A recent study shows that the numbers of dancers, actors, musicians, and other art workers in New York City have declined since 2019, as has the city’s share of the creative economy vis-a-vis other places. The global center of art-culture industries, creatives, and supporters is reaping the consequences of its affordability crisis, and young artists in particular are moving out of the city, or never moving in to begin with. The economic consequences of this decline, for NYC and for arts and culture at large, are profound, but the collective human story — the urban story — is no less critical.

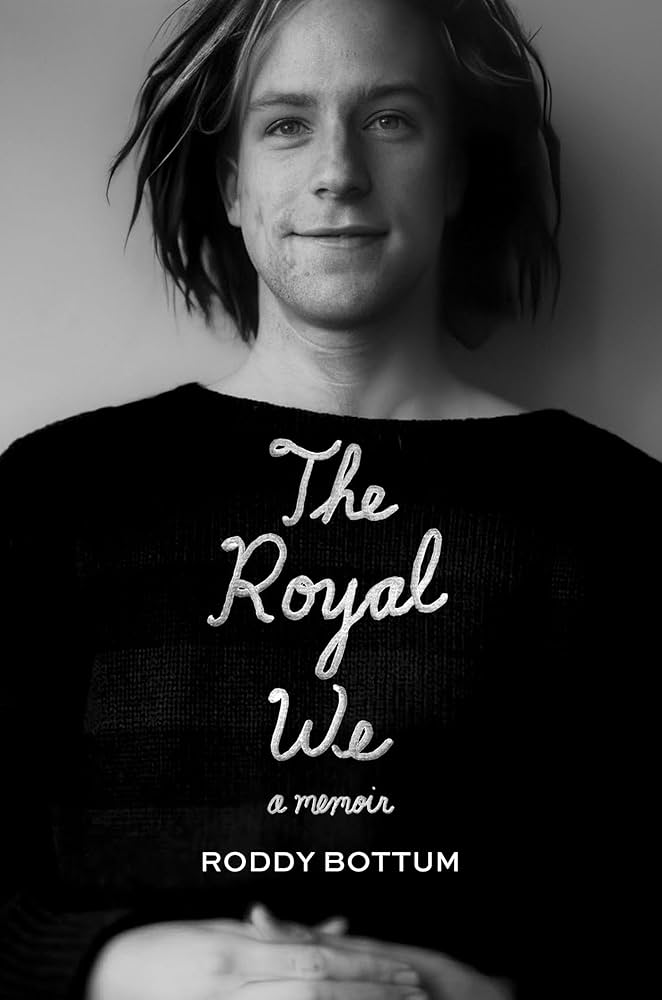

I thought about this while reading Roddy Bottum’s fascinating new memoir, The Royal We. (Caveat: I didn’t actually read the book but listened to Bottum’s narration, which was great.) Bottum is best known as a founding member of the bands Faith No More and Imperial Teen. I forgot how tight he was with Courtney Love, who was one of FNM’s earliest, un-recorded singers, and this book adds insights into the Kurt & Courtney saga of the 1990s. But The Royal We is most valuable as one person’s journey through 1980s underground San Francisco, a world I occasionally saw in my own youth from a distance — the post-punk, pre-email milieu of Frightwig and Survival Research Laboratories, when the city’s civil libertarian ethos mixed with its cultural chip on the shoulder (against suburbia, Los Angeles, puritanical scolds and authorities) to light a bonfire of freakishness, bad attitude, and self-destructiveness. And of art, be that the primary purpose for living in SF or, in Bottum’s case, an unanticipated consequence.

I saw Faith No More in concert twice, the first time in San Francisco, 1986, the second in Goleta, 1993. That first time made the stronger impression, for one reason because they were sandwiched between Hüsker Dü and openers Camper Van Beethoven. FNM confused and even shocked me, their unprecedented mix of genres (hip hop, metal, funk, glossy keyboards, the Nestles Alpine White jingle) not offering an easy aesthetic agenda, their power and violence — drum sticks splintering and breaking, the bassist smashing his guitar on the floor, the drunken Chuck Mosley an effigy of the band’s volatility — making for one bad trip. They were like nothing I had heard before, and frankly nothing like the musically tighter, commercially successful band fronted by Mike Patton that I saw seven years later.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=huicM5dOhFo

This, readers learn, was the early Faith No More’s objective: contrasting genres and musical approaches brought together by dreadlocked post-punks in intuitive pursuit of spectacular nihilism, postmodern irony, and audience confrontation. Bottum, originally a housemate to bassist Billy Gould, was invited into the druggy jams that laid the musical foundation which FNM Mk. 1 (the nomenclaturally punctuated Faith. No Man.) finished with a forgotten, ill-suited singer in a grimy rehearsal space:

We all supported their band. We were devoted to holding up our own and championing our people. We would put up all the flyers for their shows with staple guns and masking tape on telephone poles, on bulletin boards, near the doors of cafes. We told our other friends about the band and went to the shows enthusiastically. There was a tone shift in the village and we were part of it. Punk rock had happened and collided intensely with the hippies, but a new movement was taking hold. It was a darker sound, heavy, slower, rhythmic, tones of death, decay, disparity. It looked it. There were mostly black clothes, some white face paint, you could call it goth, looking back on it, but we didn’t consider it. Swaddles and textiles of the street, we spawned from what the city was. There was rain, there was gray, there was angst and anger toward the random responsibility of fronting a generation, there was art school, there was graffiti and things that combusted magically out of nowhere.

Faith. No Man. took leads mostly from English bands like Joy Division and Killing Joke. The pummel and feel of that band particularly. Mike, the drummer, was listening to African rhythms, studying specifically that at Berkeley. From there the door opened to Jamaican dub. That became a sound that we’d listen to as a household. As we continued making music in the house, we tried to replicate the sounds we were hearing. Billy bought an Echoplex, a tape delay machine, from somewhere, the analog echo was everything. It opened up the world of soundscape and atmosphere to us. I had an ear for short melodic statements that started as spouts of sarcasm in that dark musical realm but always rang clear and stuck in my head when I walked away. Buoyant and optimistic did not belong, and I embraced that dichotomy. Forcing what didn’t belong. Accentuating the loudness of the presentation of song in a world that wanted to be intense. It was always like an inside joke. I could let laughs happen, but inherently, intensely, I clung to the presentation of melody, citing it as my own.

The Royal We reports Bottum’s eventual formal entrance into Faith No More less as a biographical milestone than as a small moment in a wider, environmental process found throughout San Francisco in the early 80s. (Really, look elsewhere for the full Faith No More story, which Bottum drops around the recording of 1995’s King For A Day… Fool For A Lifetime.) This collective process, referenced by the memoir’s title, involves introduction and immersion into a subcultural “village” alongside characters who were unique to San Francisco at this time but no doubt familiar from urban bohemia in other times and places:

The bearded man marching shirtless up the steepness of Market Street above Castro in denim and shorts, always with the red socks; the older identical twins in their sixties, still dressing alike, shopping in Union Square or poised sculpturally side by side on a bus bench; the elegant, well-dressed gentleman with a deep tan and thick head of hair sitting crossed-legged, screaming sporadically as the visitors wait in line to board the first cable car at the start of Polk Street; Bambi, Ginger, Dirk, and Tall Paul; Lucifer, Pineapple Head, Carmen the stripper, Cecilia, and Stupid Saul. On and on and on and on, I eventually became one of them, a consuetude among others, an ingredient in the mix, recognizable and regular, a stitch of the fabric, a piece of the quilt. Back when I arrived, though, I knew nothing, and it took forever to become who I was.

Through evocative language that unfolds pleasurably, The Royal We captures the emergence of what urban cultural scholars like Giacomo Bottà call a structure of feeling — the socially constructed ethos of a time and place that frames the actions, meanings, and institutions of its participants — that is distinctive to San Francisco’s underground at this time but, again, recognizable to dissidents, posers, strugglers, and yes artists in cheap cities elsewhere.

Beer bottles and a spilled bong, dirty plates and forks, magazines and flyers and ashtrays everywhere, never furniture, only mattresses or futons in our individual bedrooms. Some had sheets, some simply sleeping bags, pillows uncased and stained. An eventual red kitchen table we bought at Thrift Town, two chairs and two milk crates we’d sit on, one bathroom we’d share, our toothbrushes mingled in a dirty mug on a sink next to a bar of soap that would move to the shower and back to the sink. A black oversized plastic bag sat full with our trash in the smelly alcove at the back of the apartment. A turntable and speakers in the fireplace of the living room and stacks and spreads of records, fanned out, covering the floor.

Our rent for the flat was $160 apiece. Burritos were two dollars. Eating half, we’d save the second half for tomorrow. Fold the aluminum foil around the stump of it and put it in the refrigerator. At night we’d drink cases of cheap Brown Derby beer that we’d carry home in boxes from the big supermarket. We’d steal meat when we could and cook big steaks in a cast-iron pan. The fire alarm would go off, we’d disconnect it and get drunk in the smoky haze and piece together the puzzles on the insides of the caps of the beer. The world and us in it was wobbly and hilarious, there wasn’t a time when we weren’t arguing or laughing.

There is nothing strategic or even reasonable about the formulations of this structure of feeling. As The Royal We documents, it swept up many into addiction, precarity, or death — so many that some might say it’s just as well the structure of feeling is now extinct. Still, it shaped Faith No More at its most potent and rawest, and it informed the perspective that Roddy Bottum carried out of the band, into the queer alt-pop of Invisible Teen, and onto a final farewell to San Francisco:

The fog in the village grew denser and thicker till no one could see a thing, not three feet in front of them. The smell of rot set in and all conversation stopped. A collection of elders remained but their voices were ignored as the village around them crumbled into something new. The cold white blanket, wet and heavy, smothered all that had been. The music stopped and the children died. In its place was the glorious Internet and all that it brought. The ease of life. The casual and specific luxury of getting answers with the wave of a hand. Button-down boys with their juju-bead bracelets eating peanut M&M’s, strollers and strollers and half-drunk women talking loud, cars replacing bikes, eventually driving themselves. What was the point of reading or listening with your ear to the ground when the death of the village had already been decided? The only thing left to hear was the slowing of the pulse, the sporadic heartbeat that finally stopped. Smell and taste and tactile fruition took a backseat to a pertinence of poison in the new industry. Goodbye, fuckers. I will always hate you.