods’ understood to include material products as well as services, ideas and behaviors” (Smith Maguire and Matthews 2012, 552). Although cultural intermediaries occupy formal music industry sectors like record labels, concert booking, broadcast media, and music journalism, Wynn highlights his own DIY contributions as a former critic-cum-frontman of a “critic’s band.”

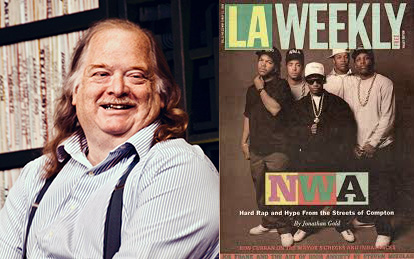

Fast-forwarding to the Paisley Underground’s postscript, some musicians resumed their formal higher education; a few (Piucci, Precoda) eventually took up academic careers. Others found work in music publishing (Benair) and film-TV soundtracks (Hoffs), two niches of the entertainment complex that grew after the Cold War to eclipse aerospace-defense as the L.A. region’s dominant white-collar sector (Scott 2000). By the 1990s, cultural-design sectors in the region advanced beyond products made in L.A. to include those made of L.A., through high-end craft sectors like industrial design, apparel, and automotive design seeking to incorporate the city’s fabled postwar spirit — the openness to popular innovation, youthful rumblings, and multicultural offerings, echoed in the permissiveness of the warm sunshine and unguarded self-displays it affords (Molotch 1996). By the century’s end, similar reflexive incorporations of the L.A. spirit would inform renewed interests in bygone pastimes (e.g., the swing revival) and neglected traditions (fine art and public space, both embodied in the grandiose Getty Center, est. 1997). The region’s culinary milieu especially flourished in the 1990s, as ethnic cuisines and food trucks once confined to immigrant neighborhoods and swap meets found new diners eager to eat their way through L.A. These diners’ pied piper was the late Jonathan Gold, the influential newspaper/magazine food writer and, perhaps not coincidentally, a former musician and music writer. Gold (2000, vi-vii) celebrated the city’s culinary geography in neo psychedelic terms:

What I’m trying to say, I think, is that the most authentic Los Angeles experiences tend to involve a mild sense of dislocation, of tripping into a rabbit hole and popping up in some wholly unexpected location. The greatest Los Angeles cooking, real Los Angeles cooking, has first a sense of wonder about it, and only then a sense of place, because the place it has a sense of is likely to be somewhere else entirely.

Delayed by the scars of the 1992 riots, the wave of reflexive L.A. consumption eventually crashed onto urban space itself. In the first decade of the 2000s, middle-class educated residents spilled over in significant numbers from predominantly white enclaves (the westside, Pasadena) and saturated central neighborhoods (Silverlake, Los Feliz) to begin gentrifying lower-income and/or predominantly non-white areas of downtown, east, and northeast L.A. (Williams and Hipp 2022; Lin 2019). Not that the Paisley Underground musicians necessarily participated themselves in this new Los Angeles urbanism. Some stayed put in old neighborhoods, while others relocated to new cities (Steve Wynn to New York, Sid Griffin to London). But this wider change across Los Angeles points to the Paisley Underground’s third “L.A. story”: the sociological significance of the discerning sensibility they modeled in their cultural production. Beyond their given inspirations and musical approaches, the aesthetic swerve that these bands brought to underground rock — suburban subjects discovering and synthesizing overlooked styles that give new meaning to routine lives and create communities of aesthetic affinity — would soon be observed in other cultural domains and, by the new century, the very geography of Los Angeles. Insofar as the Paisley Underground imagines the city, it has done so by signaling, in their music and their precedent, a license for Angelenos to step back from received geographies of space and sound, and to playfully, psychedelically, materialize another city through cultural communion.

This chapter asks readers to consider the connection between Los Angeles and its music beyond urban scenes and lyrical-visual representations. The Paisley Underground offers little in those regards, I’ve argued: too small and insular to constitute a full-blown scene, the bands weren’t especially concerned with referencing their city, either. One suspects the musicians would be contented if the Paisley Underground’s brief, bright moment is remembered for their music alone, a playful celebration of rock’s rich variety and vibrant development at a moment when the energies of Los Angeles rock seemed compartmentalized into the music industry, youthful turf battles, and esoteric score-settling. Yet behind this aesthetic purity lies a deeper musical contribution of the Paisley Underground: a self-conscious, tasteful intervention to redirect the purpose and evolution of rock by recalling and synthesizing music history into a distinctly contemporary sound. Those are lofty and sophisticated goals. It’s possible the bands of the Paisley Underground didn’t execute them as effectively over their entire discographies as they did with the artistic agenda communicated in early recordings and assorted interviews to rapturous critics, the musicians they inspired, and a cult of committed fans around the world.

The sociological analysis in this chapter gives urban context to this intervention: a collective act of musical and geographical reimagination in a city that was not quite ready for it, if L.A. music over the rest of the 1980s is any evidence. Yet with the following decade, in other cultural domains and then urban spaces of the city, new cohorts of taste-making cultural producers and residential migrants would sustain what the Paisley Underground initiated in L.A. rock: willfully exploring, repurposing, and consuming overlooked styles and traditions to forge elective communities of affinity. To argue, as I do here, that the Paisley Underground anticipated this urban future and articulated its program through musical sound and artist’s statement requires a different analysis of how music imagines the city — one bound less to musicological-semiotic interpretation alone, and attuned more sociologically to broader shifts in cultural agency, social and spatial structures, and urban history.

[1] For instance, Greg Ginn, Chuck Dukowski, and Kira Watt of Black Flag graduated from the University of California, while the Bangles’ Vicki and Debbi Petersen never finished or started college, respectively (Shade 2023).

[2] As best illustrated by the musicology and avant-garde theater training of, respectively, Randy Newman and the Doors, both originally students at UCLA in the 1960s.

ROAD MAP TO THE PAISLEY UNDERGROUND: