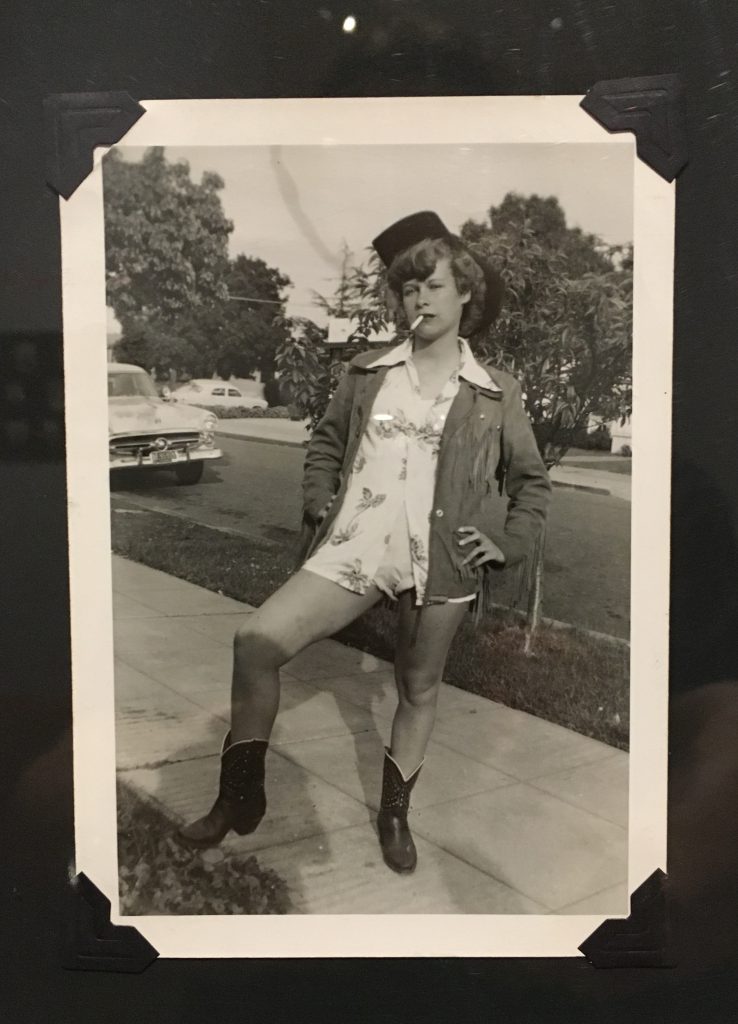

One of my most exciting and challenging writing assignments is now available. I was asked to write 150-200 words of text to accompany a photo featured in Other People’s Pictures: Snapshots from the Peter J. Cohen Gift, an exhibit that just opened at the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center at Vassar College. Here’s the picture I chose and the text I wrote:

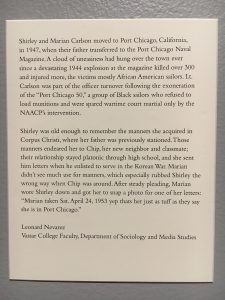

Shirley and Marian Carlson moved to Port Chicago, California, in 1947, when their father transferred to the Port Chicago Naval Magazine. A cloud of uneasiness had hung over the town ever since a devastating 1944 explosion at the magazine killed over 300 and injured more, the victims mostly African American sailors. Lt. Carlson was part of the officer turnover following the exoneration of the “Port Chicago 50,” a group of Black sailors who refused to load munitions and were spared wartime court martial only by the NAACP’s intervention.

Shirley was old enough to remember the manners she acquired in Corpus Christi, where her father was previously stationed. Those manners endeared her to Chip, her new neighbor and classmate; their relationship stayed platonic through high school, and she sent him letters when he enlisted to serve in the Korean War. Marian didn’t see much use for manners, which especially rubbed Shirley the wrong way when Chip was around. After steady pleading, Marian wore Shirley down and got her to snap a photo for one of her letters: “Marian taken Sat. April 24, 1953 yep thats her just as tuff as they say she is in Port Chicago.”

This text is a work of fiction, a far cry from the standard writing of a sociologist but what the Loeb Art Center curator Mary-Kay Lombino asked of the artists, professors, and students she solicited for this exhibit: “The text should be a musing on what might be happening in the photo (situation, setting, event, etc), who might the subjects be, and or who might the photographer be.” Having attempted sociological fiction only once before (in this blog post), I was eager to use this opportunity try it again. I know writers aren’t supposed to reveal ‘what they were trying to do’ in their writing, but as a statement of methodological reflexivity I feel I should anyway.

When I was given the opportunity to browse the approximately 500 photos that would be donated to the Loeb Art Center collection (from which a subset are now on the gallery walls), I was disinclined to use mere fantasy to enliven or enlighten the work. I was particularly cautious given the collection’s thematic focus on gender; as a straight white man, I didn’t want to simply reproduce a male gaze onto the subjects of these snapshots:

Mr. Cohen has amassed more than 35,000 amateur photographs culled from antique shops, flea markets, private dealers, and on-line sources. Most of the photographs are anonymous and capture moments in the lives of ordinary people, often depicting celebrations, vacations, and gatherings of family and friends. Individual images were chosen for their eclectic, idiosyncratic, sometimes humorous nature as well as for their subject matter, with a particular focus on the lives and activities of women.

So I gravitated to any contextual clues I could find among the photos themselves or written on the back. This photo made it easy, with a penciled caption on the back that I could work from: Marian taken Sat. April 24, 1953 yep thats her just as tuff as they say she is in Port Chicago.

My research began by Googling “Port Chicago,” a place I had never heard before. Expecting it to be some port on Lake Michigan, I was surprised to learn it was a naval installation located deep along the San Francisco Bay, where it starts to become the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta. Even more startling was the first Wikipedia entry that appeared: Port Chicago disaster. I had never heard of this episode of racial conflict and wartime panic before, and provoked by its invisible connection to this apparently carefree image taken nine years later. I tried to imagine what indirect relationships Marian might have to that episode and to what must have been a formidable effort at Port Chicago to contain and suppress this controversy.

As a military brat myself, I also resonated with the display of “tuffness” Marian is making for the camera. Those are some short shorts for 1953! And that’s a peculiar set of western clothing she’s wearing, more likely acquired on cross-country drives between her father’s stations than from personal experience with cowboy life. Marian’s presentation of sexual independence suggested a potent intersection of gender, class, and race for which I imagined a possible scenario: a triangle between Marian, her sister the photographer, and Chip, the neighborhood boy carry a burden of patriotic duty and wholesome masculinity on his shoulders.

In less than 200 words, I wanted to propose that this backstory might stand in for an insttutional erasure of the black sailors’ struggle. The connection I chose, perhaps obvious but still poetic to a sociologist, was C. Wright Mills’ contemporaneous The Sociological Imagination; the phrase I used, “cloud of uneasiness,” references this passage from the first chapter:

My thanks to Mary-Kay Lombino, curator at the Loeb Art Center, for inviting me to participate in this exhibit. It runs through September 17 at Vassar College. Click here to browse more of Peter J. Cohen’s collection.