Dream, dream, dream

It’s the eighties’ youthful theme

Loving the city

A theme for great cities

And loved ones

And love

– “Wonderful In Young Life” (1981)

Americans know them mostly as “that Breakfast Club band” from the 80s, but Scotland’s Simple Minds have carried on in one form or another long enough to enjoy a new critical appreciation. DJs have incorporated prominent samples from Simple Minds recordings into dancefloor bangers. The millenium’s postpunk revival restored the group’s dance-rock credentials; add cowbell to a track like 1979’s “Changeling,” step up the tempo a bit, and you’ve got a decent recipe for the Rapture’s 2002 “House of Jealous Lovers.”

To this retrospective, I want to propose the importance of Simple Minds’ urban aesthetic. It seems to me, and now I’m wondering why, those of us who came of age with UK music in the early 80s intuitively recognized Simple Minds as an ‘urban’ group, whatever that might have meant decades ago — a synth-based sound, their reign on nightclub sound systems, the pretensions of the new romantics and new Europeans, their penchant for pleated trousers. Yet I think there’s something more important to this question than just a long-standing obsession. As I’ll argue, today we all inhabit, to some extent, the urban world envisioned in Simple Minds’ early work.

To explore this issue, in this essay I examine the group’s urban aesthetic to show how it evolved in tandem with the musical developments of the group’s first six albums (recorded between 1979-84) and broader changes in urban geography and history during this first phase of the band’s career.

(I realize that most observers mark Simple Minds’ early career with the first five albums, which the band has recently taken to commemorating via the 5×5 tour and live recordings. However, I extend this period up through their sixth album, 1984’s Sparkle in the Rain, for two reasons. First, it’s the last to feature Derek Forbes, one of postpunk’s most creative bassists and a key contributor to their post-punk sound. And second, yes, I’m a new wave damage-case who still has a soft spot for this album, even though it points toward the direction that the group would pursue, in my estimation, with less relevance to pop music in the following years.)

Theme for great cities

Anyone who has held a Simple Minds album in their hands know that representations of the urban are plainly evident across various song titles, lyrical references and promotional visuals (the group never really exploited music videos successfully). But one of the most exciting qualities of Simple Minds’ music is that listeners can discern an urban aesthetic within the sonics of the music itself, without recourse to their visual or lyrical references. I’d say their urban sound is best captured by a number of songs from albums #3-4 — Empires and Dance and the two-record release Sons and Fascination/Sister Feelings Call — that reveal the foundation of two musical elements. First, the rhythm section is up front in the mix, anchored by Forbes’ throbbing, hypnotic basslines shorn of its high-end treble. Drummer Brian McGee’s style is simple but memorable, repeating spare rhythms of one or two bars’ length for machinic effect while generally eschewing cymbal crashes or drum fills.

Second, keyboardist Mick MacNeil dominates the mid-registers with clarion melodies on keyboard and organ, arpegiators looping one-bar synth figures, and beds of ambient chords and textures. In combination, these elements convey the musical sensations of motion and altitude — what Kerr evokes as airmobility (in “Sweat in Bullet”) — giving the listener a window seat on a trip through vast, technicolor landscapes. (From “Premonition”: Fly over land/Where no one’s heart can beat.) If this recalls the logic of German motorik groups like Neu! or Kraftwerk, or for that matter what it sounds like to drive into an immersive urban setting accompanied by any contemporary techno soundtrack, that’s no mistake. In a very significant way, Simple Minds’ early recordings comprise a key link between German krautrock and today’s techno urbanism.

Because bass, drums and keys comprise the most important elements of the early SM sound, it’s ironic and maybe telling that singer Jim Kerr and guitarist Charlie Burchill are the only original members left today. Not to diminish Burchill’s skill, but on these early records (specifically after their debut Life in a Day), his best contributions are almost indetectable to the listener. Like Irmin Schmidt’s keyboards in the German band Can, Burchill’s scratches, noises, embellishments, sustains, and melodies sound everywhere and nowhere at the same time.

Virtually synonymous with ‘Simple Minds,’ Jim Kerr is highly charismatic frontman who isn’t necessarily endowed with a recognizable voice (except for his occasional tendency to enunciate with curious stresses — uh-live and kee-king), nor shows special flair as a storyteller. In their early period, Simple Minds’ lyrics typically comprise abstract images ordered together with little narrative or perspectival coherence. Consider these verses from 1981’s “Love Song”:

Flesh of heart

Heart of steel

So well so well

I cut my hair

Paint my face

Break a finger

Tell a lie

So well so wellAmerica’s a boyfriend

Untouched by flesh of hand

Stay below it

Stay below

In glory days that come and go

Some promised land

In the cut-up tradition established in rock music by David Bowie, Kerr’s impressionistic montages let listeners reach their own individual connections — pretty much a normative lyrical strategy in postpunk. If their meanings are opaque, his words nonetheless sound good when sung; alongside the scattered, unsustained instrumental flourishes provided by MacNeil and Burchill, they add another tone to the increasingly complex sonic palette of this five-piece band. Kerr and the other members also have an intuition for when not to join in, which leaves crucial spaces in their arrangements and recordings. Tellingly, Simple Minds is probably the post-punk group with the keenest aptitude for composing instrumentals. Perhaps Kerr’s lyrical associations serve best as oblique prompts to his band, guiding their musical instincts away from conventional songwriting and pop maneuvers and toward more experimental directions.

Ambition in motion

The urban contains a multiplicity of social and spatial relations embedded in physical environments, social geographies, and historical eras. It’s impossible for any single individual to experience or comprehend these in their totality, much less for any one band to channel and convey them effectively within music. So which urban does Simple Minds’ early recordings occupy?

Simple Minds hailed from Glasgow, a bustling, gritty industrial seaport in Scotland, whose horizons the band quickly sought to transcend when they formed from of the ashes of punk pretenders Johnny & the Self-Abusers. Within a few short years the group realized these aspirations by establishing fanbases as far away as Canada, Australia and Japan. However, Simple Minds’ urbanism has a very concrete reference point: the European city of the 1970s and 80s. In its geographical scope, Europe represents the poles of estrangement and familiarity, of alienation and communion, between which Simple Minds’ urban aesthetic developed.

Europe and its cities connote several things within Simple Minds’ music, starting with a promising future to contrast with the economic stagnation and Victorian moralism beginning to sweep over northern England and Scotland in the 1970s. Germany was famously a source of inspiration to many post-punk groups. It gave rise to the musical influences and inspirations of Kraftwerk, krautrock, and other industrial/techno musics, while Bowie and Iggy Pop epitomized the possibilities of musical/artistic reinventions amidst urban squalor with which Berlin has long enticed Anglo-American beholders. But Simple Minds set their sights well beyond Germany to encompass the north Atlantic Benelux countries, France, Scandinavia, and the Mediterranean countries.

Two specific spatial relations tie this larger group of nations together in the band’s aesthetics, beginning with the activity of travel as the means to encounter other ways of living and reimagine the self. Simple Minds’ 1980 breakthrough single “I Travel” literally announces this ambition of the group: to pursue artistic development and commercial success through a frenetic recording schedule and, more importantly, an incessant itinerary of touring.

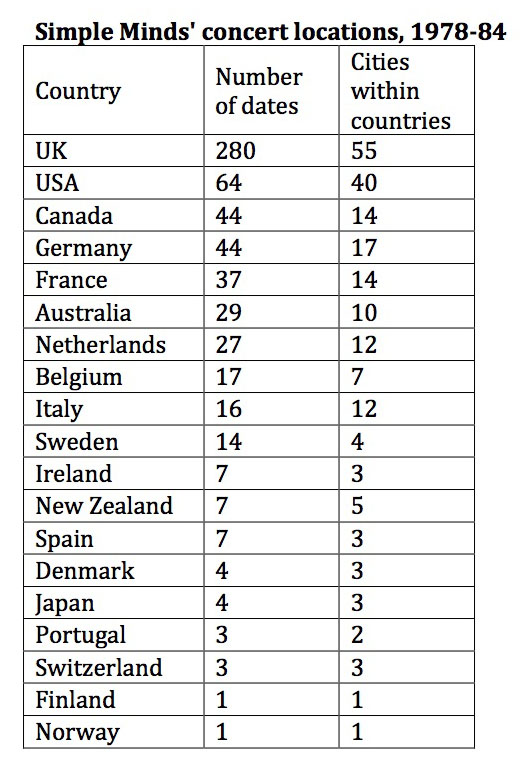

The second spatial relation involves the geography Simple Minds traveled through Europe. Consider this startling fact: the group played 610 concerts from when they began as Simple Minds proper in January 1978 to their final gigs with Derek Forbes in January 1985 (before their Live Aid performance). I haven’t checked to see if this is a record for any post-punk band, but it’s still a staggering feat: an average of over 100 concerts per year for six years straight.

Granted, this statistic is pushed upwars by the massive tours for New Gold Dream (125 dates) and especially Sparkle in the Rain (146 dates); the latter included a leg supporting the Pretenders through North America that was essentially Kerr’s honeymoon with new bride Chrissie Hynde. And as expected, Scotland and the rest of the UK dominate Simple Minds’ gig itinerary. The group never played outside the UK until October 1979 with a first date at Berlin’s Kant-Kino (commemorated by the instrumental “Kant-Kino” on their next album, Empires and Dance). Nonetheless, the level of touring to different countries and to different cities within those countries is remarkable. Quick: can you name 12 different cities in the tiny Netherlands? Well, Simple Minds played all of them — and then they traveled to some other Dutch cities.

In this phase of their career, the group generally headlined their own tours (with two exceptions, supporting Peter Gabriel in 1982 and the Pretenders in 1984) and played clubs and small theaters. By 1982, they began sprinkling in summer dates on the nascent European festival circuit: Roskilde, Torhout-Werchter, Pinkpop. (I saw Simple Minds headline the Werchter music festivals twice, in 1984 and 86, where they worked the festival stage and whipped up the crowd with the same skill as U2, their only peers among European audiences at the time.) They covered big cities often by playing two or more dates, either consecutively or on return legs.

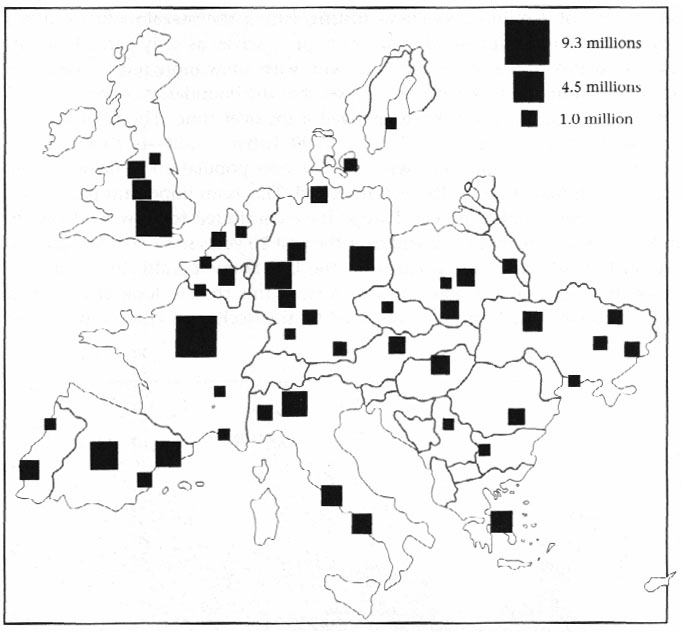

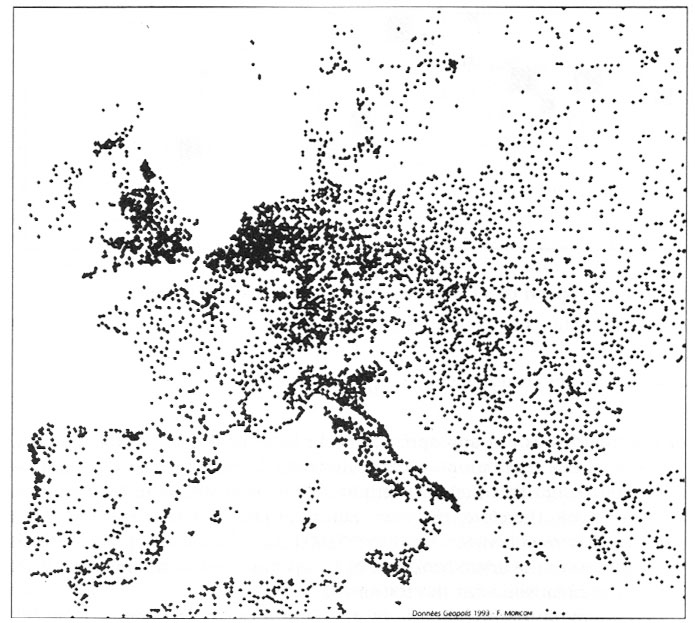

To put Simple Minds’ touring in some geographical perspective, look at the map below of European cities in 1990 with more than 1 million inhabitants. (I reproduce this from Patrick Le Galès’ book European Cities, which in turn incorporates maps by François Moroconi-Ebrard.) The data may be old, but 1990 is a useful bookend to denote the geography that Simple Minds traveled in their early career, with the exception of the reunited Germany. We see there were about 45 European cities with more than 1 million inhabitants in 1990, of which 15 lay behind what was then the “iron curtain” (which Simple Minds didn’t venture past until 1990).

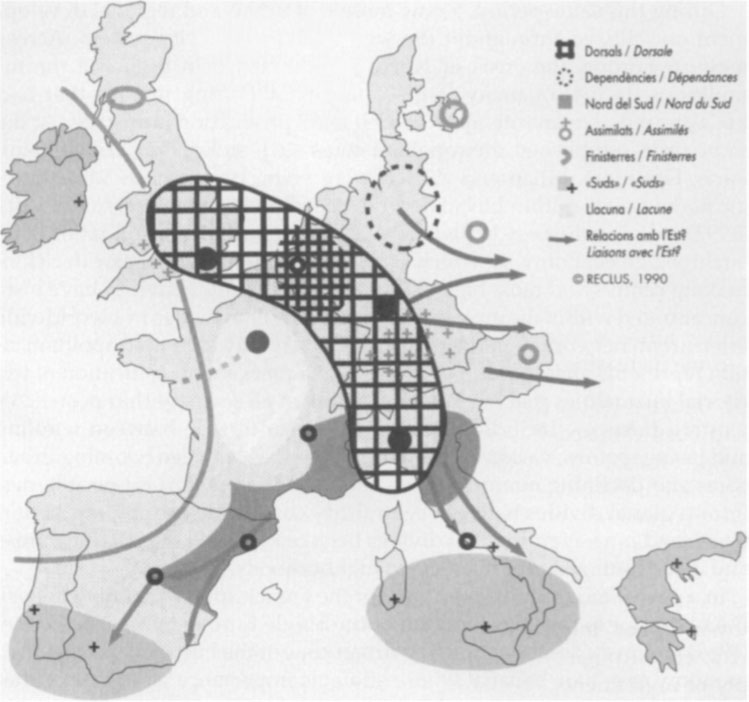

This leaves us approximately 30 cities in Western Europe, which provides a generous circuit for most rock bands’ Europeans tours — maybe too generous, if we want to emphasize Europe’s core urban zone. A 1989 analysis by the French spatial planning agency DATAR observed a so-called blue banana (shown in the map below, reproduced from a 2004 article by Neil Brenner) comprised of Europe’s key economic cities with regards to the economic and political integration promoted by the “blue” European Union. Notably, this geographical constellation bypasses Europe’s Romance language nations — no France, no Spain, and no Italy beyond the prosperous industrial cities of the north — and Scandinavia as well.

Now look at the table of Simple Minds’ tour destinations again: the group played 82 different cities in Europe between 1979-84. This suggests a more inclusive map of urban Europe, comprised of the approximately 3,500 towns of more than 10,000 inhabitants in 1990 (reproduced from Le Galès). By this measure, from 75 per cent to 85 per cent of Europe’s population lives in urban areas, depending on the country. (In comparison, the urban population in the United States is 20 per cent lower, as Le Galès points out.) For that matter, this map also reveals the hidden urban geography within the UK, particularly England — the backdrop to the 55 different UK cities where Simple Minds played in their first six years.

This last map reveals a different kind of European geography that we can imagine the group and its crew driving through in a van or later a tour bus for months at a time, covering smaller distances and reaching more places than the phrase “European concert tour” generally implies. Making no assumptions about the band’s sight-seeing habits, such a touring itinerary would necessarily reduce travel time and leave more time for local immersion and engagement with European towns and local residents than less extensive tours of Europe.

20th century promised land

Simple Minds’ peripatetic traveling and extensive geography comprises the experiential context for the group’s imagination and representations of European cities. To demonstrate how these evolved, I now take up the group’s first six albums in order.

Life in a Day and Real to Real Cacophony

Simple Minds’ debut Life in a Day (released in April 1979) is certainly the least classic of their ‘classic’ early records, introducing what sounds like a non-descript new wave unit plying fairly conventional compositions. Several tracks show the influence of Roxy Music, although the group’s lurch, Burchill’s barre chording, and MacNeil’s jaunty keyboards makes the Stranglers another reasonable comparison. Kerr frequently adopts a snotty, nasal vocal style that shows the influence of British punk — never a genre for which the band showed much musical or attitudinal affinity. Only the buoyant synth on the title track hints at the musical altitudes that Simple Minds would reach on subsequent albums.

A more important element on the debut album is the establishment of the essential theme in most Simple Minds’ lyrics. As illustrated below by “Somone,” the opening track, an alienated ego is drawn across a liminal or transformative space to a human connection via someone’s “calling.”

She says

Someone is calling

Someone is calling for me

She says

I got some feelings so different

No one else can see

She says

She says

Note the kinds of spaces depicted on Life in a Day: The children from the street call out my name (“Murder Story”). Into the street/People can meet/Don’t turn your back to the view (“All For You.) I’ve seen the streetlights/Shine on the underground (“Pleasantly Disturbed”). I see them walking/You know they’re walking at night/Oh in the dark you know/They’re shining out so bright (“No Cure”). Is it true you’re running round?/Now is it true they’re calling you the Chelsea Girl? (“Chelsea Girl”). The street, the underground, the dark, streetlights at night — these are clichéd backdrops for punk’s urban youth revolt, albeit rendered uncanny in the sci-fi style of Gary Numan (“Down in the Park”) and Joy Division (from that group’s “Shadowplay”: To the centre of the city where all roads meet/Waiting for you).

Recorded in September 1979 with the same producer (John Leckie), the second album Real to Real Cacophony saw the group jettison almost all of their debut’s punk or new wave influences to develop a more original, innovative sound. The album’s styles are eclectic, its strategies varying track by track (including three instrumentals), but it set Simple Minds down a sure path from which they would never look back. MacNeil’s keyboard takes center stage, while Burchill largely eschews riffing (the monster “Changeling” notwithstanding) to concentrate on texture. Real to Real Cacophony also shows a newfound fluency in dance rhythms, with “Premonition” laying down an ominous groove as compelling as that of any Factory Records band.

Otherwise all over the place lyrically, a pair of themes emerge on Real to Real Cacophony that would reach fuller expression on the next two albums. First, the closing track “Scar” yields Simple Minds’ first explicit travelogue: Kerr narrates an auto voyage into a cityscape that promises hidden meanings, before reaching an end practically ripped from the pages of J.G. Ballard’s Crash. Second, “Citizen (Dance of Youth)” introduces a geopolitical critique with its depiction of life under a totalitarian regime as seen from a divided city (most likely Berlin: An American/Got got a camera/Takes a picture).

Citizen

The state that we’ve come to love

Love’s a crime against the state

I hate the sound of bells

Communications lost

Something we’re after

I hate democracy

One more contact lost

Empires and Dance

1980’s Empires and Dance, Simple Minds’ third album, is a chilling yet danceable album — an essential contribution to the post-punk canon by a highly confident musical unit. The first track “I Travel” launches with a manic loop of whirring electronic noises before exploding into an amphetamized rush of Kraftwerkian proto-techno and Moroderesque eurodisco (with Forbes echoing the bassline from Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love”). Suddenly, the album shifts into dystopian, minor-key territory, as massive, almost oppressive rhythms (especially on “Celebrate, “This Fear of Gods” and “Thirty Frames a Second”) tune the listener into Orwellian scenes of state control and elite exploitation.

Or so it seems to me. In moods and lyrics, Empires and Dance demonstrates a narrative coherence missing on Simple Minds’ prior albums, although Kerr’s abstract imagery allows at least two possible interpretations. “If there’s any kind of concept to Empires And Dance, it must be the boy or man who’s run away — a fugitive,” Kerr has said, but the international touring that the band had dove into also supports a geopolitical framing.

I was twenty, and I looked around me. We had the talent always to be in the place where the neo-Nazis exploded another bomb. Bologna, a synagogue in Paris, a railway station in Munich. Don’t tell me anything like that could leave you unmoved.

The album cover displays a photograph by Michael Ruetz from his series on the Greek dictatorship of the 1970s; an ersatz cyrillic font and titles like “Constantinople Line” suggest forgotten circuits of authoritarianism and brutality laid down in a long history of western empire. From “Celebrate,” The road is long/Seven thousand miles/Soldier talk/And uniform; on “Thirty Frames a Second” we hear of conflict between Young immigrants/And legionaires. Although Kerr refrains from delivering explicit manifestos or political analyses, Empires and Dance devotes considerable attention to themes that will further develop through the remainder of Simple Minds’ first six albums.

The first is a view of internationalism as a Babel of diverse tongues and cultures, united only by a purposeful failure to understand the other. Europe has a language problem/Talk, talk, talk, talk, talking on, he sings on “I Travel,” later diagnosing America and Asia with the same problem. A first-class rail passenger looks down upon new boarders of the titular “Constantinople Line”:

Hey Waiter,

I’m first class.

Hey Waiter,

Where are we now?.

Am I last?

Am I last?

Hey Waiter,

Don’t talk back.

These tenants speak

A traveller’s language

Caucasian talk

They’re saying nothing

I see a land

As we crawl by night

I see a face

In the window in front

These stations are useful

These stations we love them

Newspaper

Encounter

Confusion

This stanza also illustrates another theme, the compulsion of movement, epitomized on Empires and Dance by references to modes and way-stations of travel and transit. This train is late/I hesitate/To a city that they live on, Kerr observes on “Capital City,” but his narrator is seduced by movement: Pulse/Feel/Pulse. I always took the echoing French female voice in “Twist/Run/Repulsion” to be an intercom announcement in a busy European airport, which made sense in juxtaposition with Kerr’s mumbles of preoccupation; in research for this essay I learned that the voice is actually reading from a short story in French by Nicolas Gogol about the main street in St. Petersburg. This alternate interpretation is still thematically consistent, however, since ‘the city’ is represented here as a site of travelers’ superficial, ironic assessments, not a place of sustained cosmopolitan engagement. From “I Travel”: Love songs playing in the restaurants/Airport playing Brian Eno.

A third theme is skepticism about formal international cooperation, as marked by a first reference (more would follow on the next album) to the League of Nations, the failed pre-WWII precursor to the United Nations. These reptiles scream/A violent party/All art and jazz/And League of Nations, the first-class bigot announces in “Constantinople Line”. On “I Travel” Kerr observes Euro-Bureau-Interpol/Making love to the criminals.

Granted, these songs may contain unreliable narrators, and more generally no theme on Empires and Dance are invulnerable resist semantic instability and intertextual contradiction. Kerr’s skill as a lyricist on this album really lies in his litany of concrete details of urban environments and geographic mobility, beheld impressionistically in a rapid, even explosive montage that Italian futurists could recognize: Travel round/I travel round/Decadence and pleasure towns/Tragedies, luxuries, statues, parks and galleries. Simple Minds’ most extended meditation on cities, Empires and Dance remains their most symbolically resonant work.

Sons and Fascination/Sister Feelings Call

On an artistic streak after months of further touring, Simple Minds rushed themselves once again into the studio with a new label (Virgin) and producer (Steve Hillage). So much material was recorded that the band opted to put in out two albums released simultaneously. Per custom, I regard Sons and Fascination and Sister Feelings Call as a single album, Simple Minds’ fourth, although Sister Feelings Call is shorter and less developed — for example, its “Sound In 70 Cities” is simply an instrumental version of Sons and Fascination’s “70 Cities As Love Brings The Fall.”

The glut of material explains why some fans and critics view the fifth album as underbaked and in need of editing, at least when compared to the albums that preceded and would follow it. If anything, I think this makes Sons and Fascination/Sister Feelings Call the most underrated of Simple Minds’ first six albums. Yes, not all of these tracks work equally well (true perhaps of all Simple Minds albums), but precisely because the tracks are less composed, they function more as soundtracks with all the emplacement of the listener into psychogeographic settings that this form entails. (Stated differently, Sons and Fascination/Sister Feelings Call sounds fantastic when driving in a car.)

Sons and Fascination/Sister Feelings Call is also the key transitional album in Simple Minds’ catalog. On the one hand, there are clear sonic and thematic similarities with Empires and Dance. The cover photos juxtaposing blurry movements of cars and people before the immobile band members convey the familiar compulsion of movement and mobility. There’s a continuing geopolitical criticism, now with new attention to America, where the group had just toured a second time. (Kerr manages a Brecht quotation in “20th Century Promised Land”: Unhappy the land that has no heroes/No! Unhappy the land that needs heroes.) “Sons and Fascination” and the almost-instrumental “League of Nations” put a drum machine to the service of ominous modernism familiar from Empires and Dance. And of course, the fourth album further pursues dance grooves on the spiky “Sweat in Bullet,” the effervescent “Love Song” (that tambourine on the chorus!), and the ethereal “Theme for Great Cities.”

On the other hand, a shift in mood on Sons and Fascination/Sister Feelings Call signals the emotional blueprint of the group’s future recordings as Simple Minds venture into more complex major/minor-key sequences, uplifting moods, and a new sense of epic scale. The opening track “In Trance as Mission” announces this new direction. A foregrounded bass and drum playing a 6/8 motorik rhythm lay a foundation for a subdued bed of synth swells and guitar feedback. For just one moment in time/I hear the holy back beat: in a becalmed baritone, Kerr recites a litany of spiritual visions seen in a new type of light. Burchill’s guitar chirps melodically, evoking seagulls soaring through a dusky sky as the narrator observes Something crashing against white rocks. This serenity is undermined only by hints of a familiar restlessness: No calm to my hand… You’ve got to move on…

With Sons and Fascination/Sister Feelings Call, a new vocabulary became necessary to describe the kind of sublime moods and wide-angle, naturalistic vistas expressed on tracks like “In Trance as Mission” and “Seeing Out The Angel.” While the group would refine these aesthetics on New Gold Dream, their next album, elsewhere the group develops a post-postpunk rock that would be further realized on the sixth album, Sparkle in the Rain. Thunderous drums and sustained guitar distortion on “70 Cities as Love Brings the Fall,” “Boys From Brazil,” “The American,” and “Wonderful in Young Life” signal how capably the group has rivaled or surpassed the achievements of other guitar groups of the time — the Skids, Echo and the Bunnymen, and yes U2 — in exploring a yearning, unironic rock.

The urban aesthetic appears a bit harder to discern from Kerr’s abstract, indetermine language. Gone are the European settings narrated on the last album; on “In Trance as Mission,” a nameless city and a statue in fog are the only defined objects in the spiritual vista Kerr describes. “Theme for Great Cities” of course is completely without lyrics, while that title gets name-checked in another song, “Wonderful in Young Life” (quoted at the beginning of this essay), a vaguely Whitman-esque paean to youth, love and dreams.

So what is urban about Sons and Fascination/Sister Feelings Call? Maybe a better question is, where are those 70 cities in which love brings the fall, anyway? In fact these could be any cities. Tellingly, in live performance Kerr would rattle off any number of place names familiar to concertgoers in an added stanza. What the phrase “70 cities” really connotes is a broader affiliation of musical communion that transcends the narrator and listener, as forged in the actual bond between the group and its audiences.

I should add that by this point, Simple Minds and Kerr in particular had become rather capable and powerful in concert. In part this reflected new commercial and artistic ambitions (an occasion for a change in record labels); in other part it resulted from the considerable touring experience under their belt. Recall from my earlier discussion their extensive penetration of the UK and Europe circuit that sent them out to far-flung locations. Such efforts not only were paying off by this point, in terms of developing a growing fanbase and shedding the group’s cult status, but provided the experiential basis for the unexpected spirituality that the group was beginning to express. The lyrical affirmations that began to creep into Simple Minds’ music — love, dreams, beauty and so on — doubled as performative utterances, as if by saying these things in performance, Kerr made the musical communion of the audience real. In turn, ‘the city’ is what Kerr names this exuberant collective.

New Gold Dream (81-82-83-84) and Sparkle in the Rain

Simple Minds wound down their urban aesthetic with two very different albums. New Gold Dream (81-82-83-84) was the commercial breakthrough, with two singles (“Promised You a Miracle” and “Glittering Prize”) contributing valuably to 1982’s closing “New Pop” chapter in post-punk. This album remains the group’s artistic zenith, using quieter volumes and softer textures to convey a romanticism and spirituality at no expense to groove. Central to the album’s dynamism was the replacement of drummer Brian McGee by a trio of experienced drummers, the most important being his permanent replacement Mel Gaynor, who introduced an intuitive swing, improvisatory fills, and unmistakeable finesse (listen to that cymbal work on “Someone Somewhere in Summertime”) to the group. It’s no coincidence that the irrepressible title track was initially called “Festival Wave,” since New Gold Dream saw Simple Minds graduate musically and commercially to the status of arena rock. Their big-sounding music had finally found a home in correspondingly big venues, yet the group never resorted to arena rock’s traditional force or ham-fisted gestures to realize their epic scale.

Alas, the same can’t be said for 1984’s Sparkle in the Rain, which reasonably deserves the “U2 with keyboards” comparison that had begun to tag Simple Minds. The album has its high points, certainly more than any Simple Minds album to follow, and MacNeil in particular gives inspired performances on “Waterfront,” “Book of Brilliant Days” and “White Hot Day.” Disappointingly, Burchill released the repressed rock guitarist from the band’s debut, perhaps egged on by Gaynor’s pounding attack. (Matters weren’t helped by the cluttered, muddy production of Steve Lilywhite, who couldn’t find the sonic clarity he had just achieved with U2’s War.) And while I can say from firsthand observations at a Belgian disco in 1984-85 that people danced to the singles off Sparkle in the Rain, it sure wasn’t pretty; with this album, Simple Minds left behind their Eurodisco rhythms and any remaining postpunk spirit once and for all.

Significantly, with both New Gold Dream (81-82-83-84) and Sparkle in the Rain, Simple Minds also abandoned the modernism that had fueled their urban aesthetic to this point. Musically, New Gold Dream sounds fantastic, which I mean literally; the band puts such a dreamy sound in service of such emotionally engaging melodies that the listener can’t help but feel transported to imaginary environments that are less sci-fi and more magical (“Colours Fly and Catherine Wheel”), less urban and more edenic (“Somebody Up There Likes You”). Lyrical references to cities on New Gold Dream are few, nondescript, solely metaphorical, and immediately followed by an elemental references, as if to hold cities equivalent to natural forces in the group’s romantic language. Once more see city lights/Holding candles to the flame (“Someone Somewhere in Summertime”). And the world goes hot/And the cities take/And the beat goes crashing/All along the way (“New Gold Dream”). (This begs the question, just what do cities “take”? Take in? Take on?)

The eclipse of the urban by nature advances further in Sparkle in the Rain, which is replete with references to rain, the sky, fire, moon, day, storm, shadows, time, and so on. “Up On The Catwalk” name-drops several cities, ostensibly to convey the universality of love, tragedy and hope among a planetary community:

Up on the catwalk there’s street politicians

That crawl in from Broadway say then “Who are you?”

And up on the catwalk there’s one thousand postcards

From Montevideo say that I’ll be home soon

Get out of Bombay and go up to Brixton

And look around to see just what is missing

And up on the catwalk, girls call for mother

And dream of their boyfriends

And I don’t know why

Simple Minds’ last truly great song, “Waterfront,” finds Kerr dwelling in and upon one city in particular: Glasgow, the band’s hometown. Yet while the vocalist talked in interviews about how the song originated with his return to the shuttered shipyards that his grandfather worked at, this urban story is stripped of any mention to Glasgow and rendered universal: Get in, get out of the rain/I’m going to move on up to the waterfront.

As Simple Minds pursued a metaphysical lyricism and a dynamic sound suited to moving thousands of people, their songs lost their sensitivity to concrete environments and real urban life. A telling example is Sparkle in the Rain’s cover of Lou Reed’s “Street Hassle,” originally a three-part suite about the life and death of a New York City junkie-transvestite. With his famous ear for dialogue and detail, Reed zeroes in on the lusts and profanities of the underworld: But when someone turns that blue/Well, it’s a universal truth/And then you just know that bitch will never fuck again. In their version, Simple Minds edit “Street Hassle” to its first part (“Waltzing Matilda”), scrub the lyrics of their queerness and lasciviousness (gone is the line what a humpin’ muscle), and set the remaining story of orgasmic communion to a flashy exercise in rock dynamics. The incongruity of a final remaining profanity, the ambiguous line just like she had never come, only underscores how the tone and scale of Simple Minds’ new music was at odds with the urban everyday.

Simple Minds’ epic turn is made graphic on the covers of their fifth and sixth albums. New Gold Dream features a large cross with burning heart and ancient book (the bible?) at its center; a gauzy background suggests a stone wall in the mists — a ‘new medievalism,’ perhaps. Sparkle in the Rain shows a coat-of-arms depicting (ahem) sparkles in the rain in one quadrant and the group’s initials in another; on either side, banners encircle lances of two-bar crosses, interpretable as both variants on the initial M. and derivations of the cross from New Gold Dream.

And how do I feel living in the 80s?

This recognizably European iconography frames the final development of Simple Minds’ urbanism. From the clichéd punk streetscenes of Life in a Day to the geopolitical travelogues of Empires and Dance to the spiritual visions begun on Sons and Fascination/Sister Feelings Call, the alienated ego at the core of Simple Minds’ early lyrics has always been searching for “someone, somewhere.” By the fifth and sixth album, it appears to have found its home in a Catholic conception of Europe. By this I don’t mean the Catholic, generally Romance-language nations of Europe or in particular communities and fellowships that practice Catholicism. The spiritual imagery of New Gold Dream and Sparkle in the Rain has actually been a bit of a red herring, as Kerr has pointed out: “No one in the group practises religion, but most of the band are Catholic. I think you get stamped with that when you’re young and it’s there forever, you can’t really escape it.”

Instead, what Catholicism symbolizes in Simple Minds’ music is the inclusive collective that reintegrates the alienated ego. This symbolism has material basis in the group’s career, as the evolution of the group’s themes of searching for connection coincided with their tours of Europe and the increasingly larger, rapturous crowds they played to. Having seen Europe through an initial lens of unfamiliarity and estrangement (best captured on Empires and Dance), Simple Minds eventually found in Europe the familiar — a common nature, even a pan-European ‘citizenship,’ activated in each successful performance. Admittedly, the terms to this ‘citizenship’ are unclear and vague. Simple Minds’ music tends to emphasize the experience of belonging: an exuberance that resolves their first four albums’ mind/body dialectic — i.e., a ‘fascination’ with real places set in tension with incessant physical/spatial motion — into a transcendent, celebratory and (most unfortunately) no longer danceable form of stadium rock.

Of course, having achieved this particular musical and semiotic synthesis, this is about the point when many fans believe the group became uninteresting and stopped developed artistically, except to release some well-meaning political anthems (“Mandela Day,” “Belfast Child”); to see Forbes, MacNeil and Gaynor leave the band for long stretches or permanently; and, by the new millennium, to betray anxiety over their diminished commercial status. However, the European citizenship expressed in Simple Minds’ early work has a cultural significance that outlives the group’s vitality. To appreciate this, we need to recall the historical context of 1978-84.

For many, the ‘European community’ at this time would more likely denote NATO (the North Atlantic Treaty Organization) than the European Union. The latter had only 12 member nations in 1986; the Euro, the single-market Eurozone, and the relaxation of passport controls at international borders were but plans until the following decade. European youth would more likely regard geopolitical institutions through the framework of the Cold War and its conditional extension of citizenship’s rights and freedoms (military conscription wasn’t abolished in most major continental European nations until the new millenium). The middle albums of Simple Minds’ early period, particularly Empires and Dance and Sons and Fascination/Sister Feelings Call, speak to this geopolitical/militaristic anxiety quite clearly: What’s your name?/What’s your nation? (“This Earth That You Walk Upon”). And yet Simple Minds’ political agenda, if you will, has been to envision a more affirmative and inclusive vision of European community, one which escapes the narrow ‘realism’ of an anxious era. This community would be invoked on New Gold Dream and Sparkle in the Rain and convened as a practical matter with every audience held skillfully in Kerr’s hands.

Where do we find Simple Minds’ vision of European community today? The group leaves an ambivalent legacy. It can be argued their Catholic and pan-European imagery draws on a symbolic imagery that has resurfaced in post-9/11 anxieties over ‘civilizational’ conflicts between Europe and Islam. Considering this is the band that played Live Aid and wrote a song called “Mandela Day,” I tend to give Simple Minds the benefit of the doubt where claims of retrograde cultural/racial politics are concerned. Yet their iconography is admittedly ethnocentric in its connotations.

I think a more relevant connection can be drawn from the group’s UK origins, from which Europe provided an obvious and geographically accessible site of artistic reinvention; their skepticism of state institutions and Cold War militarism; and their aesthetic/career embodiment of spatial movement. Combined, these promise nothing less than the EU’s vision of a continent without war, united through the free movement of people, goods and capital. Is this not the European utopia realized by, say, any DJ from England or Spain who moves to Berlin to spin techno? (While there, be sure to snap a photo of the original Kant-Kino!)

For some commentators, the circulations and concentrations of capital promoted by EU policies consolidate a neoliberal urban hierarchy of fortune and underdevelopment — world cities at the top, industrial outposts and small towns at the bottom. But recall, one final time, the urban Europe (pop. ≥10,000) that Simple Minds has retraced on tour and in symbolism — the especially southern and central Europe of visible history, local customs, grand places, town churches and outdoor markets. This romantic geography of travel and residence off the beaten path is the Europe of Simple Minds’ urbanism, not the interchangeable major cities of the blue banana. Today it’s the Europe accessed via what sociologists Michaela Benson and Karen O’Reilly have called lifestyle migration, or what I would call quality-of-life migration — a geography of individual freedom and mobility, unencumbered by frictions of states or histories. It’s the Europe Kerr himself lives in today.

JIM KERR (MAY 28, 2012): Most groups can usually recall specific gigs that for some reason of importance were “career defining” or “career changing” for them. In our case there are quite a few, notwithstanding our first ever gig of course. After all, it is said that every journey begins with a first step. However a few gigs, due to consequences, perhaps mysterious and therefore unforeseen, actually became “life changing” as a result of them having taken place. And well, next month marks for me the anniversary of one of those gigs in particular.

The show I refer to took place almost 30 years ago in a smallish, outdoors sports arena, situated near the harbor front at the port of Messina. It was to be my first night in Sicily, a place that at no time prior had I given much thought to, or at least so out with the context of Francis Ford Coppola’s award winning Godfather movies. But lo and behold, some kind of magical seduction seemingly took over me when I set foot in Sicily for that first time, and as some might already know, a whole three decades later and as a result of that first gig, I am still there. (Or at least I am still there very often when not on concert tours, or writing and recording with Simple Minds and Lostboy! AKA.)

I don’t have a place that I call home and it has been that way for a decent amount of time. The main reason I have no home is that I don’t spend enough time in one specific place for me to feel like it is really my home. Sentimentally speaking, Scotland of course will always be “home” for me. It is where I grew up, is to where I will always feel that I belong. I am quite sure of that, but the reality is that for most of my grown up life I have not lived there enough for it to be my home as I am neither based or work from there.

All of which brings me back to Sicily, because in the absence of having any real physical home, Sicily has been a kind of on-off sanctuary for me, it is quite definitely my spiritual home and continues to be so even decades later. Or it is as long as we agree that the definition of “spiritual home” is: A place where you feel you belong, although you were not born there, because you have a lot in common with the people, the culture, the landscape and the way of life.

And what was it about the gig in Messina all those years ago that influenced such an outcome that led to Sicily getting under my skin and into my heart? Well, I could write a book on what happened during my first 48 hours in Sicily. I could explain how Taormina floored me with its charms in a way no place has done quite since. (Kyoto in spring comes close though.) I could also hint at many other things that came to pass in a couple of days that then led me to make my base within striking distance of Mount Etna. But much of that would be way too intimate, relevant only to me for the most part.

So let’s just say that it was the fact that the gig occurred, otherwise in a busy schedule that has kept me active all of my working life, I might not have found my way yet as a tourist to this most southern tip of Europe. And with that being so I might have remained in the dark with regards to a place that has brought so much mystical light to me.

[Special thanks to the Dream Giver website for Simple Minds history and lyrics. And yes, I’ll be at the Simple Minds concert in New York City on October 24, their first in over a decade. Hit me up if you’re going!]

![Simple_Minds_-_Sons_And_Fascination-[front]-[www.FreeCovers.net]](http://pages.vassar.edu/musicalurbanism/files/2013/08/Simple_Minds_-_Sons_And_Fascination-front-www.FreeCovers.net_.jpg)

14 comments

Martin Valentine says:

Aug 18, 2013

Brilliant, wonderfully written piece! But I must disagree with you on the ‘everything 1985+ is rubbish’ argument. It simply isn’t true. Listen to Once upon a time again – it’s far, far weirder than any other mainstream album of the time. And this is a band that is still working hard and still making quality music – the great lost album Our Secrets Are the Same from 2000 is as beautiful and atmospheric as any of the early stuff…. And nobody, anywhere has made a song as beautiful as 2009’s Light Travels.

I’ve seen Simple Minds 74 times in 10 countries since 1984 – and they are playing better now than at any point in that period. I’ve seen places and met people I would never have had the chance to without having this band at the centre of my life – so I strongly identiy with what you write!

Leonard Nevarez says:

Aug 18, 2013

Thanks for the suggested listening; I’ll try to give the later eras another try. Much of that mid-period material is hard to find in the U.S. without paying import prices or downloading illegal MP3s, neither of which I’ve been interested in. Maybe I just lament the absence of Derek Forbes and Mick MacNeil, two of my favorite new wave players.

Post-Punk Monk says:

Sep 19, 2013

My two cents on “Our Secrets Were The Same?” Simple Minds “heroin” album! It starts off okay but quickly loses energy and focus. I don’t blame Chrysalis for spiking its release! For the good material of the last 20 years, stick with the following:

• Good News From The Next World – Mainstream but it sounds exciting from start to finish.

• Neapolis – Where the band re-connect to the Krautrock that informed their earlier breakthroughs again for the first time. They have released better albums since, but at the time this one reminded you of the band that made Sons/Sister. Derek Forbes was back, but tellingly, he has no writing credits. A shame, since Simple Minds glory years came from the jams that Forbes would lead with those commanding bass lines.

• Cry – Kerr/Burchill have only two writing credits on this album. Most of the material was written between Jim and Italian DJs who had great respect for the early years. Vibrant and eclectic, it remains my favorite SM album post “Sparkle In The Rain.” The best thing about the album is that it is a move away from rock to pop/dance for the first time in years for the group.

• Black + White 050505 – Starts off with “Stay Visible” the best song in the last 20 years [up to that time] which actually sports a killer bass line for the first time since Forbes was drummed out. But the energy level peters out midway until the thing literally drags itself to its conclusion. Insert heavy sigh here.

• Graffiti Soul – I don’t like it more than “Cry” but it is more consistent. It’s almost as good to me, but I’d understand those who liked it more than “Cry.” The opener “Moscow Underground” is utterly amazing. Especially since Mel Gaynor really steps into McGee’s shoes for some light, dazzling motorik drumming that gives the tune its Krautrock heartbeat. All of the songs are fantastic.

mary says:

Aug 27, 2013

Thanks for this piece! really thanks. Brilliant, easy, fresh and.., exhaustive! and politically interesting. I didn’t read anything written in this way till now. And yes, I’ll be there and I’ll come from Italy!

Spider Moccasin says:

Sep 17, 2013

How shocking and disappointing it really was to slowly collect the early Minds LPs and fall in love with the “urban” material, only to see them live at last in fall of 1985 playing their stadium “gospel” dog and pony show.

How easy it was to discard the Minds as the eighties ended, somewhat embarrassed by their transformation, and totally uninterested without Forbes and Macneil’s contributions.

How exciting its been to fallback in love with the first six albums all over again over the last two years, and hearing about the 5X5 tour, so unavailable as performance or recording to us devoted fans in the States.

And how uninterested I am in supporting another American tour of their awful hits, when all I want, and have ever wanted, was 5 X 5 material performed live here in Portland, Oregon, USA.

How satisfying this essay was, the best yet about my favorite period of a disappointing yet genius band.

Post-Punk Monk says:

Sep 19, 2013

Aaaaah, Simple Minds. How they vex and beguile me by turns through my 32 years as a fan. I am in complete agreement that the first six albums are an unparalleled career arc in music that I love even more now than when they were still fresh in the world. What a bitter disappointment, then, was what came afterward.

I’ll never forget the first time I heard “Alive + Kicking.” It was on the FM rock station that was playing in the darkrooms at the University I attended. First of all, it was a shock to hear the new Simple Minds track on the radio since I was used to buying their latest sounds on import single that were NEVER played on the air. After THAT SONG, everything had changed. I was treated to a song that was a far, far cry from the experimental sounds of their early days or even the conventional [but exciting] rock they had recently trafficked in. Since it followed “Don’t You,” it was a top ten hit of shame for the band.

At this point it was finally possible for me to see the group live in 1986. It’s a fine kettle of fish, when after liking a group for five years in the wilderness, you finally get to see them when they’ve just released their big, bad sellout album. I thought I’d go to the show anyway since this would in all probability be the first and last time I ever got to see the group. And after all, they couldn’t ignore their entire previous and excellent repertoire in any case. Jim Kerr looked his usual jerky self wearing an appalling outfit and acting as stiff as ever in concert. Derek Forbes wasn’t there so I really had to ask myself why I was. The setlist never once touched past New Gold Dream material save for the encore medley where they blended “Sun City” with “Dance To The Music” and their own “Love Song” for a few tantalizing bars. Put bluntly, Simple Minds were bloated dinosaurs at not yet 30. An embarrassment to the band they once were. They were entering the American market at the sports arena level and it was a hideous thing. I don’t really have any memories of the show itself, only a lingering [to this day] sense of disappointment. I knew what I was getting into by going to the show and I have no one to blame but myself.

Their next several records scraped even further into banality and I only got rewarded with the vibrant [if mainstream] “Good News From the Next World” in 1994. This was an album that actually made me want to see them agin in concert, but that took another eight years. But the albums that were released in the last 20 years at least show the band trying, to various degrees, to reconnect with the mojo that propelled the substantial career arc of their first six albums. “Cry” and their last one, “Graffiti Soul” were excellent! It’s been gratifying to see the change of attitude that Kerr and Burchill show towards the music that might not have made their material fortunes, but certainly made their artistic ones. That there was actually a 5X5 tour [that I would have paid a kidney to see with Derek Forbes on bass] speaks volumes on how far from the darkness of their arena years [’85-’93] that the band have travelled recently.

Come next month, I’ll be in the 9:30 Club eleven years after the last time and I’ll be seeing a band that will in all probability be even stronger than the one that frankly thrilled me to no end in 2002 with material like this in their set list:

Simple Minds – 9:30 Club 2002

main set

1. New Gold Dream (81,82,83,84)

2. I Travel

3. Speed Your Love To Me

4. One Step Closer

5. Love Song

6. See The Lights

7. Hypnotised

8. Glittering Prize

9. Ghostdancing

10. She’s A River

11. Spaceface

12. Someone Somewhere (In Summertime)

13. Belfast Child-Waterfront

14. Don’t You (Forget About Me)

encore

15. Theme For Great Cities

16. New Sunshine Morning

17. Promised You A Miracle

18. Sanctify Yourself

19. Alive And Kicking

Just looking at this set list raises the hairs on the back of my neck! What a dramatic difference from the previous time I had seen this group in 1986. The group that I took great pains to see then were 16 years younger but seemed 30 years older. The group on offer in Tampa in 1986 were old men before their time – a veritable disgrace to the once proud name of Simple Minds. That show featured exactly 1/3 of a song that I was really excited about [“Love Song”], a handful of tracks from “New Gold Dream” and “Sparkle In The Rain” [not my favorites from those in any case] and finally, most of the weak “Once Upon A Time” album. That evening in 2002, in comparison, was an embarrassment of riches! With virtually every tune a classic or at least an example of greatness, the band played like they were 20 years younger and still eager for adventure. Against all odds, and after a decade of evidence to the contrary, Simple Minds were once again a band with a future. And I’ve been waiting for another shot to see them ever since.

Leonard Nevarez says:

Sep 19, 2013

I’m getting a big kick out of this discussion — thanks for reading and responding generously to my essay. Rather than take one side or the other, I might just point out that (at least here) the defenders of Simple Minds’ post-1985 work seem to come from the UK and Europe, where the band’s recorded material has remained available all these years, while the critics seem to come from the US, where it hasn’t. The point of my essay is that there’s necessarily something ‘European’ about Simple Minds’ appeal, but is there also a technological/publishing context to our differing opinions? Maybe we Americans are disappointed by Simple Minds’ later albums because we had to look so hard for them?

Post-Punk Monk says:

Sep 19, 2013

The first six are so good, that I was happy to look hard for them! Even after ’85-’91! That’s how high I hold them Simple Minds in esteem. But I know what you mean. I met guys in the 90s who should have been SM fans, but had never heard anything pre-Breakfast Club. I delighted in exposing them to the early material. And even back in the day they were an exotic band forThe States. I read about them in the UK press and there were comparisons to all of my other favorite bands who were somehow easier to find records from, so after reaching a point of no return, I bought the “Sweat in Bullet” 2×7″ unheard which offered four songs for $3 as an import single, and hopped on the SM bus for good at that point, being current as well as grabbing all that came before.

Spider Moccasin says:

Sep 19, 2013

I think devoted American fans did not struggle to locate post 85 material at all. They were instead put off greatly by the evangelical transformation of formerly respected post punkers like Kerr and Bono. My peers much rather preferred SM’s exotic travel lyrics and vague editorials about different political, social, and economic climates in far away lands, especially near the Iron Curtain.

It seemed just as the Berlin Wall came down, SM lost credibility to American devotees with their blatant grab at political relevance, preaching about apartheid to our nation, with its own troubled history. Along with the crucifix on the cover of an album all about money and greed as a measure of success, SM appeared to non religious American fans to have sold out, cashed in, and quickly lost their credibility.

American fans found the earlier oblique SM lyrics far more satisfying because they didnt preach, judge, or condemn as much as they probed, questioned, and forgave. As Kerr moved towards human rights issues like apartheid, yanks drifted even further, repulsed by their own guilt (that nagging history of red genocide and black slavery perhaps), and found more relief in the new grunge that pushed aside all the hair metal and new wave romantic acts wearing make-up and moussed hair. Such Irony died, replaced by Rage.

As Bono, Sting, and Kerr became pious embarrassments to American fans, Once, New Gold, and Sparkle became familiar thrift store trade ins, replaced by Nevermind, Odelay, and Ill Communication on our stereos. But Sons, Sister, and especially Empires remained in record collections, lingering for American younger siblings to discover along with Porcupine, Drums and Wires, and Doolittle. Across America, DJs might occasionally spin Dont You on classic rock stations, but indie alternative listeners ignore such broadcasts, resulting in SM’s most famous songs becoming essentially elevator muzak war horses for mallrat soccer moms to sing along to and embarrass their kids. SM are considered one hit wonders across this continent, a vague once vogue anachronism of an act.

Whereas that nifty blue banana graph mirrors the fertile crescent in a way that illuminates the invaluable long lost management of the early Minds Euro campaigns. Too bad a similar touring strategy wasnt developed in detail to conquer the States, because each region has its own unique cultural challenges. I suspect that SM would do well to cultivate their Catholic and Scottish heritage as they map out which cities in America to attempt future gigs. Delusions of grandeur might indulge arena shed booking, but by my estimation, there is only enough current interest for SM for concert halls, not stadiums, here in the States. Unless they opened for their super fan, Moby, and even then only venues in coastal metro areas.

Molly Ringwald’s current light jazz tour reveals the true nature of the post 85 SM fans; they are nostalgic for the John Hughes film and what it represents about their generation. Hughes catalogue of suburban malaise is revered by Americans of several subsequent generations too, resulting in some curiosity about the Iovine produced SM songs. That interest can be mistaken by SM as genuine, and maybe turned into cash, their newer gold dream, but it is not grounded in a real attachment to the band. It is not rooted in the first six albums, nor in the ones following Don’t You as a single. It is only a mirage, and will promptly vanish, even with the promise of another miracle, a new hit single.

So yes, SM might succeed with a limited American tour that harvests the Breakfast Club fans brief infatuation. But that illusion will disappear quickly, especially as middle aged American women do not attend large concerts unless at their State Fair. All SM will then be left with is the same lackluster few that currently attend Echo and Furs shows, a draw comparable to the one Big Country’s revival with Derek has.

And that is where the real work will finally begin; modest club gigs to win back hardcore old fans and new young critics. But sophisticates in my hometown here in Portland, Oregon already have Helio Sequence for their tech rock and the Dandy Warhols for their Bowie fix, two prolific active local bands who might have heard SM back in the day. Does SM really believe that crass bombs like Sanctify Yourself will work as well as I Travel on such young jaded hipsters? Apparently, but I beg to differ.

Smart Americans will instead crave the European urban travel writing in the early SM, even if don’t know it yet. Kerr is going to suffer greatly from cynical young smarty pants American criticism of any forthcoming arena money grab. Any remaining credibility will vanish unless they bring 5 X 5 to the States for a club/hall tour to compete with acts like the Kills and the Black Keys for true validity. Only by withholding the Forsey and Iovine SM material will the band ever become as respected in America as they want! Honest injun.

Everyone brings up U2 when trying to address this, but perhaps using Heart might make things clearer. This is what all Americans know already: early Heart rocks, even if that version of the band fell apart. And yes, mid period Heart had the largest hits, and biggest, most embarrassing hair videos too. But as Heart has reclaimed their position of relevance and credibility in recent years, they wisely abandoned their sell out hits (and terrible make up and hair) to play the old better stuff (and newer songs that sound like that). And they had the good taste to include the original founding members when inducted in the Hall of Fame, where they avoided their biggest awful hit songs, and instead properly played their rocking credible early songs. The Wilsons knew, deep down, that to do otherwise was to risk critical ridicule that could kill their comeback.

If only Jim and Charlie and Mel would realize this lesson! But instead, they show all signs of bringing the annoyingly awful Once Upon A Time version of themselves to America again to cash in. YUCK! They will get all that they deserve, and more, for such folly, because the youth of America are quick as always to point out that the emperor wears no clothes!

Spider Moccasin says:

Oct 11, 2013

What did I mean by the Emperor Wears No Clothes? That most of the current interest in SM from Breakfast Club fans is for a Keith Forsey lyric, not anything Jim Kerr wrote!

1. How do cities sustain creative milieux and cultural movements?

In the early eighties, Portland, Oregon had only one great new wave band with credibility, Theater Of Sheep (produced by Kurt Cobain’s hero, Greg Sage), and two new wave success stories; Quarterflash and Nu Shooz. As a western American city strong with rural culture, the new post modern MTV vocabulary of the Sheep, led by Jimi Haskett’s edgy guitar work, reflected new wave influences like Simple Minds, Echo and the Bunnymen, and Joy Division from across the pond. Portland’s perpetually rainy working class sympathized with Glasgow, Sheffeld, and Liverpool sound textures, and romanticized bleak UK post punk enough to spawn its own.

Whereas Portland’s Quarterflash was more of a sanitized version of Berlin, and Nu Shooz barely worth mentioning as a sub-Thompson Twins-like affair, Portland’s Theater Of Sheep were actually quite credible, both critically and to the old school punk acts they shared bills with, like Poison Idea. Raw Pacific NW punk rock that would laugh and blow pop like Quarterflash and Nu Shooz off the stage. Although it must be said that Oregon’s “finest,” Quarterflash, did hold its own, along with the Clash and U2, at the US Festival in this time period. If only SM had gone arena then, at that, instead of later!

The relationship and distance between critical merit (as demonstrated in Theater Of Sheep classics like “Annalisa”) and new wave imitation (Quarterflash’s “Harden My Heart” could just as easily be a Pat Benatar or Heart song with a sax solo added) was etched firmly in the Pacific NW culture that soon spawned Grunge. Later Portland, Oregon acts like the brilliant Sub Pop trio Pond shared the Sheep’s credibility with arena rock sized yet intimate alt. rock works of genius like The Practice Of Joy Before Death, totally avoiding selling out with hit singles.

Pond and Theater Of Sheep’s sharp, timeless music had much more to do with the early urbanism of Simple Minds masterpieces like Changeling and This Fear Of Gods, and less with later terrible SM hits like Alive And Kicking or All The Things She Said. Why? Pond and TOS avoided the prevalent pomp of these new romantics, yet still had all the muscle a Mel Gaynor could hope to pummel (Pond’s Dave Trebwasser being the best Pacific NW arena rock drummer short of Dave Grohl).

The groundwork laid by Portland acts imitating 80s UK new wave resulted in the current vogue celebrated by active Oregon exports like Dandy Warhols, Helio Sequence, and Sleater Kinney. But these bands do not sound anything like Once Upon A Time at all; instead they sound much more like Empires And Dance or Sons And Fascination. Which is to say, vivid and robust demonstrations of post-modern urban culture, instead of the noise of sold out has-beens cashing in on God or South African apartheid.

Why didn’t the Psychedelic Furs lose such credibility with their John Hughes film song? A close listen after their brush with brat pack infamy, Pretty In Pink, reveals that they did not sell-out. Book Of Days, the comparable post Hughes soundtrack release by the Furs, is a fine, if under-rated, disc full of authentic obscure non-hit songs, produced by a Cure board veteran in a murky, alt. style fit for the 90s, not the 80s. No loss of mojo there.

2. How are cities and the urban condition represented in art and popular culture?

Its been noted elsewhere that U2’s 90s albums are a lot like the early urban travel oriented Simple Minds music; Zooropa and Passengers being their Euro-centric Empires and Sons/Sister. One wonders if a desperate attempt was made to avoid those long held comparisons in the SM camp, resulting in tepid 90s releases ignored by us Americans. Here in the American Pacific NW, the survivors of the Seattle Grunge explosion faced the same dilemma, and found credibility by embracing shared styles and vocabularies instead of abandoning them; Pearl Jam didn’t ever try to stop sounding like themselves, and the Foo Fighters still don’t avoid being exactly what they are; a Nirvana spin-off.

But it seems to many Yanks that Simple Minds abandoned or lost their early sound and vision, replacing it with a hollow tin machine. Many of us blamed Jimmy Iovine, whose hit albums for Pretenders, U2, and Dire Straits were immediately followed by commercial and critical decline. As if working with the former Tom Petty Producer was the kiss of death for artists craving hit records, which he delivered as their peak period death knell, i.e. Get Close, and, ugh, Rattle and Hum.

Others blamed it on the shift in art direction made by Assorted Images’ Malcolm Garrett, whose impact on Simple Minds is comparable to that of Storm Thorgeson’s on the Pink Floyd. His heraldic imagery with crucifixes and such put off much of America’s mall-rat youth, who were initially attracted to SM’s exotic futuristic design aesthetic (as glamorous as their work for Duran Duran), but quite put off by an art shift towards pious Christian dogma. American children listen to rock music as an antidote to church, not to feel like they are in a cathedral, which is exactly what SM gradually evolved into sounding like to us. This is my old school U.S. Simple Minds Fan confession!

But I’m not even Catholic, and neither is most of the States. This is a Protestant nation mostly, and as such, holds the unique spiritualism found in Bono and Jim Kerr’s lyrics at arm’s length. Most of us groan and roll our eyes when “I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For” is played on the radio because of its ironic gospel evangelism, which is embarrassing and quaint to us, the remaining agnostic majority.

Skepticism of Catholicism in the United States is especially acute right now because of the molestation and sex abuse scandals. Instead of preaching to us about apartheid and Blood Diamonds in faraway South Africa, Kerr would have far more immediate impact addressing the current crisis in a church that is celebrated so in the most popular SM albums. Simple Minds will not find their new gold dream in North America with more than a John Hughes Memorial Run of arenas. But South America’s robust and enthusiastic mostly Catholic stadium audiences will make them very, very rich soon anyway.

Recent concert footage by Rush, the Police, and Iron Maiden show audiences in Rio love their old 80s melodies, jumping and dancing with wild abandon. Simple Minds are eager to tap that frenzy now. South American cities are full of modernized Catholic youth who are eager to participate in contemporary culture; but will they be fulfilled by SM’s new, hardly available music (that imitates their greatest period), or would those audiences prefer the older authentic vintage SM material that has been floating around record stores worldwide for decades? Yes, play the hits. But the rest of the sets should be 5 X 5!

3. What’s local (to a city, neighborhood, group) in any given art form or cultural movement?

Here in Portland, Oregon, super talented rock stars like the Pixies Frank Black and the Smiths’ Johnny Marr have recently found our NW atmosphere ripe for creativity. Marr’s work with Modest Mouse resulted in an American Number One on the Billboard charts. Too bad Kerr and Burchill’s collaborations with various production teams in faraway lands haven’t yielded the same great results. Portland is now a fertile epicenter of culture as the cultural zeitgeist hovers overhead, like our perpetual rain clouds and liberal dispositions, creating a perfect storm for our particular white hot day.

I suspect that the creative engine that was Derek Forbes, in conjunction with Mick MacNeil, was the actual hidden genius in what was the greatest period of Simple Minds, the band: albums two through six. SM’s nimble drummer Mel Gaynor was recently seen in promo footage describing the challenge of playing 5 X 5 sets last year, which contradicts the SM party line that Brian McGee wasn’t that great back in the day, and couldn’t cut it. But champions of late 70s-early 80s post punk like myself much rather liked the limitations of the art and prog rock rhythm playing of McGee.

Kerr insists that Gaynor is “…the best drummer in the world,” on my SM bootleg concert Self Luminous from Copenhagen ’84, while simultaneously and embarrassingly correcting poor Gaynor’s tempo and attack throughout the entire show! Were Copenhagen fans as disappointed as I was a year later in PDX to attend shows without much of any of the early urban and travel material we previously loved Simple Minds for? Or was their attachment to prior works as fleeting as mine halfway around the globe?

I used to enjoy The American (SM’s first notable song to totally alienate many Yank fans by insulting our very nationality), but have grown to hate its inclusion as an odd number from a favorite early album still on set lists and compilations, along with Love Song. Simple Minds continue to play The American on tour, and audiences still joyously sing along with the sarcastic and ironic hook. But is it any wonder that the song eliminated potential American buyers by the thousands, and continues to do so every time it’s played?

What are American DJs, booking agents and promoters to make of the message in all of that? Frankly, the song comes across as a smug and snotty anti-American rant to most Yanks, who are dismayed by such pompous Europeans failing to recall with gratitude and respect America’s role in saving them from the Nazis in World War Two. It isn’t lost on Americans that Simple Minds early works also imitate krautrock, which sometimes echoed post fascist ranting to casual listeners in the States.

But that really isn’t what burned us American old fans to the band. Instead, it was the Simple Minds Bait and Switch that alienated us: We spent our hard earned teenage dollars slowly collecting Reel To Reel Cacophony and fell in love with Premonition. We worked minimum wage jobs at our malls to score Empires And Dance to play Constantinople Line over and over again. And we saved up and bought Celebration, even though we already had most of the tracks.

We worshipped at the altar of Sons And Fascination, driving everywhere with it on our car stereos. We adored Sister Feelings Call as we roamed from Seattle to Portland on Interstate Five in the wind and the rain. We dealt with the crucifix on New Gold Dream by focusing on Somewhere, Someone, In Summertime’s optimism, and ignoring the way Promised You a Miracle sounded like Tears For Fears or ABC’s new romanticism.

We toasted the marriage of Kerr to the Pretenders’ Chrissie Hynde as if he was becoming ours now too. And we delighted in the bombast of Sparkle In the Rain as our motor scooters sped our love elsewhere. But A Brass Band In Africa, the ethereal b-side to the Don’t You Forget About Me 45 RPM single, had more integrity than its flip twin by Keith Forsey to us. And when it dropped, out the window went our interest in SM.

When combined with the firing of Forbes, and the eventual defection of MacNeil, that Breakfast Club single utterly killed old American fan loyalty. By the time SM toured Once Upon A Time without playing much early work, we were lost to the band. Not even Police drummer extraordinaire Stewart Copeland lured us back after the Paris live LP.

Where were all the old SM songs we so loved? Gone, apparently for good, until the 5 X 5 Tour. With that, disenchanted old American fans were reawakened after a quarter century as word from afar filled us with hope for those rarities, to be played again live at last. But why didn’t we see SM do those songs when they first toured the States?

Most of us were not old enough to even go into nightclubs way back then! So we have always craved that set, especially from long lost Brian, Derek, and Michael. But Kerr seems more interested in plugging his expensive, elitist vacation hotel in Sicily than ever satisfying us, his old fan-base in the colonies. We seem to represent the dead past to him.

Can the struggling youth of Glasgow, Johannesburg, Berlin, or my Portland home really relate to the pleasures of Kerr’s expensive hideaway for the super-rich? Does his hotel clientele respect him for all of his lyrics, or just one of Keith Forsey’s? Kerr relaxes in such posh splendor, but his poor old loyal fans have to judge his holier-than-thou human rights messages with some skepticism when delivered from such a lifestyle of luxury and privilege. Talk about preaching from an ivory tower!

Speaking Truth To Power requires a kind of integrity and humility that superstars like Tantric sex braggart Sting, Saint Bono of the Blues, and Simple Minds’ singer Jim “Sanctify Yourself- be a part of ME” Kerr just no longer seem to possess after jumping their respective career sharks. But they were my heroes indeed, Once Upon A Time.

Simple Minds have replaced gold with diamonds, and by doing more of their Street Fighting Years era human rights activism, are still quite desperate to link the struggle against apartheid in South Africa with themselves. Their upcoming gigs there may be validated by SM’s history with Nelson Mandela, even as they violate the spirit of the old U.N. cultural boycott. But in a different way than Paul Simon’s Graceland, instead bearing similarities to the obscure folk artist Rodriguez’s triumphant pilgrimage, captured so poignantly in the recent moving documentary, Searching For Sugar Man.

However in that film, there are few blacks celebrating Sisko’s arrival. This is because those albums were appreciated most by guilty white Afrikaners instead, as was the case with Simon’s hit song Diamonds On The Soles Of Her Shoes. It will be interesting to see if very many black South Africans relate to Simple Minds brand of social justice either with their new single Blood Diamonds, or if their tour and new single are just more profitable symptoms of guilt for genocide and slavery, played for mostly white audiences.

Stretch. says:

Feb 13, 2014

Under “New Gold Dream & Sparkle in the Rain” – Book of Brilliant *Things*.

Thanks for a fascinating analysis, I really enjoyed reading it.

dark indie music says:

Oct 21, 2014

thanks for the entertainment

flerp says:

Jan 16, 2016

Outstanding. And very much needed, I really felt this urban imagery in SM work, E&D and S&F/SFC being the peak of the whole thing (in terms of musical achievement, too).

The NGD/SITR turn is so well depicted. Completely missed that rationally… it is the same concept of the live album In The City Of Lights, really.

The tour stats and the blue banana and the southern sunny heavens… so much fun.

Bro you are a pro!

Stuart Holland says:

Mar 26, 2018

Just enough the music