[Published in Contemporary Sociology 53.4 (July 2024): 341-343.]

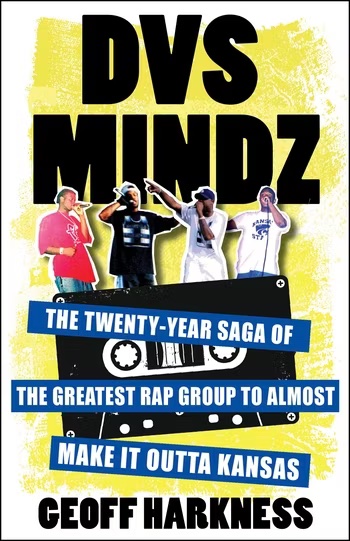

DVS Mindz: The Twenty-Year Saga of the Greatest Rap Group to Almost Make It Outta Kansas, by Geoff Harkness. New York: Columbia University Press, 2023. 406 pp. $28.00 paper. ISBN: 9780231208734.

Leonard Nevarez

Vassar College

lenevarez@vassar.edu

How might sociologists engage the music biography genre? Sociologists examine the activities of popular music artists and collectives to study art economies, cultural-media industries, geographical and institutional milieus for cultural production, and the processes by which individuals internalize identities and deploy assorted capitals (cultural, symbolic, social) for situational advantage and socioeconomic gain. Still, the biography genre seems a harder row to hoe, insofar as its popularized narrative form — the dramatic profiling of a subject’s origins, achievements, tragedies, and legacy — draws upon a personalized account at epistemological odds with a sociological imagination. Yet biographical works can shed light on an important concern: the career as outcome of life-course sequence, social reproduction patterns, formal and informal status attainment, and larger contexts that enable and constrain advance through social fields.

Geoff Harkness threads these needles insightfully if lightly in DVS Mindz, the story of the titular rap group whose lyrical skills and pioneering of the Topeka, Kansas rap scene likely remain unknown to even ardent fans of late 1990s/early 2000s hip hop. Righting this music-history wrong is the author’s primary goal, undertaken in an accessible work that sandwiches the group’s lifespan between extensive account of its members’ lives before and after. For reasons that may puzzle his fellow sociologists, Harkness hews to strict narration and “offer[s] no theoretical explanations of any kind” in writing the lives and music of his subjects. “The biographies of Jay-Z and Led Zeppelin do not cry out for theoretical analysis, and DVS Mindz’s story does not either” (pg. xxiv). Still, DVS Mindz offer something of value for sociologists: a thickly reported case of career failure by an innovative and charismatic musical group operating in a field at a transitional moment.

Not just a true believer of these obscure legends, Harkness was a friend to DVS Mindz, an occasional paid collaborator on their promotional videos and publicity, and a participant in the music scene that straddles the Kansas-Missouri state line, thanks to a writing job at a Lawrence, Kansas, arts-and-entertainment weekly that he held during graduate school. While penning local reviews and interviewing numerous acts from hip hop, alternative rock, and punk over 2000-03, Harkness accumulated hours of video interviews with DVS Mindz that provide the data for the book’s middle section, written in the present tense of their artistic and commercial heyday. This section skillfully captures an era of musical context — cigarette smoke-filled nightclubs, DIY record labels and CD manufacturers, local music publications and their annual entertainment awards, independent music stores and chain retailers — that is largely extinct in contemporary popular music ecosystems. Also gone from the scene is DVS Mindz’s energetic, streetwise style of “cipher”-based rap (which stresses individual lyricism and dialogical rapport) that made for dazzling group performance and a capella solo flights before hip hop shifted to emphasize sing-along “hooks,” nightclub “bling,” and dance rhythms.

The book brackets this heyday with sections devoted, respectively, to three background decades and two decades of career postscript, as conveyed in retrospective interviews that find members at an older age and in a more reflective mindset than the youthful bravado of their lyrics. Opening chapters describe family breakup, parental neglect, and substance abuse that push the future rappers out of public school and into parental responsibilities, incarceration for some, and economic precarity — circumstances that are familiar in street rap lore (not to mention the sociology of poverty), if rarely from a Topeka vantage point. These conditions also bring the quartet together when they room together in an unsupervised house (inherited after a parent’s premature death), where they share food, beer, and weed and develop their rapping style. If not yet as a payday, hip hop feeds the young DVS Mindz as therapeutic release and a basis for elective household. “A lot of us was going through shit where our family families, we couldn’t contact them, or we were going through shit where they didn’t want to be bothered or they wouldn’t understand,” one member explains (pg. 51). “So we made our own family.”

Particularly intriguing is the book’s final section, which follows the group through interpersonal acrimony and adult pivot. Whereas rap lyrics and pop music scholars have long observed that commercial success is a more legitimate concern for rappers than for musicians in rock-based undergrounds, Harkness documents how its pursuit proves too burdensome for a band with children to support and years of musical hustle to recompense; the demand to know “where’s the money” that should have accompanied their regional acclaim poisons the band against their friend-turned-manager and, eventually, each other. Too late for DVS Mindz, the advent of cheap home-recording technology allows the older musicians, by then supporting themselves outside of rap, to record solo music and recommit to a “pure” artistic identity. With poignancy and nuance, Harkness revisits the members as they redefine their adult identity along diverse post-group paths; jail, recovery, community college, and company ladder. (One member’s reconciliation of his Black Lives Matter solidarity with voting to re-elect Donald Trump in 2020 should be required reading for Democratic Party strategists.) At the story’s end, DVS Mindz bring three of the original four members back for a reunion album that hides in plain sight on streaming platforms which comprise rap’s current commercial battlefield.

As a music biography, DVS Mindz may not burnish the legend of its subjects as effectively as Harkness wished. In its emphasis on personal perspective and local circumstance, something had to give way in the book: a fuller contextualization within the history and aesthetics of rap music. Readers are expected to know their own way through the aesthetic shifts that accompanied the band’s lifespan, from the metaphoric play and minimalist rhythms associated with Rakim and other East Coast icons into the explicit violence and immersive tracks of gangsta and horrorcore styles. Oddly, given the high regard that Harkness has for these rap lyricists, his book reprints almost no DVS Mindz lyrics; this decision may serve to correct for his subjects’ self-mythologizing and to foreground a distinctly sociological emphasis, but it leaves readers still wondering what musically distinguishes this group.

As a work of sociology, DVS Mindz attests to the empirical richness and analytical stimulation of the popular music biography genre. DVS Mindz adeptly illuminates the worlds of Black youth, poverty, and popular culture that receive regular albeit one-sided reporting in rap lyrics. More abstractly, its career scan contrasts usefully to conventional sociological inquiries into music genre, scene, and industry, which by their cross-sectional design tend to reinforce the common view of pop-music as a young person’s game. Certainly, Harkness’s argument that career failure is a more “universal” outcome than the successes and influences documented in most biographies is intuitively persuasive. DVS Mindz can methodologically stimulate and sit well within larger archives of biographical accounts, as a case for small-N analysis to illuminate artist variation in background factors, industry characteristics, and cultural domains, although this analytical purpose must necessarily be activated by other scholars.