It’s been said 14 is the influential age in the development of our musical tastes. That was the case for me: I find I regularly return to the music that I explored and embraced as my own back around 1983. It wasn’t just what I heard that has shaped my ideas about ‘good’ music, though, but how and where I heard it.

Suburban lessons in DC hardcore

When I was 14 years old, I was a freshman at McLean High School in McLean, Virginia, a suburb of Washington, D.C. At the time, McLean was well-to-do but not yet submerged into the extended Northern Virginia sprawl that now characterizes the Washington metropolitan area. For instance, the town’s major shopping mall, Tyson’s Corner, didn’t yet have the retail/office expansion for which journalist Joel Garreau would deem it the ur-Edge City. A number of our parents worked “inside the Beltway” at government jobs, but otherwise high school kids lived lives roughly familiar to the teenage life depicted in “Dazed and Confused”: jocks and preppies, long-hairs smoking cigarettes in the parking lot (“fleabags,” we called this group), and the unquestioned hegemony of rock radio from stations like WAVA and DC-101.

Something musically exciting was happening in the city, but as a freshman too young for a driver’s license, I could only get glimpses of it. Legendary alternative-radio station WHFS broadcasted with a weak signal back then that I couldn’t really tune into from where I lived. Family excursions into the Georgetown neighborhood (the most visible scene for DC’s first wave of gentrification) were infrequent, but a couple of trips to the new wave boutique Commander Salamander there were tremendously exciting for me. And most famously, hardcore punk was raging in DC in 1983, maybe the last year in its golden age marked by the career of Minor Threat.

My musical tastes were already evolving to reflect British new wave and postpunk in my freshman year. I was really affected by acquiring and, separately, going into record stores to buy albums like the Clash’s Combat Rock, the Psychedelic Furs’ Forever Now, ABC’s Lexicon of Love, the Human League’s Dare (actually, that was taped off a full-album broadcast on FM radio), Devo’s Oh No It’s Devo, and Duran Duran’s Rio. (The influence of the suits that Duran Duran wore on the back cover of Rio is the subject of another blog some day.) But DC hardcore was in the ether at my high school back then, if you knew where to look, or who to look at.

The guys who played in the high school’s unofficial ultimate frisbee team (the Flipping Lids) looked not too dissimilar from the fleabags — shaggy hair, flannel shirts, the scent of some kind of smoke wafting from their cars. But then I saw a few of them play a mangy version of “Louie Louie” at a high school talent show with an alternate lyric: “Who needs love when you’ve got a gun/Who needs love to have any fun.” I soon learned they played Black Flag’s version of “Louie Louie.” Or then there were the kids involved in theater — the “drama queers”, they were called — that I ran with thanks to working on the tech crew for “Fiddler on the Roof.” From them I discovered Fear’s debut album The Record and danced (if that’s what you called my G-rated spazzout) to “Beef Baloney” at a theater party.

Yet I really have Nils Ahlgren to blame/thank for showing me the world of DC hardcore. Nils was a problem child, if I recall correctly: smart but disruptive in class, verbally dismissive of the popular kids, a little uncomfortable-looking in his nondescript clothes. I don’t recall how we latched on to each other freshman year, but he found a willing and impressionable comrade in me. He came over to my house one day with three LPs that showed me a new world of sound and style: the Ramones’ Subterranean Jungle, Public Image Limited’s Flowers of Romance and the Alternative Tentacles compilation of North American hardcore Let Them Eat Jellybeans. In Spanish class, we would go to the library’s language lab, where he would eject the Spanish exercise cassette and pop in homemade tapes of DC music that he had collected, such as hardcore heroes Government Issue or local weirdoes 9353. (This is how we shared music in the pre-Internet age, kids.)

The go-to tape in these sessions was the Dead Kennedys. For a nice kid like me, there was nothing as illicit, profane and chilling as listening on cheap language-lab headphones to Jello Biafra incant the opening line of “I Kill Children”: GOD TOLD ME TO SKIN YOU ALIVE… I was suitably freaked out, but I didn’t protest, and so we listened again and again to the San Francisco band’s early recordings: the debut Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables, the “In God We Trust” EP, and their last essential record Plastic Surgery Disasters. Toward the end of school year, Nils had a proposition: let’s go see the Dead Kennedys in concert.

I like to think of this event as my first concert, no doubt because it makes a great story: “My first show was the Dead Kennedys, 1983, in Washington DC — beat that!” Technically, my first concert was the summer before: a free Beach Boys concert at the National Mall that drew hundreds of thousands of people (including my sister, her friends and me) to lay a blanket out in front of the Washington Monument, play some frisbee, take shelter under tarps from an afternoon downpour, and then hear a Brian Wilson-less Beach Boys play their feel-good classics… Come to think of it, maybe I should restore this concert to its proper place in my musical autobiography, since it was after this event that then-Secretary of the Interior James Watt notoriously complained that the Beach Boys attracted “the wrong element” and brought in Las Vegas crooner Wayne Newton to headline the free concert the following year.

But no matter — back to the Dead Kennedys concert. This would be my first real “show”: at night (i.e., rock’n’roll time!), in a real venue, paying money. Instinctively, I was afraid to accept Nils’ invitation, so intense, speedy and oppositional was the DKs’ music. But he offered to go get the tickets and take care of the transportation. Having alrady established a tradition of being easily swept up into Nils’ plans, I told him I’d ask my parents.

In retrospect I’m surprised they agreed, since just within the year they cut short a weekend in New York City because my mother was held up in a garment-store armed robbery. Her fear of urban environments was visceral back then, although truth be told my parents were never intrepid urban explorers. My knowledge of Washington the city was limited to the areas they took me to: the government/monument/museum zone around the National Mall, an occasional Georgetown outing, once to see the pandas at the National Zoo, and a few bike rides along the C&O Canal. My taste for urban adventure in those years instead materialized around weekend journeys on the public bus to a comics store at Arlington’s Crystal City underground shopping center — in a gleaming high-rise urban setting along the Potomac River, but still not DC proper. I suspect my parents said yes because these solo expeditions gave them some faith in my trustworthiness, and because afterward I would be staying at Nils’ house. They might have also let me go because my father had recently dropped a bombshell: a U.S. Army doctor working at the Pentagon, he was being transferred to Belgium, so we would be leaving the country in a month’s time. My sister and I were still in shock about that.

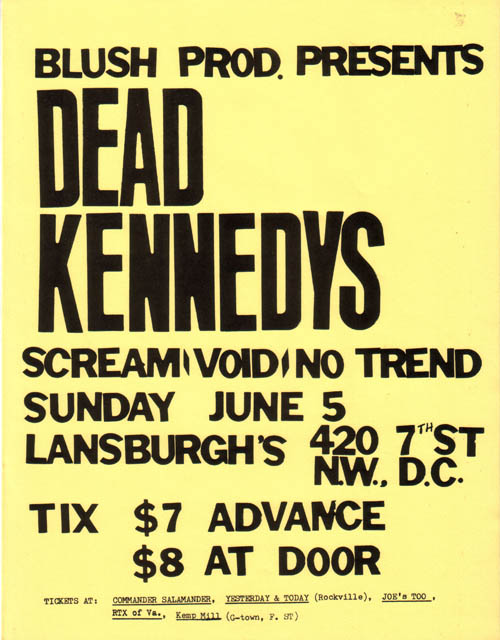

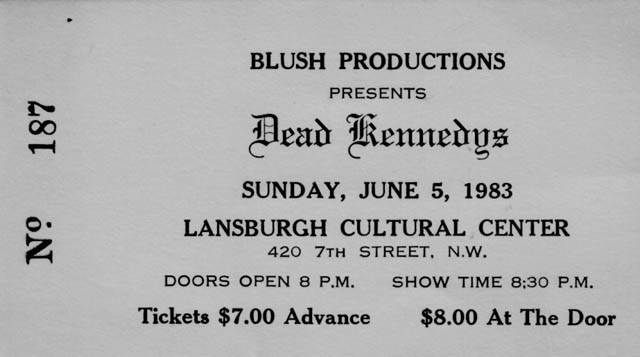

Concert day: Sunday, June 5, 1983

My parents dropped me off at Nils’ house, and he and I spent some time listening to his small but impressively indie record collection. I wish I remembered what I wore that day: I had no punk clothing to speak of, but I either had the good sense or Nils’ advice not to “be a poseur” and fake a punk look. Then Nils’ mother came home. I had been alerted already to the fact that Nils didn’t have a warm relationship with his mom — a divorcée in her late 30s who looked like she had an office job and had her hands full raising a sullen teenage boy by herself — but the maternal nagging and filial resentment began in earnest after I introduced myself to her. There was a knock at the door: her boyfriend, a 40-something man with glasses, a trim beard, short-sleeved office shirt and tie.

We got into his car and headed out, where Nils’ mother announced the itinerary: they would drop us off at the concert, enjoy a weekend evening out in the city, then pick us up at 11:00, when the concert was scheduled to end. I don’t know where she got that last fact. Not having been to a nighttime concert before, I didn’t question these plans aloud, but still I wondered whether 11 o’clock might be too early, and exactly how Nils’ mother would find us.

We drove for a good while, taking shortcuts and surface roads here and there, until we were thoroughly off my mental map of Washington DC. Our destination was evidently in the N.W. quarter, the same area with most of the museums and government buildings I had visited, but I didn’t see any tourist attractions around me. We had driven into generic “downtown DC”, a functioning yet drab and (to my suburban sensibility) vaguely menacing commercial district. A line of kids wrapped around the block lay ahead, and we pulled over. This was our destination: Lansburgh’s, a.k.a., the Lansburgh Cultural Center, a venue that I had never seen mentioned previously in all the times I glanced through the Washington Post’s entertainment section, making mental note of concerts I wanted to attend but never would. “We’ll see you at 11:00 — wait for us outside,” Nils’ mother told us, and they were off.

I was agog at the line of humanity before me: teenagers and 20-somethings, short-cropped hair with more coiffured haircuts here and there, t-shirts graffitied with DIY band logos and scene slogans (“Boycott Stabb,” etc.). Maybe I was waiting for violence to erupt, but I soon became aware how everyone was well-ordered. We got in line, and Nils started a conversation with the girl in front of us; she had a painfully short haircut, a Minor Threat “Out of Step” t-shirt, and big Xs felt-tipped on the back of her hands. Elsewhere in the line, a guy in a Void t-shirt who didn’t seem so tough-looking to me was being interviewed; he mentioned something about antagonism between local punks and heavy metal kids. Hey, was that one of the ultimate frisbee guys from McLean High School? Finally, the line started moving, and we entered the Lansburgh Cultural Center.

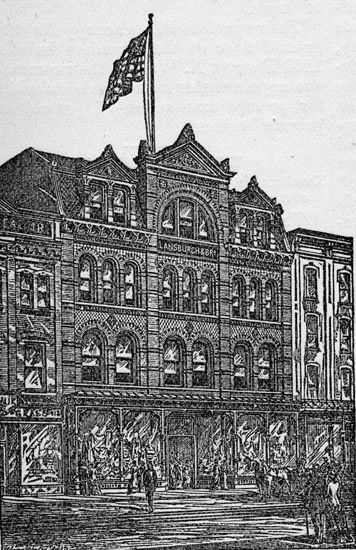

Lansburgh’s

The venue had seen better times. For old-time Washington residents, “Lansbugh’s” would have signified the defunct D.C.-based department store chain; this building was its flagship store. Adolph Cluss, a German architect and personal friend of Karl Marx, built the original store here (with D.C.’s first commercial elevator) in 1882. Through subsequent expansions, Lansburgh’s grew to a six-story department store that was in business for almost a century. In 1973, the urban crisis and (later, after the chain opened stores in Tyson’s Corner and other suburban malls) retail restructuring put Lansburgh’s out of business.

The solid, impressive building was later adapted to office use, warehouse storage, and — by the time of the Dead Kennedys show — a “cultural center” for local arts and organizations well below the radar of the city’s arts and culture establishment. By 1983, DC’s enterprising punks recognized the building’s value as a concert venue. Steve Blush, a George Washington University student and later author of American Hardcore, booked the Dead Kennedys for this date, a year after he organized their well-attended gig (his first promotion) at GWU. He would organize a couple more shows at Lansburgh’s over 1983-4, including a remarkable “DC Funk-Punk Show” in which Trouble Funk headlined over Minor Threat and (from Austin) the Big Boys.

I knew none of this history at the time, but as the kids filed into the venue, I soon figured out that the building was once a department store. Glass doors opened onto a spacious ground floor with a high ceiling and, at the center, a second-story mezzanine that provided a balcony view to the stage below. They no longer built department stores like this in Tyson’s Corner or other malls, but I recognized a similar layout from the Holman’s Department Store in Pacific Grove, California, where I lived in my grade-school days. (Yes, I moved a lot as an army brat.) A little daunted by the general admission crowd on the ground floor, Nils and I went upstairs to the mezzanine where we sat for the rest of the evening.

The show

Adrenaline was flowing as the first band hit the stage. Oh god, I’m about to experience a hardcore concert! But it was No Trend, a group of arty looking skinheads playing their signature slow, buzzkill punk rock. I made a mental note that they sounded like Flipper, whose “Ha Ha Ha” was one of my favorite songs on the Let Them Eat Jellybeans compilation (and way more interesting than No Trend), and then sat down through their seemingly interminable set. It will get better than this, I hoped.

And it did! Void took the stage: four guys looking strangely suburban, their dude-looking singer wearing an Izod polo shirt (collar flipped up, natch) and Birdwell beach britches. And they RAGED!! So fast, so loud, so young — why, they were just like me! One song — over! Second song, third song, fourth song — oh please, let this never stop!!

Then, suddenly, it stopped. The band looked offstage, confused, and eventually filed off the stage. That’s when the kids REALLY erupted.

This story, it turns out, has been documented by Mark Andersen and Mark Jenkins in Dance of Days: Two Decades of Punk in the Nation’s Capital (Soft Skull, 2001), so I’m going to let them explain what happened.

Another new venue was the Lansburgh Cultural Center, a former department store in downtown Washington that was owned by the city government and subsequently redeveloped as an apartment building. When Dead Kennedys, Scream, Void, and No Trend played there, more than 1000 people turned out despite what was then a high ticket price: eight dollars.

Observing was Charles M. Young, who was researching a Playboy article on hardcore. He watched as DC fire inspector T.R. Gardner tried to shut down the show during Void’s set, accusing promoter Steve Blush of not having the right permits. Blush went onstage to tell the crowd that the concert was over; the crowd began to boo angrily and then spontaneously sat down on the floor and started chanting, demanding a show or a refund. The fire marshal refused to back down, instead calling the police. As the crowd began to sing songs like “I’ve Been Working on the Railroad” and “God Bless America,” the Dead Kennedys’ Jello Biafra was asked to try to convince the audience to end its sit-down strike.

Outside, there was a line of police cars and some arrest vans and ambulances; inside, [Minor Threat’s Ian] MacKaye warned Biafra not to jeopardize punk-police relations, which weren’t nearly so adversarial in Washington as in California. Biafra later recounted being “caught between a rock and a hard place, DC cops on one side and Ian on the other, saying, ‘Don’t you dare cause a riot in my town, don’t you dare fuck up my town!”

Returning to the stage, Biafra encouraged the fans to continue their nonviolent sit-down, while entertaining them with a capella versions of Dead Kenedys’ songs — including “Let’s Lynch the Landlord,” which to some in the crowd became “Let’s Lynch the Fire Marshal” — as negotiations continued.

“The DC punks seem to instinctively know to sit on the floor and save the threat of violence for a last resort,” Young wrote in Playboy. “They are, nonetheless, very close to the last resort. The faces of the dozen or so cops [inside the hall] change from horrified fascination with the female punk aesthetic to barely concealed fear that their precinct is about to be trashed. Gardner locks himself in a side room. ‘This is a test,’ Biafra tells the crowd between blasts of feedback from a bass amp the band had managed to get working. ‘We can’t lose our tempers or they’ll make it impossible for us at other shows.'” (pp. 142-3)

Throughout all this, Nils and I were glued to our seats as the protest unfolded over what seemed like an hour or two. Agitated cops and firemen barked demands to some guys (Steve Blush?) who were probably only 5 years older than us but seemed seemed like elder statesmen, so competently and fearlessly did they stand up to the authorities. We sang along with the crowd’s chants — “HELL NO, WE WON’T GO” — although no way were we going to move downstairs to center of the protest. Jello Biafra’s statements to the kids were simultaneously assuring and coded with dissent, as sarcasm dripped from his so-called plea: “Now, we don’t want to cause any trouble…” Like most people in attendance, I was itching for the show to resume, but gripped by the potentially explosive scene unfolding before us.

Then a suburban-looking woman in her late 30s waded through the floor of seated punks to just below our mezzanine perch and shouted repeatedly:

“NILS!!! GET DOWN HERE!!! NILS!!! GET DOWN HERE!!!”

It was Nils’ mom. It was 11 pm.

Nils and I looked at each other. “NILS!!! NILS!!!” His face red with embarrassment, Nils instantly rechanneled his contribution to the on-going protest toward anger at his mother. But he got up nonetheless, and I followed him downstairs as we walked through the crowd toward the exit. (Sadly, it’s difficult to lose your mother in a sit-down protest.) As we got into her boyfriend’s car outside, we saw police paddy wagons and fire engines circling the building. Nils was about to protest, but his mother was having none of it:

“WHAT WERE YOU DOING IN A PLACE LIKE THAT? DID YOU SEE THOSE PEOPLE? YOU COULD HAVE BEEN ARRESTED AND THROWN IN JAIL! WHEN WE GET HOME, I WANT YOU TO THROW OUT THOSE PUNK RECORDS! NO MORE OF THEM, DO YOU HEAR ME?”

This tirade continued all the way home, his mom adding a few remarks for my benefit: “LEN! WHAT WOULD I TELL YOUR PARENTS IF YOU WERE ARRESTED?” We had no smart or witty retorts for her as we eventually got to Nils’ house. His mother gave an almost tearful, oh-what-we’ve-been-through embrace to her boyfriend as he left, while Nils and I skulked into his room. I felt bad for Nils, who was looking at the loss of his beloved punk records and sinking into deeper resentment of a mother who couldn’t understand how righteous this whole scene was. But I also realized something that night: this punk thing is alright with me.

Also, I comforted myself with the fact that at least I didn’t miss anything, because the show wouldn’t go on that night… Except, as I learned from one of my drama queer friends the next day, that it did! What happened? Once again, Andersen and Jenkins:

The building manager announced that a compromise was possible. Young detailed: “The crowd cheers and Biafra takes the mic back to lead them in another rousing a capella until negotiations are complete. ‘If you’ve come to fight, get out of there,’ 1000 punks sing as one. ‘You ain’t no better than the bouncers/We ain’t trying to be police/When you ape the cops, it ain’t anarchy/Nazi punks/Nazi punks/Nazi punks — fuck off!'” Ultimately the Dead Kennedys were allowed to play for 40 minutes. Disaster had been averted by flexible, united action, a testament to the power punks could wield if they agreed on an objective (pg. 143).

So I never got to see the Dead Kennedys perform, but the damage was done: punk changed my life that night. Yet I lost complete touch with Nils Ahlgren once the school year ended, and I never got the chance to dive further into the DC hardcore scene. In July, my family boarded an airplane for Belgium, where there was no hardcore scene to speak of. Instead I read the NME and the Face religiously for two years, becoming socialized into a British music snob’s sensibility about punk (it was dead, year zero being 1977), postpunk (it was the now), and American roots rock (it was exotic). I actually found my copy of Minor Threat’s Out of Step at a record store in Brussels, along with other American imports like R.E.M.’s Murmur. With no scene to explain in those formative years the very different meanings of these two U.S. “underground” records, my approach to punk has since been very catholic. Punk is about doing, not passively consuming, and furthermore about doing what you want, parents or peers be damned. Seen that way, punk can cover just about everything, from thrash metal to noise music to a way of life — which, these days, is another way that punk can mean nothing at all.

Postscript

Today, the old Lansburgh’s building has been redeveloped almost beyond recognition. The Lansburgh houses the Harman Arts Center and, above that, high-end condominium apartments. Its once-nameless stretch of “downtown” NW has been gentrified and rechristened Penn Quarter.

[Research on this essay was greatly assisted by Johanna Bockman, a colleague and blogger on Sociology in my Neighborhood: DC Ward Six, and DC-based music writer Steve Kiviat. Thanks, you two.]

5 comments

Russ Morin says:

Mar 20, 2015

I was there too, Leonard. I went with an older buddy of mine who could drive. We were up in the mezzanine so we were removed a bit from the intense tension on the ground. We stayed and got to see an amazingly energetic set by the DKs. I remember that once the music started, the crowd surged toward the stage (basically a removable riser), pushing the whole thing back against the wall. If anyone had been standing between the stage and the wall would have been crushed.

Thanks for the memories.

Russ

Barry says:

Dec 12, 2015

I was there too! Maybe my memory is off but I remember the dk set being a lot shorter thank 40 minutes. More like 15 minutes. But they crammed in about 20 songs! Some they would do a verse a chorus then stop and launch into another song. The place just went mental, knowing we had such a short amount of time.. One of the funnest shows I was ever at. Everyone left, drenched in sweat and laughing.

michael salkind says:

Nov 27, 2016

I was there as well, drumming for No Trend.

Matt says:

Jan 10, 2018

Nicely done, Leapin’ Lenny Nunchucks!!

Leonard Nevarez says:

Jan 10, 2018

Who is this, who dares to call me by my junior high superhero alias?