The top ten! These are the greatest second chapters, left turns and career reinventions in pop music history. Don’t forget to review how we came to this point…

PREVIOUS:

50-41

40-31

30-21

20-11

10 T. Rex

Glitter rock, the visual appearance of a gay aesthetic in pop music, and the first real ‘sound of the 70s’ can all be chalked up to T. Rex. Yet before they began their hysteria-inducing reign atop the British charts with the late 1970 single “Ride a White Swan,” they were Tyrannosaurus Rex — just another hippie group out of London, and not a particularly distinguished one. Steve Peregrin Took banged the bongos (not a gong), while Marc Bolan strummed an acoustic guitar and warbled his poetry about wizards, unicorns and other fantasy themes. Interesting, but nothing the Incredible String Band didn’t do a lot weirder at the time.

But stardom was always in the cards for Bolan. With the help of producer Tony Visconti (later to work his magic on David Bowie’s recordings), Bolan found an electric guitar, the boogie, and a way to make the little girls and boys squeal with feelings they didn’t know were inside them. The opening chord on “20th Century Boy” still shudders with an audible charge of excitement.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nwOmXMyZXKA

9. Willie Nelson

Willie began his career in the early 1960s as a short-haired songwriter in Nashville, most notably delivering “Crazy” to Patsy Cline. He carved out a decent solo career for himself, but Nashville’s tow-the-line ethos and slick countrypolitan sound rubbed him the wrong way. In 1971, Nelson picked up his middling career, moved to the Texas hill country, and was embraced by the nascent “hippie country” set in Austin. He became the icon of “outlaw country” alongside Kris Kristofferson, Waylon Jennings and others, although none of them had the follicles or cojones to grow their hair into freaky man-braids like Willie.

Today, Willie’s career is the touchstone for every country artist who becomes disaffected by the Nashville machinery; “alternative country” and the city of Austin owe immeasurable debts to his pathbreaking efforts. Willie Nelson was recently seen recording a pro-marijuana song with Snoop Dogg.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eEGgADIUf0g

8. Frank Sinatra

“Frankie! Frankie!!” Sinatra began his career as a 20-something “teen idol” from Hoboken, New Jersey, crooning in front of big bands to screaming bobbysoxers. By the 1950s, his music career appeared to be washed up, as the big band era subsided and a highly processed pop sound (epitomized by Sinatra’s nemesis, producer Mitch Miller) came to the fore. Sinatra evidently took to heart the proverbial advice, “Go west, young man.” His creative rebirth began in Hollywood, first in films: the musical On the Town, followed two highly lauded dramatic roles in From Here to Eternity and The Man with the Golden Arm. Then, at Capitol Records he partnered with arranger/conductor Nelson Riddle on the series of albums on which Sinatra’s reputation still rests. Las Vegas and the Rat Pack beckoned, of course, but Hollywood would witness Sinatra’s final great legacy: his 1960 founding of Reprise Records, which would go on to great heights as an artist-friendly label in the country-rock and singer-songwriter eras of the 1960s and 70s.

7. Tom Waits

When I crowdsourced the question, “Who comes to mind when you think of bands or musicians who reinvented their music/themselves in a serious or surprising way?” Tom Waits was the most popular response. Before 1983, Waits was loose in Hollywood, pursuing a boho jazz schtick. He did it well enough, earning some fame (and, thanks to the Eagles’ version of “Ol’ 55) enough money to waste at the bar for 10 years and 6 albums, but it was winding up an artistic straightjacket.

With his 1983 album Swordfishtrombones, Waits mined an eclectic, anarchic melange of found sounds and old, weird Americana that would mark the terrain for the rest of his career. In fact, the album’s musical distance from the prior record isn’t so vast — Waits’ voice had already evolved into his famous gravelly tone, and there are stark electric blues to be found — but Swordfishtrombones reflected a significant change of scenery (from Vine Street to downtown Manhattan), influences (no wave, Robert Wilson’s musical theater) and characters (his wife Kathleen Brennan). Subsequent Waits records would go even further down this new direction, but the turn toward a new art and new audiences began here.

6. Bob Marley

Marley is the symbol of Third World cultural and political independence, so it’s controversial to assert that any outside collaborator, much less a white “vampire” (in Lee Perry’s notorious assessment), had an undue effect on his career. But Marley’s ascent to global iconicity owes a great deal to the intervention of Chris Blackwell and Island Records. When he signed Marley, already a veteran of the ska and rocksteady eras as a teenager, in the early 70s, Blackwell knew he had a star-in-the-making, but he didn’t want to launch yet another Jamaican recording artist to British audiences skeptical of reggae’s cultural significance. Blackwell exerted a heavy hand on Marley’s Island Records debut, 1973’s Catch a Fire, rearranging and remixing the songs, even adding tracks recorded by R&B musicians in America.

As a result, Blackwell effectively brought the original Wailers to an end and set Marley on a different musical path from the roots reggae styles favored by Jamaican listeners of the time. To be sure, although Blackwell effectively opened the door to rock audiences and critical respect, there’s no question that Marley’s talent and charisma are responsible for how he went about as far as any musician can go. Still,Marley was shrewed enough to stick to the musical template that Blackwell showed him. The great paradox is that Jamaican audiences weren’t all that interested in Marley’s music while he remained alive, even if they embraced him as their national grassroots emblem with a fervor rivaled only by Haile Selassie himself.

5. Carole King

In the years between Elvis and the Beatles, Carole King and her husband Gerry Goffin worked in New York’s Brill Building, turning out the golden oldies of tomorrow while still in their early 20s. With the Chiffons’ “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow” they gave the girl group sound its first #1. They captured the daydreams of working-class New Yorkers with the Drifters’ “Up On The Roof.” And listen to the haunting “No Easy Way Down” on 1969’s Dusty in Memphis and ask yourself if they didn’t surpass all the other great songwriters on that record.

As the 60s progressed, Gerry became obsessed with Dylan, did too many drugs, and lost sight of his marriage. Carole moved to Laurel Canyon and, with the encouragement of James Taylor, reinvented herself as a recording artist on her 1971 album Tapestry. The commercial apogee of the introspective singer-songwriter movement, Tapestry‘s effect on the culture can hardly be overstated. Sitting by the window of with two cats, King gave the everyday woman of the 1970s the proverbial room of her own. To this day, “It’s Too Late” vibrates with the sound of a thousand marriages disintegrating under the weight of unwanted expectations.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E5TxpJVKKQ8

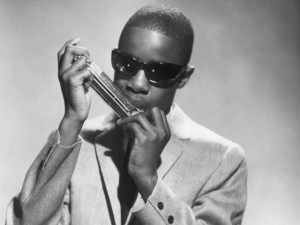

4. Stevie Wonder

The comparison of Berry Gordy’s Motown Records to the Ford Motor Company works on at least three levels: located in Detroit, organized like an assembly line, and founed by an autocratic chieftain. Marvin Gaye’s refusal of the vision Berry Gordy had in mind for him happened earlier, but Stevie Wonder’s break was even more unexpected. Little Stevie Wonder, the 12-year-old genius of 1963?

But by the time he turned 21, Stevie Wonder could no longer contain his musical creativity, and he used his expired contract to wrest creative control from a very reluctant Gordy. The result of was a streak of eight albums through the 1970s that brought new levels of harmonic and rhythmic complexity to soul and funk music, with an emotional exuberance that still takes away the breath of listeners today.

3. Pink Floyd

Has any band ever recovered from the departure of their charismatic founder and frontman more successfully than Pink Floyd? Syd Barrett may not deserve sole credit for tapping a whimsical/creepy British vein of psychedelic fantasy, but he did it better with more singular, brilliant vision than anyone else before deteriorating into an acid casualy.

Now, there are Barrett partisans, and then there’s the rest of the world who have evidently purchased Dark Side of the Moon and Wish You Were Here at least three separate times. I’m highly partial to the many Roger Waters/David Gilmour periods that followed — the spotty but charming space-rock that carried them through the 60s, the ear candy of Echoes and Dark Side, the pretentious Roger Waters albums. But their debut album The Piper at the Gates of Dawn ranks as highly as any other iconic records of 1967 — your Sgt. Pepper’s, Are You Experienced, the debut Doors album, you name it — thanks largely to Barrett. Shine on, you crazy diamond, indeed.

2. Fleetwood Mac

Probably the most significant lineup change in terms of commercial impact, the case of Fleetwood Mac is paradigmatic of the musical reinvention. For some seven years, Fleetwood Mac slugged it out first as a British blues project and then a mumbly folk-rock group enlivened by the arrival of keyboardist Christine McVie (née Perfect — look for her pre-Mac recordings with the group Chicken Shack). They had enough success to tour overseas and get an American record deal, but continuing lineup instability provoked Mick Fleetwood and the two McVies to make a game-changing move. The addition of California-based singer-songwriters Stevie Nicks and Lindsay Buckingham (the latter an extraordinary guitarist and producer) turned Fleetwood Mac into the emotionally turbulent and massively successful soft-rock band that everyone knows.

The change in style paralleled a change in location. Fleetwood Mac was associated with the London blues scene where founding member Peter Green was a guitar hero. Eight years later, they had become a quintessential Southern California band. Having grown up in coastal California in the shadow of Rumours, it’s hard for me to be objective about the Mac. In my mind they’ll forever be the soundtrack to the 70s era of grown-ups sowing their oats, freed from the conventions of romantic fidelity. I wouldn’t recommend that lifestyle for most people, but I still love Fleetwood Mac for miles.

1. Bob Dylan

Okay, I said this category doesn’t include musicians who change their persona so frequently that it eventually becomes their trademark, a designation that certainly applies to Bob Dylan. But his most important reinvention, so well known that it’s an everyday phrase — Dylan goes electric — created shockwaves that still reverberate through popular culture. For one thing, it established folk-rock. For another, it troubled the old left’s bugaboo of artistic ‘authenticity,’ a specter that still haunts popular music, a thousand critics’ embrace of Miley Cyrus notwithstanding. And of course, bgoing electric, Dylan almost single-handedly brought an end to that specifically middle-class (and white) fascination with folk-music tradition, which was of course the stock and trade of Greenwich Village, New York.

As a historical event, Dylan’s going electric essentially created this cultural motif of the artistic reinvention — his sly denials notwithstanding. For establishing this category, at least within the context of contemporary popular music, I’m giving the guy his due.