[Presented at the University of Toronto Department of Sociology on May 1, 2015. Thanks to Judith Taylor and John Hannigan for this opportunity.]

It’s a pleasure to speak today on a new research project I’m working on. In anticipation of this talk, I had a couple of other topics I could have lectured on with more authoritative findings. By contrast, this is the very first talk I’ve given on this subject, it happens at one of the earliest stages of the project, and it involves a multidisciplinary approach that pulls me out of the sociology I was trained in. But I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to present this project to a Toronto audience because the subject comes from Toronto. So I hope you’ll help me think through some of the questions I’ll be raising and some of the Torontonian aspects of this material.

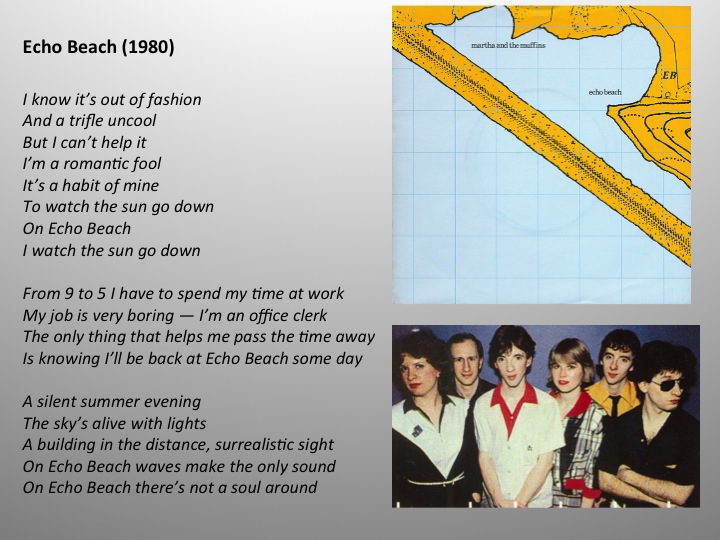

Martha and the Muffins were a band that formed from a group of OCA students back in 1977. They played in the city’s punk and new wave scene that was centered in the Queen Street West neighborhood then had an early, transatlantic hit that pushed them to very top of Canada’s new wave groups. They weathered a name change, record label changes, departures of band members and stuck it out through 1992. The band’s principals retired into Toronto life and resumed activity rather recently, releasing a new album a few years back.

Let’s listen to that big hit:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iPPUCOUDuyIThis was sung by the two Marthas, Johnson and Ladly, but written by Mark Gane, the Muffins’ guitarist — a reminder that the perspectives heard on these songs, and in music in general, are enacted in performance as much as they’re composed beforehand. “Echo Beach” is said to be inspired by Sunnyside Beach on the shoreline of Lake Ontario, back when Mark held a day job as a wallpaper inspector in a paint factory (he obviously changed the occupation in the lyrics).

“Echo Beach” is an excellent calling card for the band. It introduces themes that recur and evolve across their career: everyday alienation, a dreamlike state or setting, and the projection of these countervailing impulses on geography and place. “Echo Beach” features the group’s early sound which falls squarely into the classic new wave format: the live sound of guitars, bass, drums, keyboards and sax. Consequently it sounds a little dated compared to recordings they would make just a couple of years later. On the other hand, there’s some really nice touches here — the strobing keyboard at the beginning, the fact that there’s no conventional chorus until the very end. There’s also a very interesting element of gender and performance, which I’m happy to talk about later.

I’m going to lay my cards on the table and say that Martha and the Muffins were one of the best, most interesting, and certainly most underrated groups of the new wave era. I don’t think I’m alone in this assessment; as musicians and music historians have turned their attention to new wave and postpunk music over the last decade or so, the spotlight is turning back toward Martha and the Muffins ever so gradually.

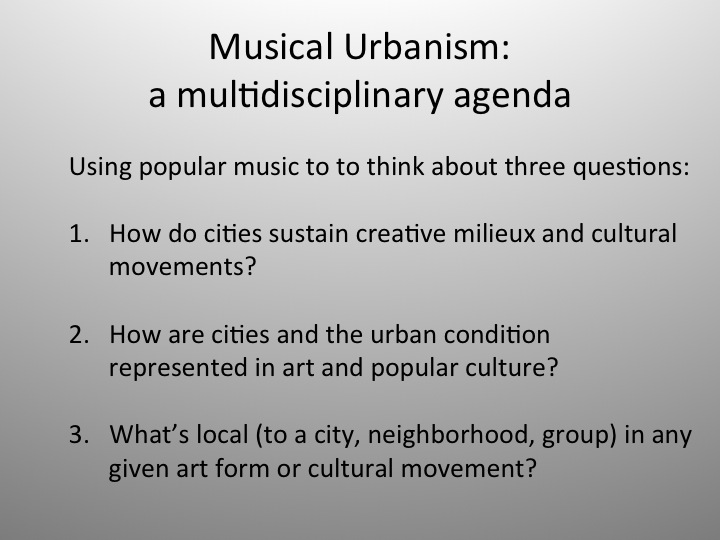

So I come to this as a fan, which is a new angle for me as a scholar. But Martha and the Muffins present issues of scholarly interest, which I frame through a multidisciplinary agenda I call musical urbanism. A word about that:

I was trained as an urban sociologist, and my work originally used urban political economy to analyze the politics of urban growth and of place consumption that drew upon natural amenities and urban vitality. This work was never primarily cultural in its analysis.

I’ve recently come around to studying music as a project in urban cultural analysis — music in, of and about cities. In sociology there is great work in urban cultural analysis that I draw on, but this project is maybe more influenced by my participation in the multidisciplinary program of urban studies at Vassar College. I’ve been very lucky to have colleagues and co-teachers with backgrounds in American studies, literary theory, and media studies among other fields. I’ve learned a lot from my exchanges with colleagues and students, starting with the way that humanists across several disciplines think about the cultural artifact — about the text.

They dwell on the specificity of particular ‘works’ in a way that sociologists traditionally don’t. Our disciplinary inclination is to view artifacts as part of larger groups and categories of social phenomena, be that networks of far-flung actors and historic contingencies (in the Becker “art worlds” tradition) to emblems and occasions for solidarity and resistance (in the social movement and cultural studies traditions). Those are important perspectives, but they tend to support an instrumentalist perspective that I find can void the work — in this case, music — of its expressive and media specificity.

This may be one of the key philosophical divides between the sciences and the humanities. And of course it’s recapitulated in urban studies, where there are traditions and audiences interested in specific cities, and others want a more comparative or universalistic takeaway. So my work in musical urbanism involves, first, exploring the interstices of these disciplinary divisions, and the question of urban/historical/cultural specificity.

Second, much of my work in this field — various essays and blog posts, and increasingly some talks and publications in the field of popular music studies — has focused on musicians. And not just your typical musician, but the ones who have gone on to some repute and social significance through recordings, performances and influence. So I’ve written at length on UK groups Joy Division and Simple Minds, the Los Angeles musician/actor Tito Larriva, or an entire cohort of mixed-gender groups that I’ve categorized under the label “new wave rent party” and begun to tease out what’s ‘urban’ about their work. This Martha and the Muffins project began this same way.

These musicians generally come from the postpunk and new wave genres of the late 70s and early 80s. And if I can be accused of bringing a certain generational baggage to this project, then I’m probably guilty as charged. But one thing that studying musicians of this age and older permits is to observe the arc of an entire career.

This means I don’t limit the analysis to musicians, typically in their 20s and 30s, at the peak of their commercial and cultural relevance. Contemporary “relevance” tends to be the starting point for a lot of music writing. It also tends to be a common focus in creative city research and policy focusing on independent and underground music scenes; as that research suggests, pop music is a young person’s game, for one reason, because musical careers are filled with risk and put a premium on labor-market “flexibility.”

By contrast, taking in the broader course of a career lets us examine how careers evolve as contexts change, as opportunities emerge and disappear, and as audiences and aesthetics shift. So my research refocuses the cultural object under study from the specific work to the creative career. A question that interests me then is, How do musical careers evolve in place?

This is a question that the case of Martha and the Muffins is well suited to illuminate. They grew up in Toronto’s suburbs, formed around the OCA, were darlings of the Queen Street West scene, and after a career that included a couple of years based in England, they came back to Toronto. And the music industry has evolved such that they’ve acquired the rights to many old recordings and now live to a considerable degree off repackaging and reissuing their recordings on independent crowdsourcing platforms.

A point to clarify when I say they’re a ‘Toronto group’: In music journalism when you read about Martha and the Muffins, they’re invariably preceded by the label “Canadian.” There’s a corrolary in most scholarly references you see to the group: Martha and the Muffins are said to be interesting because they speak to a distinctly Canadian experience. As an American scholar, I’m coming up to speed on this tradition in Canadian criticism and cultural studies, but I nonetheless proceed on the premise that what makes Martha and the Muffins a useful case is not their Canadianness. The metropolis is more helpful for understanding a musical career in place.

In that regard, how has metropolitan Toronto worked for them over the course of their career? The conventional wisdom on metropolises, at least thriving ones, is that it’s their diversity of economies, neighborhoods, housing types and land uses that make them a place for all seasons in the lives of their populations. There’s some simplification here, of course; such a functional ecology presumes effective transportation systems for maximum circulation; otherwise, it may be most accessed by a middle-to-upper socioeconomic stratum.

But this axiom seems to apply to Martha and the Muffins. They had a thoroughly middle class background: they grew up in suburbs like Thornhill and Etobicoke; they attended art school in downtown Toronto. They played the clubs and drew upon the music industry clustered in the city. Now, they’ve settled down now to quiet bohemian lives in Riverdale. Is metropolitan Toronto simply a functional setting for the group?

Answering this question motivates my work at this early stage of the project. To illustrate some of the theses I’m pursuing and refining, I want to play five recordings from over their career. As we observe again the recurring themes of alienation, surrealism, and place, think about how those themes develop and how the metropolis serves as a context for that development.

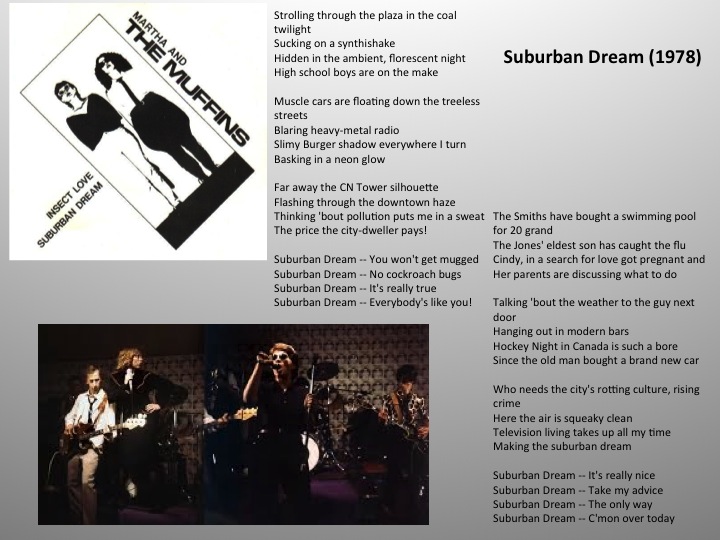

One of the earliest recordings from the band, “Suburban Dream” offers a very sarcastic, caustic take on suburban life. There’s not much empathy for suburbanites, despite the “we” of the lyrics. The real collective signaled by that “we” is likely fellow college students and other middle-class exiles living then like the band in inner-city Toronto. This is a party song, you can dance and sing along to it, and its simplicity makes some sense in that context.

“Saigon” is promotional single and a stand-out track from their first album, in part because it features Martha Johnson’s Ace-Tone organ so prominently. The use of keyboards to create jarring tones was common in new wave — think Elvis Costello & the Attractions or the B-52s at this time — but Martha generates a distinctively eerie, reedy tone that creates a hypnotic mood not a million miles away from Pink Floyd.

As for the lyrics, I don’t know if anyone in the group had ever visited Saigon, but that’s not the point. These lyrics evoke a daydream or fantasy set in an exotic, spectacular place. I like the jaded emotion behind the lyric, “Drinking absinthe till dawn.” For a group of white middle-class Torontonians who weren’t known for living dissolute lives, what’s significant about Saigon is that it’s somewhere else in contrast to where they came from.

1981’s This is the Ice Age, their third album, is arguably the best Martha and the Muffins record; it’s definitely the major transitional work for them. The group was becoming reformulated with Martha and Mark, who were now a romantic couple, emerging as the bandleaders; they had a new manager who shielded them from an unsympathetic record label; and they began working with a new producer, Daniel Lanois, the brother of new bassist Jocelyne who was then a relatively unknown quantity working out of his home studio in Hamilton.

“You Sold The Cottage” is a deceptively conventional band recording for an album that elsewhere puts texture, sound collage and long stretches of beatless, ambient music front and center. The lyrics revisit and relocate the childhood experiences first introduced in “Suburban Dream.” We’re now in the lakeside beaches and vacation cottages of rural Ontario where as children their families summered. IThis was a conspicuous if not standard amenity of middle-class Toronto life at the time. There’s a note of ambivalence here that contrasts with the unambivalent sarcasm from “Suburban Dream”; we detect a melancholy that the cottage of childhood has been sold, even if those family trips were most memorable for the insect bites and critter attacks.

Two things to notice: first the coda features this beautiful piano passage suspended above this syncopated beat, where Martha recites a list of place names. Her phrasing and pacing are really exquisite: there’s a Proustian recollection of bygone time and setting that’s quite moving. Second, that bizarre opening melodic figure is the sound of all the instruments alternating their lowest note with their highest notes. It’s a clever way to represent the pull of dialectical forces; the song emerges out of the middle from these two opposing tones.

This is the title track and promotional single from their fourth album. The city is depicted rather generically, its particularity having been transcended, while the lyrics evoke a Simmelian condition of urbanism: a search for interpersonal connection and commitment across the city’s social and spatial distances. This sense of modern disconnect is a familiar theme in postpunk, and to that end this track does use the machinic rhythm that’s almost postpunk cliché to evoke a cold, mechanical world. But it also has a mysterious quality with the beds of keyboard swells and leaving a large space in the middle of the sound.

This is a characteristic example of the group’s surrealistic vision. The spaces and functional separations of the metropolis seem to fade until discrete spheres of everyday life sit atop one another, mystifying and enchanting the everyday codes that animate the metropolis.

With this track, we’re now fifteen years into the group’s career. This is from the last album Mark and Martha recorded before they took an eighteen-year break to raise their daughter in Toronto. They had just returned from two years in Bath, England — their only substantial period of residence outside Toronto, which they had first visited during the recording of a prior album. Incidentally, at that time Bath had just been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site to acknowledge and preserve its history of architecture and landscape design. That landscape sensitivity and ethos of preservationism appear very pointedly in this track.

The old Toronto of their childhood is evoked once again, now from a sentimental perspective of what has been lost to thoughtless development and change. The song has a plaintive tone epitomized by that mournful violin — a new instrument for the group, of a piece with the contemporaneous turn to Canadian folk in the country’s pop music. If the subject of the song isn’t clear enough, an accompanying video shows vintage photos of old Toronto places and life held up against backdrops of what remains of those places.

As this last track suggests, it’s possible to see a history of pre-amalgamation metropolitan Toronto from this playlist. I would caution against a simplistic reading of history and place from this music, however, because history doesn’t imprint itself immediately upon creative work. Toronto is mediated here via the intervention of the creative representation and, to turn specifically to the biography of this group, via the experience of alienation in place and of place.

In social research, creativity is often addressed in terms of process — through the work of Richard Florida and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, as interactional/organizational foundations and cognitive dynamic respectively. I’m trying to think more about its representational quality — by the object it depicts and transforms. The creative representation is necessarily editorial, necessarily selective in depicting its object, so how can we think about the parameters of its selectivity? Specifically, how does the Toronto represented by Martha and the Muffins reflect a real Toronto?

To think about this, I find three analytical frameworks are helpful. The first comes from the late cultural geographer Adam Krims, who offers the idea of the urban ethos. This invites us to think about how representations of space are structured by the range of historically specific urban experiences, both within particular places and maybe more importantly from widely shared discourses of urbanism. The scope of variation in urban representations is constrained by the limits of cultural salience and historic legibility, and is enforced, in the final instance, by audience’s interpretations. And of course, cultural producers are themselves also audiences in this regard; they hail from the same society.

A second framework comes from John Urry’s notion of the Tourist Gaze. Here is another structuring framework for the salience of place, which Urry narrows around the issue of the tourist’s attraction to particular settings and landscapes. In the alienated modern world, tourists find appealing places and landscapes in their contrast with the everyday settings of work and home. That appeal is evident in the travelogues that the band recorded: “Saigon,” other songs like “Luna Park,” “Jets Seem Slower in London Skies” and “One Day in Paris.” The tourist gaze also signals the antithetical places of everyday, which we’ve seen in tracks like “Echo Beach” and “Suburban Dream.” “You Sold the Cottage” occupies an interesting liminal space between these two.

A final structuring context is the life course. At different points in people’s lives, they enter into social relations and social contexts that promote the pursuit of different goals. In the worldviews depicted by this group of very ‘typical’ middle class bohemians, we see the stages of adolescent individuation, education and work, the development of autonomous adult subjectivities through the shedding of old friends and the formation of romantic units, and finally the other-directed sympathies that come with parenthood.

As the life course yield different goals and concerns, so too the metropolis may support different meanings and values. That diversity echoes the idea of the functional ecology of the metropolis, but now it is represented through its experiential opposite, as an ecology of alienation. Thus the representation of social reproduction changes from the banal suburbs regarded with derision to the getaway country viewed with a more nuanced ambivalence. By the time of “Everybody Has A Place,” the settings of childhood become sentimentalized, as the stakes of what has been lost become clear when seen through the eyes of soon-to-be parents.

So this gives you a taste of the material and ideas I’ll be exploring further this summer when I returt to conduct interviews and fieldwork with the principals in Martha and the Muffins. Some questions to conclude upon:

First, is this kind of musical urbanism still possible in Toronto? That’s a question that could be answered with research on contemporary Toronto musicians. But I also have a different issue in mind. It’s been said that alienation is quintessentially a condition of modernity; it’s not germane to postmodern conditions where the center no longer holds, for either the subject or the society. I don’t know if the concept of postmodernity is relevant, but it’s clear the Toronto depicted in the work of Martha and the Muffins no longer quite exists. After amalgamation, the old suburbs have in many cases been absorbed into municipal Toronto, setting off crises of civic and political identity. Arguably much of the cultural innovation is now in the outer rings of metropolitan Toronto, where foreign immigration and a remarkable experiment in high-rise density and infill development are driving social change.

On the other hand, Mark and Martha now lead quiet lives in downtown Toronto reissuing their old releases. With this activity suggesting a music industry analogue to the iconic postcard urbanism that central Toronto specializes in, perhaps their career has entered a postmodern stage.

Second, what are the conditions in which creativity adopts such explicitly spatialized, cartographic and geographic aesthetics? Possibly we can think about this as a generalized Torontonian ethos, perhaps harkening back to Jane Jacobs’ influence or to the neighborhood preservationism that Matt Patterson has written about. But can we model this geographical reflexivity as a more individualized sensibility?

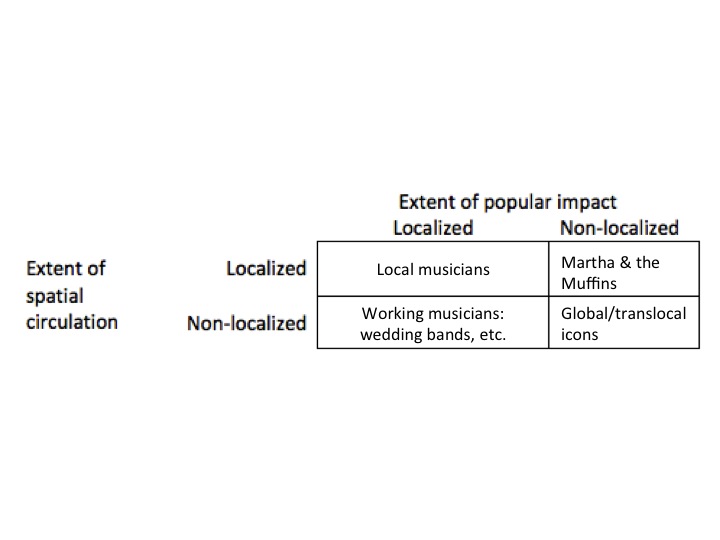

And finally, how might we think of the ‘localness’ of Martha and the Muffins’ career in comparative context? Their Torontonian biography notwithstanding, they’ve had some measure of non-Canadian success. For instance, in 2002, a German record label label commissioned several electronic music producers to remix “Echo Beach” for an album.

This underscores at least two dimensions of spatial circulation — of biography and of cultural impact — that we can depict in a 2×2 table. This is a very preliminary conceptualization, but this materials suggests other frameworks with which to locate the specificity of Martha and the Muffins’ music and career.