Part two of my response to the question, which performers made the most unexpected left turns with their careers? For the ground rules of eligibility, click here; for the big picture of what this all means, click here.

PREVIOUS:

50-41

40. Grace Jones

A Jamaican-born model, Jones seemed born with a knack for commanding people’s attention, which she used to hold court at discotheques in the world’s fashion capitals. Her recording career began in 1975 with a frothy disco single, “I Need A Man”, recorded for a French label (unsurprising, considering her impact on the French modelling world) and produced by disco remix pioneer Tom Moulton. Chris Blackwell’s Island Records signed her and issued three full-length disco albums released over the remaining decade. Appealing and interesting enough, particularly for the choice of Broadway tunes and French ballads that she covered, they nonetheless teeter on the precipice of anonymity — an unsustainable proposition for Grace.

It was the next trio of albums, ostensibly comprising her new wave period, that made Jones’ musical legend. Recorded at Blackwell’s retreat in the Bahamas, they occasioned the formation of one of the greatest studio bands, the Compass Point All-Stars. “I wanted a new progressive, sounding band,” Blackwell said, “a Jamaican rhythm section with an edgy mid range and a brilliant synth player.” What he got was Sly Dunbar, Robbie Shakespeare, Barry Reynolds, Wally Badarou, Mikey Chung and Sticky Thompson, whose arrangements and performance alongside Jones on Warm Leatherette (1980), Nightclubbing (1981) and Living My Life (1982) transcend the new wave label to create something entirely unexpected, and still ageless.

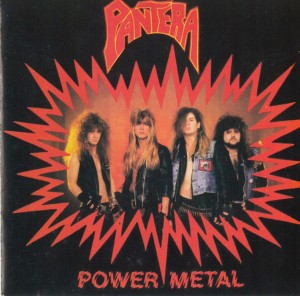

39. Pantera

Their 90s-era “power groove” was never the kind of heavy metal I favored, but you gotta recognize this Texas metal unit for their distinctive sound and audible influence over later generations of downtuned doom and sludge metal. This is all the more remarkable considering how they began as a Dallas-based glam metal band, whose first two albums the surviving members would just as soon erase from public memory. Even the 1988 arrival of new vocalist Phil Anselmo, today one of extreme metal’s revered keepers of the flame, didn’t make a complete break with the glam sounds that were increasingly reviled by metal’s hardcore fans.

It’s really testimony, then, to the impact of the band’s 90s albums, marked by Dimebag Darrell’s chromatic riffing and Anselmo’s bad attitude, that Pantera has entered into heavy metal’s canon. Considering how that decade saw established groups dip ill-advised toes into “industrial music” while a cohort of “nu metal” losers emerged — Satanists from Scandinavia were too obscure to reach many North American metal fans at this time — their achievement is all the more significant.

38. Julian Cope

It’s customary to commence any discussion of Julian Cope with a reference to the Teardrop Explodes, his short-lived neo-psychedelia group from Liverpool that may or may not have been cooler and more clever than local rivals Echo and the Bunnymen. I’m not sure why this is customary, because the Teardrops were up and out in 5 years’ time, while Cope’s career has continued for over three more decades. Still, he would randomly draw upon the Teardrops’ qualities — a little dope-addled mania here, some dated studio sheen there — over the course of his 1980s albums, eventually with diminishing returns. No amount of drug taking or encyclopedic musical knowledge, it seemed, could prevent Cope from falling into serious creative and personal burnout by the decade’s end.

So how did Cope become the righteous “archdrude” he is today? As his 1991 comeback album Peggy Suicide documents, joining in the fiery protests over Thatcher’s poll tax plugged him into the new political communalism bubbling under rave-era UK. His rekindled mystical visions have since sustained a writing career that has yielded lauded works in musical history (his 1996 book Krautrocksampler had a major impact on underground music of the time) and neolithic archaeology. His howling, hilarious manifestoes of rock mythology are featured on his Headheritage website and, most recently, his first novel; wife Dorian’s blog On This Deity suggests her considerable influence on Cope’s thinking and productivity. And while his music since the 1990s has shown more purpose and substance than almost any of his better-known earlier work, that’s almost besides the point. For a committed paganist, Cope essentially operates today as a renaissance man.

37. Scott Walker

Scott Walker of the mellifluous baritone (not the Wisconsin governor’s house, just to make that clear) was always deep. In 1967 he left the Walker Brothers, an American quartet who had some chart success in England, to record four remarkable albums of mature compositions, sophisticated arrangements, and masterful vocal delivery. There was obviously an intelligent, troubled soul at work in the icy, impeccable songs of his first four albums (the essential Scott 1-4, recorded between 1967-69), but listeners could easily tune it out, so seductive was his easy listening music. The dissonance Walker conveyed was generally confined to lyrics or, as in the string arrangement on “It’s Raining Today,” limited to a teasing aural suggestion.

After Walker’s art got away from him in the 1970s, which he spent recording vapid easy listening (that he has subsequently refused to re-issue), he seized control again in a willful act of artistic exile. His subsequent albums each came out 5-10 years apart, accompanied by no publicity or (after 1984’s Climate of Hunter) images of Walker. These records descend deeper into disturbing, sometimes terrifying musical abstraction, Walker deforming his famous croon to narrate laments of despair and meaningless. Famously, the sound of “meat punching” can be heard on “Clara” (on the 2006 album Tilt), an ode to the woman who hanged herself with Benito Mussolini. These are pointedly uneasy listening albums, virtually impenatrable yet crafted with a care that evades most prolific noise artists. The documentary film “Scott Walker: 30 Century Man” cast a sliver more light on to this mysterious artist; his 2001 production on Pulp’s final album suggests a little humor leavens his self-awareness of his legacy. Still, the persistent obscurity over his artistic motives or current biograph only deepens listeners’ fascination with this cult musician.

36. Ultravox

Japan, the British pop group fronted by David Sylvian, could perhaps occupy this space just as easily. But arguably Ultravox, so unfairly mocked by the British press, had a bigger hand in the sounds and styles of the early 1980s. As Ultravox! (please note the exclamation point!), they started out in 1974 with a non-uncommon love for Bowie circa Diamond Dogs, Roxy Music, and Kraftwerk. Frontman John Foxx looked good but had a wooden vocal style, and the group disbanded after three well-meaning records that failed to make much commercial impact.

Keyboardist/violinist Billy Currie then found work subbing in for the final Tubeway Army line-up (that’s him in the Gary Numan video found in my last post) and collaborating with London club entrepreneur/fashion victim Steve Strange on the first recordings by Visage, the seminal new romantic group. The dramatic, classical piano flourishes he added to Visage’s sound (particularly on “The Steps”) proved inspiring; so, too, did working with Midge Ure, a Scottish guitarist and glam-rock prole who had just left a gig touring with Thin Lizzy. A call was made to the old rhythm section, and Ultravox Mark II was born — maybe more pompous and swarthier looking than the first version, but wildly successful at creating driving, emotional rock music with which to pose in pegged pants.

35. Tori Amos

I know, I know: I said solo turns don’t qualify for inclusion on this list, but I’m going to bend the rules for Tori Amos. Y Kant Tori Read was the album that first introduced the singer-songwriter to the music world. The elements of her future success are all there: her piano, her songwriting credits, and most importantly her record contract. Y Kant Tori Read (buzz off, spellcheck!) was a real band — an inocuous, indistinctive pop-metal band from Los Angeles — but evidently the record label urged Amos to sack the original members before recording their eponymous debut. Guest musicians like Cheap Trick’s Rick Nielsen and Robin Zander, a pre-G’n’R Matt Sorum, and the guitarist from Mr. Mister filled in, competently but with no real sense of purpose. The album fell flat artistically and commercially, and Amos spent four years strategizing her comeback before calling in her chips with Atlantic Records to release her proper debut, 1992’s Little Earthquakes.

34. Marvin Gaye

Marvin Gaye’s story seems to follow a familiar arc: an artist begins a career recording an accessible yet conservative style of music, fails to reach a broad audience, then gambles on a personal style that (surprise, surprise) really connects commercially and artistically. That’s almost right, except that Gaye’s story involves two left turns. His career in R&B began at a young age in the Washington D.C. area; when he signed to Detroit’s Motown Records, he initially recorded in the jazz vocals/easy listening mode of Nat “King” Cole — a style Gaye had embraced but which was already out of favor with the young listeners sought by that label president Berry Gordy. Gordy overruled Gaye’s wishes and made him an R&B singer, solo and in duet with Tammi Terrell and other Motown vocalists, to great success.

Some seven years later, Gaye’s vision was realized — this time because it had eclipsed the style promoted by Gordy. Terrell’s tragic death, his brother’s return from Vietnam, and his observations of injustice in an increasingly angry and volatile society provoked Gaye to raise consciousness with a new, more mature music. Gordy refused, worrying that it would be too political for Motown audiences, but his attentions were distracted by the label’s move to Los Angeles. Gaye called Gordy’s bluff and released the “What’s Going On” single, which topped the charts in 1971. Emboldened, he finished the rest of the What’s Going On album, a milestone in the evolution of soul music; its success gave Gaye the license to create the more mature (if less political) music that defined his late-career persona.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S67ETkOzAck

33. AC/DC

Some of us will always think of these Australian rockers as Bon Scott’s band. The little dude with the missing front tooth, bell-bottom denims and a proudly exposed midriff didn’t just look like he could wipe the floor with any barroom thug. Scott projected a menace as powerful as AC/DC sounded — no wonder fans thought the band’s name stood for Anti-Christ/Devil’s Children. And yet he was unafraid to hit the stage in drag or strapping on a set of bagpipes! Truly this was one of the great, iconic frontmen of hard rock, equal in stature to Ozzy Ozzbourne or Rob Halford.

Needless to say, Bon Scott never lived to enjoy AC/DC’s greatest success. At the age of 33 he choked on his own vomit while the band was writing material for Back in Black, which they eventually recorded with Brian Johnson, an equally muscular yet more affable screamer from the British group Geordie. Back in Black went on to become (by some estimates) the second biggest selling album of all time for good reason: it’s a perfect record, with a crisp, unadulterated sound and a flawless track list. But with Back in Black, AC/DC left the Satanic panic behind, “Hells Bells” notwithstanding, and become the slightly safer if still unrelenting hard rock institution that most of the world now recognizes. Fortunately, Bon Scott had his final gasp with the 1981 release of Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap, an album that in fact was five years old but gave Scott his proper eulogy with its title track.

32. Bill Haley and the Comets

Music historians love to debate who recorded the first rock’n’roll music. “Shake, Rattle & Roll” reached #1 in 1954, but in its original version by Big Joe Turner, and only on Billboard’s R&B chart; because of this last technicality, or because Turner wasn’t white, this event is often discounted when the question turns to who first topped the charts with a rock’n’roll recording. For right or wrong, that distinction is usually accorded to “Rock Around the Clock” by Bill Haley & His Comets. Certainly Haley’s single made rock’n’roll a global phenomenon when it played under the opening credits of the 1955 teen exploitation film “Blackboard Jungle”; thereafter it reached the top of the U.S. and U.K. charts in 1955, sometimes returning to various charts years later.

Although he doesn’t often figure in rock’n’roll’s first pantheon, Haley deserves credit for sniffing out the commercial potential of this new music at a time when it hadn’t yet crossed over. Tellingly, Bill Haley and the Comets began as Bill Haley’s Saddlemen, a country swing band that profited from his musical discoveries as music director of WPWA in Chester, Pennsylvania. Haley’s fusion of R&B and country into rockabilly was one of the purest, evidenced as early as his 1951 recording of “Rocket 88.” The whack of the snare heard on “Rock Around the Clock” must have sounded like gunshots to the parents of children under the song’s spell.

31. Talking Heads

The achievement is often forgotten now, but Talking Heads did as much as any other group in rock or pop to deconstruct the notion of ‘the band’. The process began with their second album, 1978’s More Songs About Buildings and Food, which was produced by Brian Eno during his NYC years. His relationship with the quartet over their next two albums and 1981’s Eno/Byrne record My Life in the Bush of Ghosts went beyond the traditional relationship of producer to band. Sure, other producers play and (on Remain in Light) cowrite on their artist’s records as well, but Talking Heads weren’t like other artists — they never lacked in overall vision and purpose. Instead, Eno’s contributions suggest he was brought in as essentially a fifth member to oversee the careful, collective redirection of the band’s creativities.

If the rest of the band was ultimately not as comfortable with Eno’s influence as frontman David Byrne, they were nevertheless in tune with the radical expansion of the band’s ranks for the recording and touring of Remain in Light. Even after Eno stopped working with the band, the band retained an extended unit through Speaking in Tongues and its tour, which was captured in the Stop Making Sense concert film. (The Tom Tom Club, Talking Heads’ most famous offshoot, took this approach as well.) It’s hard to understate how unconventional this approach was in the rock-centric late 70s and early 80s, particularly for white audiences witnessing a battery of African American musicians alongside the band on stage. It’s also remarkable how many musical luminaries had a semi-permanent role in Talking Heads, including guitarist Adrian Belew, keyboardist Bernie Worrell, and singer Nona Hendryx. This experiment may even worked too well, because it seemed the spark had left Talking Heads when the ‘original band’ returned for 1985’s Little Creatures.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6g8lFmsCXhg

NEXT:

30-21