Restless Records, 1989: from an independent label intern’s view

by Leonard Nevarez on Dec 14, 2013 • 12:18 am 6 CommentsThe inspiration for my latest post: a request.

How cool to find out @enigmarecords, where I did my first internship, is on @twitter. Tweet more, Enigma! What are the Effigies up to?

— Mara Schwartz (@mara_schwartz) December 8, 2013

@MusicalUrbanism @EnigmaRecords I would like to read this.

— Mara Schwartz (@mara_schwartz) December 9, 2013

In my senior year at UCLA, I interned at the independent record label Restless Records in Culver City every Friday. For the first half of the year, I’d come back home and type up 3-4 single-space pages of fieldnotes documenting the day’s experience and observations. These formed the data for this paper, the final requirement in my Qualitative Field Research course taught by Juniper Wiley. She gave this an A-, commenting that I could have engaged the scholarly literature better, and that I should have relieved the tedium of a 10-12 page paper by inserting some section breaks. (Funny, I often make this last comment on my students’ papers.) I then entered this paper into the UCLA Sociology Department’s undergraduate conference, where it won first place in the micro-sociology category.

Originally I assigned pseudonyms for the record labels I studied: Restless Records was “Upstart Records,” Enigma was “Zenith,” Medusa “Gnarly” and so on. Below I’ve reverted to their real names because the label is now defunct (although Enigma survives in some form today), and because the analysis is fairly uncontroversial (I gave a copy to a few employees including my immediate supervisor, none of whom had reported any objections or embarrassment). However, I kept the pseudonyms for the people described here, although a little online research will turn up the top folks’ names; honestly, I can’t remember anyone’s names anyway. If you’re referenced below and are out there reading this, drop me a line!

The writing here is artless, the conceptualization bland, and a tone of ‘objectivity’ is used with no irony whatsoever (long-haired 21-year-old me was genuinely surprised that the label’s bosses and employees might be long-haired rockers themselves). But some 25 years later, what I find most interesting about this paper is how, long before I had any interest in graduate school much less a career in sociology, it presaged recurring themes in my subsequent scholarship on the ‘new economy’:

- how employers value workers for their personal flexibility and involvement in high-status urban communities (in this case, the Los Angeles music scene);

- how workers trade income and security for goods, services, status, and future opportunities (CDs, concert tickets, living the rock and roll life, and promoting their band); and

- how externalized labor markets eclipse the bureaucratic firm as the context for labor reproduction and the organization of a career.

So return with me now to a time before e-mail and the internet, when LPs were list price $8.98 and CDs $15.98, back when Los Angeles was still an aerospace sector center and not the capital of the culture industries…

The Culver City building where Enigma and Restless Records were located back in 1989, as seen today from a Google Street View image. All the photos and captions in this post are contemporary.

This essay concerns the study of a workplace culture which I observed at a small, independent record company. I was granted this opportunity to observe this culture through my internship at Restless Records, one company in the growing “alternative music” industry. My work at this record label, in the department of National Radio Promotion, provided the framework for a participant observation research setting. The data of my research was culled from the field notes recording the observations I made during my internship every Monday for a span of five weeks. All data was generated by three methods I found appropriate for my intern role: 1) general observation and description of setting and events; 2) transcription of dialogue among employees; and 3) analysis of my internship tasks and those of other employees.

Before I begin my discussion of the workplace culture of Restless Records, I think it is necessary to detail in brief its background as an independent record company. Restless Records was created ten years ago by two young Los Angeles entrepreneurs, Mark and Todd Cohn. It grew out of Enigma Records, a record company they formed to serve an alternative music market. As Enigma’s market grew, the Cohn brothers created Restless Records to service the alternative music market that Enigma once did. In addition, they also formed other labels, such as Restless’s office mate Medusa Records, which capitalizes on the growing heavy metal/hard rock market. The fate of Restless Records is tied to the success of its “mother” company Enigma; as the latter expands, so does the former.

Restless Records is one of many flourishing small record labels, independent of any major record companies or entertainment corporations, servicing the alternative music market. Its music caters to a particular segment of the popular music audience, namely those listeners of underground, grass roots, or “alternative” music. Restless reaches this audience through sale of its records at alternative music record stores; also the company promotes its music in the alternative music press and through airplay on most college and some commercial radio stations (this last area being the primary concern of the department under which I interned, National Radio Promotion). Through these channels Restless Records distributes and promotes its product: records, cassettes, and compact discs by underground and experimental artists. Their releases are not meant primarily to reap commercial gains — a successful Restless album sells 10-20,000 copies, whereas in the mainstream pop market, a successful album sells in the hundred thousands — although it should be noted that the Cohn brothers are known in the music industry to have a keen business sense in capitalizing upon the expanding alternative music market. Nevertheless, now that Enigma Records is their forum for commercial aspirations, they have endowed Restless with an alternative aesthetic, seeking out innovative, unique, and underexposed artists, as decided by Restless Records label manager David Ryan.

The record that established the label’s alternative credentials: the 1985 “Engima Variations” compilation. In the mid-80s, this double album was ubiquitous in a certain kind of American record store.

My focus here is on the workplace of Restless Records, whose staff of 12-15 make the decisions and carry out the functions of the company. In this setting I will describe the culture that has emerged from their activities. By “culture” I refer here to David Becker’s [sic! Howard Becker’s -ed.] definition of the term as those shared understandings among a collective which help its members to coordinate their actions together (Becker, 1986). Of course, any workplace will have its own culture if workers are to work together efficiently; such shared understandings would encompass the purposes, processes and functions of their work duties, both individual and collective, to name but a few examples. However, as I will reveal, the workplace culture at Restless Records is remarkable in that it is consciously created and sustained by both its employers and employees for reasons not originating from the business of the company.

I should begin my description of the “Restless culture” with its location and spatial arrangement. Restless Records can be found sharing the bottom floor with Medusa Records in one of the two 2-story buildings (about 100×50 yards) owned by Enigma. The parent label keeps the top floor for its executives, while the next door building is where most of Enigma’s 40-60 employees work. The one floor designated to Restless and Medusa is arranged in a rectangular shape; one hemisphere is a warehouse and mailroom in which thousands of records are stored and shipped. The other hemisphere of the floor houses the offices of Restless and Medusa: the Restless retail office, a small hallway doubling as the “intern room” (which contains a table and two phones), and a small foyer connecting three offices belonging to Medusa label manager Will Meyers, David Ryan, and the Restless Radio and Press representatives. Off to the side is an all-purpose office supply, xerox, fax, and soda machine room.

This is the physical setting in which the employees of Restless and Medusa Records work. The Restless label manager oversees three departments: Retail, Press, and Radio (my department). The Medusa label manager has only one radio representative, while the retail and press duties are handled by Restless staff. The departments are managed by one employee each, except for the Restless retail department, whose representative has a part-time assistant. It is interesting to observe that five Restless/Medusa “reps” were all women; in contrast the duties of the mailroom were handled by men, as were the label manager positions. The two label managers were white men in their 30s; the women white (except for one Asian) in their 20s; and the men in the warehouse were also in their 20s, all white except for one Latino. I should also mention that all the other “support” functions needed by Restless and Medusa are serviced by Enigma staff, as is much of the administrative decision-making, and so are included in references to the “Restless culture.”

While it is difficult for any participant observer to convey all the details of the setting he or she is documenting, I will describe those qualities of the Restless culture which I found shed light upon the meanings of the participants of my setting. First and foremost, I perceived that the Restless culture was characterized by a colorful and informal atmosphere. From my first day in the field, I was continually impressed by how the employers and employees appeared, interacted, and carried on, shattering many of preconceptions of how a “formal” business operated.

11/6/89 (at intern orientation) — Behind the table is a large, portly man in his 30s with hair down to his back and a long beard, wearing a red flannel plaid shirt, jeans, and tennis shoes with yellow laces… “I’m the Vice-President of Creative Services, which means that I’m in charge of servicing all the creative functions at Enigma, Restless, and all the other labels: art, publishing, etc.”

10/30/89 (Saul of the mailroom) — … A white male in his 20s, with his hair in dreadlocks of shoulder length; he is in red sweatshirt, jeans and tennis shoes.

At Restless there seemed to be no concern for “proper attire.” I had difficulty distinguishing executives from reps, clerks and custodians until I came to identify faces with names and positions. The company seemed to recognize only a norm of pragmatism: If you can work in those clothes, then they are acceptable. This provided a wide range of self-expression through personal appearance, from “casual” clothes to jewelry to long hair.

Also contributing to this informal atmosphere were the vivid decoration and ornamentation of the offices. Posters of Restless artists were posted on the walls, with little regard to neatness or angularity. Many employees had their desks and bulletin boards boards cluttered with photos, badges, ads, and other promotional items of Restless artists as well as their personal favorite musicians. Many displayed personal motifs or “inside jokes” For example, my boss Sandy had her walls covered with decorations Pee Wee Herman, a popular comedian; in the same office, press rep Claire ironically placed pictures of pop star Bon Jovi all over her desk, as well as life-size promotional stand of his likeness in front of her filing cabinet. A third contributing factor in this informal atmosphere is that the staff was always listening to music. This is perhaps not so surprising, since this was company’s business; for example, much of the label managers’ jobs was to listen and make copies of new music cassettes so as to decide whether their label should release it. However, many employees also played their own cassettes by artists with no relation to the company, seemingly just for their own listening pleasure.

A second quality of the workplace culture at Restless was the company’s relaxed emphasis on efficiency. Very early on I observed how Restless did not “run a tight ship” at the workplace, yet employees seemed to perform all the duties necessary for the functioning of the company. Most workers arrived at the office usually around 9:30 a.m. Once again I sensed a norm of pragmatism at work: It did not matter when you arrived, so long as you had enough time to complete the day’s tasks. For example, Sandy told me not to arrive earlier than she did at 9:30; yet often, when I had to leave at 4:00 p.m., she would inquire whether I could stay on longer to help her if an irregular project (such as mailing out record to radio station) had not been finished.

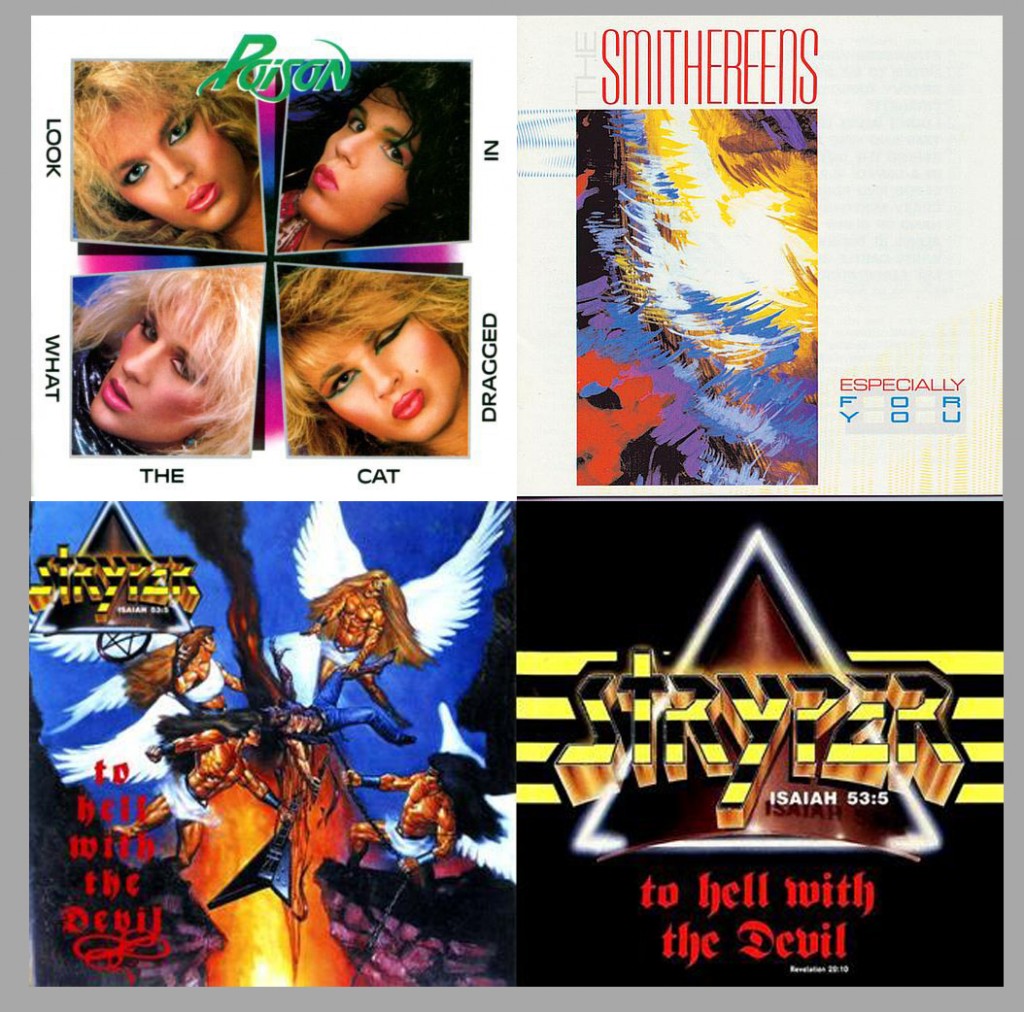

Enigma Records had massive success with these three albums (two different covers for the Stryper record), leading the parent label to focus on music with more commercial prospects and to relegate its alternative music to Restless.

Another aspect of Restless’s relaxed emphasis on efficiency can be found in their telephone habits. Most of Restless’s business is conducted across the nation via long-distance telephone. The company therefore places great effort to maintain harmonious client relationships through light yet persuasive conversations. Most business calls made by employee usually lasted from 5-15 minutes, beginning with light conversation (e.g. personal gossip, opinions on recent music); later the Restless caller would steer the conversation “back to business” yet never hesitate to inject more light conversation into the dialogue.

11/13/89 (Medusa rep Tracey on the phone) — I realize that her conversation had turned to me as the subject. On the phone is my friend Kevin, one of her radio people, and she lets me talk to him briefly. Kevin is calling her because there is some new promotional items he wants from her; she in return is asking him if he is playing the new Medusa releases on his heavy metal radio show. Between these requests is talk about whom she is dating (“God, you’re nosy!” she laughs), the guitar amplifier I let him borrow and recently took back (“Kevin says he’ll give you your tape back when you give him back your amp,” she shouts to me from her desk), and other subjects.

In addition to these long business calls, I found Restless employees making personal calls a number of times from the company phones in the intern room I worked in.

10/23/89 — I return to the intern room where Jason the front door receptionist (in T-shirt and jeans, wearing a nose ring) is using the phone. He is making calls trying find “connections” for the band he is in and having some success in it. At one point he says, “Let me just find a pen…” so I hand him mine, to which he responds, “Thanks, bro.”

A third aspect of Restless’s relaxed emphasis on efficiency was revealed in the high incidence of personal conversations the workers struck up with each other spontaneously in their work. No time or place seemed inappropriate to chat, as employees conversed across their desks, at lunch, or walking to another’s office. Nor were subjects of discussion limited to business.

10/23/89 — While on the phone calling radio stations, I overhear China from the retail department stop outside Will Meyer’s (Medusa label manager) office door, telling him how much she likes the band he’s playing on his stereo; they’re her “favorite L.A. band,” she says. I ask her which band she’s talking about, and we start up a conversation about this group the Hangmen.

10/30/89 (leaving for lunch with Tracey) — “Wow, have you slept in this thing?” she asks, gesturing toward the cab of my truck (lined with carpet and covered by a camper top). “Well, no,” I reply, “although everyone jokes, ‘Wow, Len you’ve gotta bring a chick back here!’” She giggles, “So, you’ve never slept in the back of a truck with anyone before?” “Uh, well, no,” I reply as we start for the El Pollo Loco a mile away, “but I just got this a couple of months ago.” She smiles, “Wow, I don’t believe I’m asking you this. It’s just that I talk to my radio people about anything…”

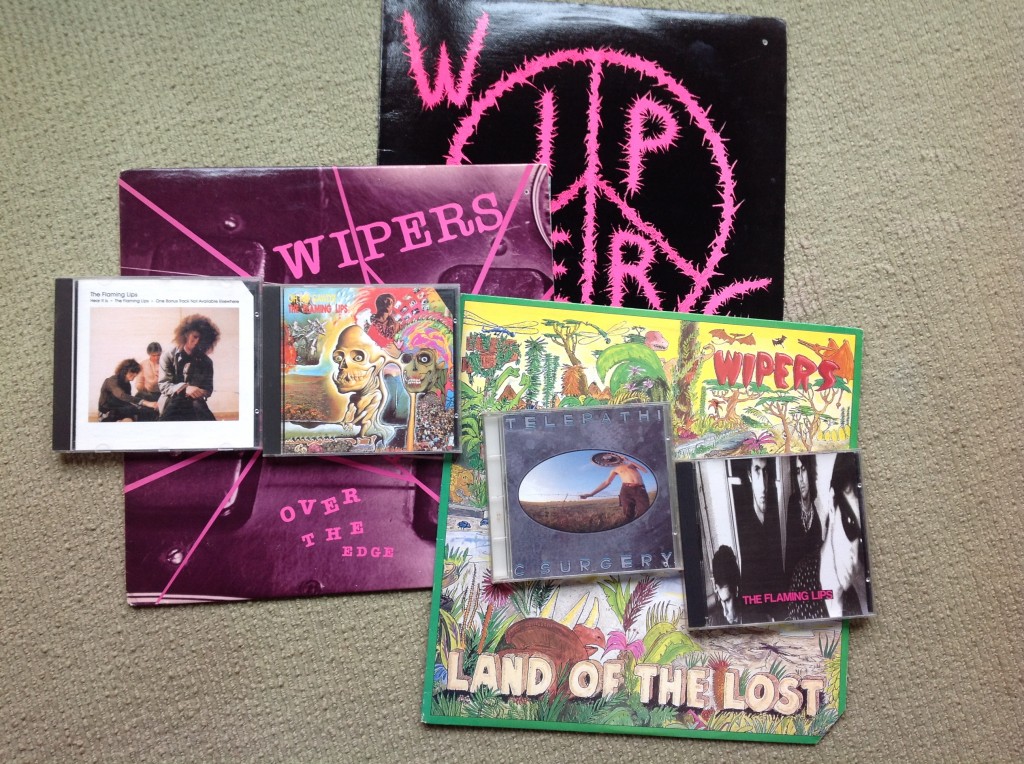

The Wipers and the Flaming Lips were in my opinion the most distinguished “Restless bands,” i.e., signed to and A&Red by Restless Records. (Some might include the Dead Milkmen in this category, but not me.) The Wipers fell into deeper obscurity after their stint on Restless; the Flaming Lips eventually blew up for Warner Brothers.

In addition to the informal atmosphere and relaxed emphasis on efficiency, a third quality of the Restless workplace culture is what I call a fluid recognition of hierarchical status. I noticed a very relaxed interaction among the staff; no employee acted with too much reverence toward a superior, nor did any employer seek to project an overly authoritative attitude towards an employee, at least in matters not pertaining to serious decision-making.

11/13/89 — As I return to the intern room, Vernon the janitor (the only black Restless employee, in his late 20’s) is seated at the table using the phone. I set down to resume work as Claire (Restless press rep) and Will both enter, she to get something from the promo boxes on the floor and he to dub another cassette. Will asks Claire if she did anything this weekend, and she says no because her sister was in town: “I tried to go see George Clinton, but it was sold out.” Will asks, “Yeah, where was that show?” As she tries to remember, Vernon interjects calmly: “The Strand.” She says, “Yeah, that’s right, the Strand in Malibu.”

While I would not suggest that Restless employees felt free to impinge upon the authority of their superiors, I would hypothesize that boundaries of interaction in the Restless hierarchy were mostly limited to work responsibilities. I could not detect any noticeable difference in the ways employees carried themselves in front of peers of superiors. Moreover, the staff at both Restless and Enigma seemed conscious of this fluid recognition of hierarchical status; Greg McCarty once mentioned to me that the Cohn brothers were “the type that you could walk up to their office, knock on their door and ask them anything.”

The three qualities of the workplace culture at Restless Records described here — the informal atmosphere, the relaxed emphasis on efficiency, and a fluid recognition of hierarchical status — are just a few of the shared understandings which I encountered in my setting. No doubt more pragmatic shared understandings exist at Restless, relating to the coordinated activities necessary for the actual functioning of the business (i.e. how people know how to do their jobs). I have chosen these three characteristics because they reveal insights into the meanings that employees and employers derive from their workplace. I now turn to an analysis of the workplace culture at Restless Records.

Becker has stated that all workplaces invariably generate some set of shared understandings — in essence, a “culture” — if employers and employees are to coordinate their activities to make any sort if work possible (1986). He seems to suggest, however, that this culture will spontaneously emerge from the workplace, perhaps as a product of the institutionalization of work procedures as routines. My research at Restless Records does not disprove Becker’s hypothesis, but it has generated data which suggests there may be another reason for the emergence of a workplace culture: the deliberate machinations of both employers and employees to shape the workplace to their own aims. These aims exist outside of the functions and processes of the company. In fact the aims of employers and employees have effectively created a negotiated order, at once articulated and unarticulated, but very real nevertheless.

I will first examine the employers’ aims which shape the Restless workplace culture. From their origins as a small organization operating out of their home, the Cohn brothers have articulated their desire to shape Enigma and its labels as an alternative to a formal bureaucracy.

11/6/89 (intern orientation) — Greg then discusses how every division at Enigma and its labels supports each other “with the minimum of paperwork and the maximum of accountability. While a major record company may have a separate division [of accounting, art, publishing, etc.] for each individual label, here we have one department doing it for everyone.” He talked about the success with which this approach had in reducing the bureaucracy and “keeping the human element” at Enigma.

This “human element” indicates how the employers have sought to promote positive, friendly interaction among all at Enigma and its labels; one can better understand their reasoning when one analyzes the dynamics of a very small organization. Another employer consideration is to foster employee satisfaction in order to promote their staying on at the job, something the employers deem vital if their organization is to grow.

Restless had a very productive relationship with the Hoboken, NJ label Bar/None Records, distributing and promoting the albums that Bar/None signed, A&Red and packaged.

Another employer consideration in allowing such an exceptional degree of informality is their desire to keep in touch with their target market. This motivation should be analyzed in light of Restless’s existence as an “alternative” or underground music company. Often during my internship, Restless recording artists would visit the office, and I realized how an observer unfamiliar with the workplace would have difficulty distinguishing the musicians from the staff, thanks to the high degree of self-expression in the workplace. As one employee mentioned to me, the executives at Enigma and its labels are aware of their need to keep an “ear to the street”; the informal atmosphere of the Restless workplace, particularly their “unprofessional” appearance, is seen by the employers as a means to minimize the gap between the musicians and their label. At the very least, this informal atmosphere is seen as an incentive for musicians to stay with the company instead of seeking another with possibly greater resources.

As I have started previously, the employees at Restless Records also play a conscious part in shaping their workplace culture to their own aims. Many employees find the unique qualities of the Restless culture as an important source of job satisfactions. The informal atmosphere, the relaxed emphasis on efficiency, and the fluid recognition of hierarchical status are all factors in why employes are attracted to work at Restless and why they stay on. As one employee stated, “How many other jobs do I get to dress like this, listen to music, and get paid for it?”

Another important consideration in Restless employee aims is that they feel that more formality in the workplace (e.g. more formal business wear) is not appropriate for their jobs. There is that reason I stated among employer aims, the need to keep in touch with their market, but here I am focusing primarily on their work and wages. A job at Restless, Enigma, or Medusa is not strictly white collar. The tasks of a label rep range from making business calls to compiling and mailing thousands of record packages to traveling nationwide on business to helping Restless artists. (One rep even let an Restless band stay at her apartment for a few days.) The relaxed emphasis on efficiency does not mean that tasks at the workplace do not get done; employees put in long hours often and are expected to “take their work home” if need be, even if this might only be attending a Restless concert, for example. Yet this type of work does not mean that mean employees are necessarily well paid. Many jobs at Enigma and its label pay part-time wages (e.g. $400 a month) [about $750 in 2013 dollars -ed.], while more suitable career positions demand intense work.

11/13/89 (lunch with Judy, a Enigma employee) — As we leave, I mention that I know she has a new position, but I forgot what her title is. “I’m an Alternative Radio Director at Enigma,” she says. When I ask her it it’s OK to ask how much she’s making, she tell me she earns 23 thousand a year [about $43,000 in current dollars -ed.]. “It’s really not that much. I work really hard — I haven’t had a full weekend at home in two weeks.”

Episodes like this made me realize that employees at Restless and the other Enigma labels feel a higher degree of formality in the workplace is not commensurate with their current workload and wages.

The analysis of employer and employee aims in shaping the Restless workplace culture suggests they have, in effect, entered into a negotiated order concerning their workplace culture. This order could be stated as such: The employers at Restless Records offer to their employees all these qualities of their workplace in return for the employees’ low pay and hard work to the company. My articulation of this negotiated order is admittedly crude, but hopefully it stresses the cost/benefit aspect of this relationship to both the employers and employees at Restless and the other Enigma labels. It is not my intention to guess at psychological reasons for why this negotiated order is satisfactory to both parties. Instead, I will examine a fourth quality of the Restless workplace culture which I call the norm of favor-reciprocity. An analysis of this quality more so than any other of the workplace culture, will serve to illuminate the negotiated order at Restless Records. The norm of favor-reciprocity refers to the practice of Restless employers and employees to bestow favors upon others either as a means of positive reinforcement or in the hope of gaining influence for future needs. The favors can be gifts, such as Restless compact discs or concert tickets, or they can be privileges, such as permitting an informal atmosphere or letting an employee take an extra day off. Finally, the norm of favor-reciprocity exists as both a function of business practices and reinforcement of the negotiated order; I will examine the former before returning to my analysis of the latter.

There are several business practices at Restless which demonstrate the norm of favor-reciprocity. As an intern, one of my tasks was to call music directors at college radio stations nationwide and “track” Restless releases, that is, to inquire and log if and how these releases were being played by that station. If a station was focusing heavily on a particular release, then it was up to my discretion to set up a “giveaway” of that release; this meant I would send five records to be given away as radio contest and/or five cassettes for the station’s staff, presumably so they could listen to the release at their own pleasure. I did this under the National Radio Promotion department, and that title clearly indicates what the purpose of the giveaway is. Such giveaways are seen as an effective promotional device; as my boss Sandy told me “When something’s doing good on the charts, we try to shovel out as much of it as possible” Of course, such gifts as extra cassettes might come as a pleasant surprise to a disk jockey in Bozeman, Montana, for example, and my experience at Restless suggested to me that this was an intended consequence. Giveaways at Restless are seen as favors which could possibly exert some influence on a station, so that a music director might now look more favorably upon future Restless releases than had he or she received the giveaway (i.e. return the favor).

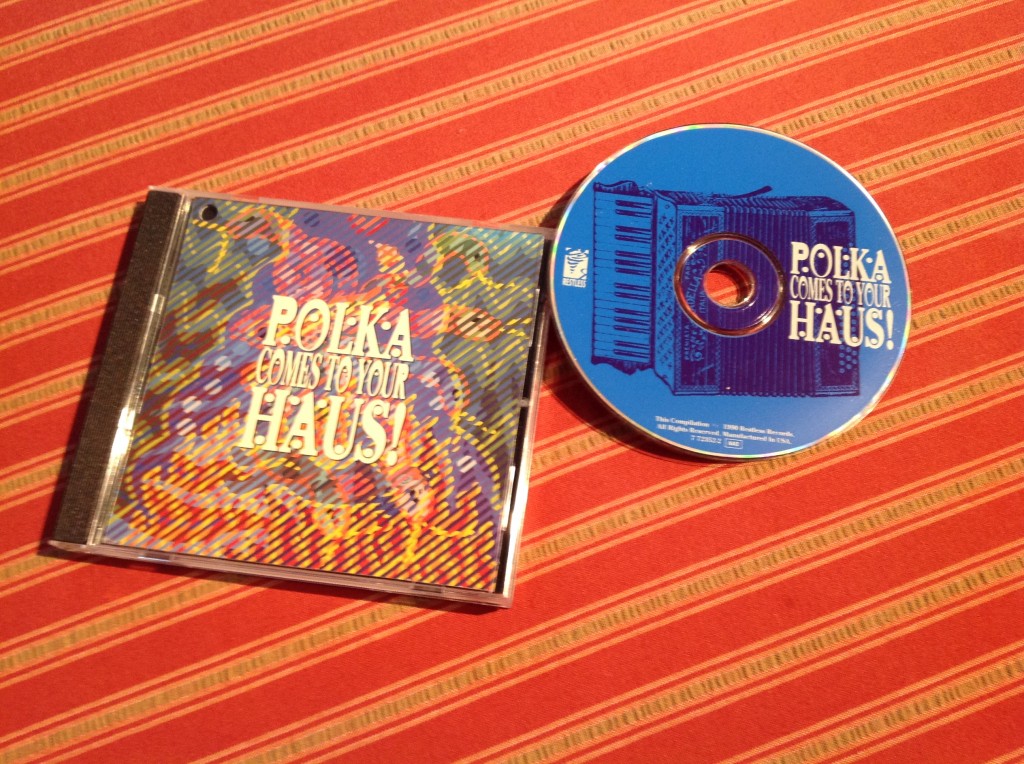

One of the many records I tried to slog in the National Radio Promotion office. Restless had a penchant for jokey alternative and punk music: Elvis Hitler, the Pajama Slave Dancers, this compilation of alt-polka music (the title evoking the famous punk compilation “Hell Comes To Your House”)…

Another business practice at Restless involves buying a small number of tickets at each Restless concert in case they should need to be given out as a business favor. The rationale here is that anyone involved in setting up or promoting an Restless concert, such as a promoter or interviewer should not be made to pay for their own ticket. It is up to the discretion of the Restless rep working on the concert to decide upon who, among all the eventual requests, is important enough to get in on this guest list. An amusing and revealing fact is that the column under which employees log the names for a concert guest list is titled the “pest list.” Clearly, this was intended as humor, but it does highlight an important aspect of the norm of favor-reciprocity: Restless Records must pay the cost of the initial favor if they are to gain any influence upon their clients.

The norm of favor-reciprocity also reinforces the negotiated order between the employers and employees at Restless and the other Enigma labels. In most cases, the bestowing of favors is an unarticulated reward for the work the employees perform at their job.

11/13/89 (lunch with Judy) — Also, she said she thought her boss felt guilty for keeping her underpaid “because he does stuff like let me take the day off when I’m supposed to be at work,” among other things.

As this episode suggests, the negotiated order is not necessarily perceived by the employees as deceptive or exploitative on the part of their employers. Instead, employees seem to accept the terms of the negotiated order, seeing the costs as outweighed by the benefits of the Restless workplace culture, Instead of seeking to change the negotiated order, the employees shape the Restless culture (with the tacit approval of the employers) to help ease the costs of their workload and low wages. The norm of favor-reciprocity is perhaps the most obvious manifestation of how employees consciously shape the workplace culture for reasons other than business.

One example of how the norm of favor-reciprocity works to the employees’ benefit illustrated in all the free records, cassettes, and compact discs they receive. The employees allow the label reps to dole out extra promotional copies of the latest Restless releases to all the other staff. As I observed how music was the primary passion of almost everyone who worked for the company, I realized that this reward of free music was not trivial. Indeed, as an intern, my sole income from the labors I donated to Restless would come as the free promotional records and other items I could pick up at work. I calculated that one day I brought home at a retail value of about $60 [$113 in current dollars -ed.], all for free and with my boss’s approval: “If you want anything, go ahead, as long as it’s in reason.”

If I’m being honest, it was Restless’s reissues and distribution deals that had the biggest influence on my music collection.

Thus, employees at Restless view any free records, concert tickets or other promotional items as supplementary income which offsets the costs of the negotiated order. They increase this supplementary income by networking outside the record company with other reps at other record companies, gaining access to more free items.

11/13/89 (lunch with Judy) — she admitted that “I don’t have to pay for any records or CDs anymore, and all my entertainment is paid for. I know all the alternative people at the other record labels, so we all pass along all our stuff to each other.”

11/20/89 (interning with Ross, who was recently laid off from Blast First Records, a British label distributed in the U.S. by Enigma) — He mentions that his CD player is broken, even though he has a bunch of CDs to listen to from his old days as a rep. He says, “I hadn’t seen a show in months that I had to pay for. Now that I don’t work for Blast First anymore, I don’t get any more free shows or records. I can’t afford to buy any CDs or go to any shows these days because I can’t afford to pay.

This trading of gifts as favors among the reps of record companies reveals how the norm of favor-reciprocity serves as a form of financial support to supplement the employees’ wages. It is one example of how employees shape the workplace culture to suit their ends, and how their employers allow this as a term of the negotiated order at Restless Records, Finally the extension of the norm of favor-reciprocity to other record companies suggests that the model of the Restless workplace culture might apply to other record company workplaces as well.

As I conclude, it should be mentioned that no culture, not even that of Restless Records workplace, remains static, and so I would like to mention some of the changes the company is presently undergoing and suggest how this might affect workplace culture. While Restless Records has remained committed to alternative music, its mother label Enigma has experienced considerable success in the mainstream commercial pop market. Enigma’s reputation as a record company with savvy for the music of the future has led to the recent acquisition of half its stock for $10 million by a major entertainment corporation.

As Enigma Records approaches its “adolescence,” as one employer deemed it, its success and expansion has affected the workplace culture. Enigma and all of its labels had only recently relocated to the two buildings in which I conducted my research. More capital has allowed the hiring of more employees, which in turn increases the need for more accountability and has ramifications for the informality permitted in the workplace. During my internship I attended the first intern orientation ever held at Enigma for all the interns of every Enigma label; the primary reason that it was held was the first theft at Enigma, including a fax machine and state-of-the-art audio technology. Thanks to this, the employers of Enigma finally felt the need to meet all of the interns, and they also took the opportunity to lay down policies which were previously never formally articulated. While the growth of Enigma is affecting Restless only slowly, such developments suggest that shared understandings at the workplace may be harder to maintain in the future. As such the dynamics of the Restless workplace may be due for change soon.

Finally, no participant observation would be complete without a few personal comments from the observer. Looking back upon my internship, I realize that I often experienced performance anxiety in the course of my tasks, which were usually explained to me once and left to my own trials and errors. From tracking Restless releases over the phone, operating the UPS postage machine, to soliciting the help of several employees just to fix the photocopier, I must have suffered dozens of minor anxiety attacks over why the most trivial tasks became so difficult. I realize now that some of this is due to my concern towards my work performance; I am presently continuing my internship at Restless in the hopes of stumbling upon some job opportunity after graduation either there or at another record company. However, my research helped me realize that many of my anxieties were, not surprisingly, the results of my attempts to discover the shared understandings which are embedded in every task. Restless Records, despite the image I might have portrayed is a busy workplace, and usually no one had the time to repeat to me how to do everything “correctly”. In fact, any notions of the “right” or “wrong” ways to do things are themselves shared understandings, and only through mistakes and errors did I come to grasp such understandings. Through this experience, I actively participated in the workplace culture as the sociological “other”; my experience at Restless Records was all the richer for it.

6 comments

Wesley Hein says:

Jan 28, 2014

Mara,

I love it.

Wesley Hein

Enigma Records

Leonard Nevarez says:

Jan 29, 2014

Thanks, Wesley. FYI, Mara didn’t write this essay — I did. She interned at Enigma the year before, and I’ll bet she recommended I give it a try when I was looking for an internship opportunity the year before. My 1989-1990 academic year interning at Restless Records was an exciting and unforgettable one.

So, what’s the status of Enigma Records presently?

Rich Soil says:

Apr 1, 2014

Hi, how are things going? Hope all is well. I’m a former artist from Restless Records. Just wondering, what is the phone number for Restless. Need to speak to someone there. Can you help me out? been trying and trying. Please..

Majors, Indies, and Internships | The Money Trench says:

Feb 20, 2014

[…] underplays the essential role unpaid interns play in startups, SMEs and independent record labels (even if they do call them ‘volunteers’). Focusing on large, visible corporations inaccurately […]

Ben Burton says:

Jun 4, 2015

Man, I want those Plugz CDs!

Leonard Nevarez says:

Jun 4, 2015

They are some of my favorite CDs, as you can read more about here.