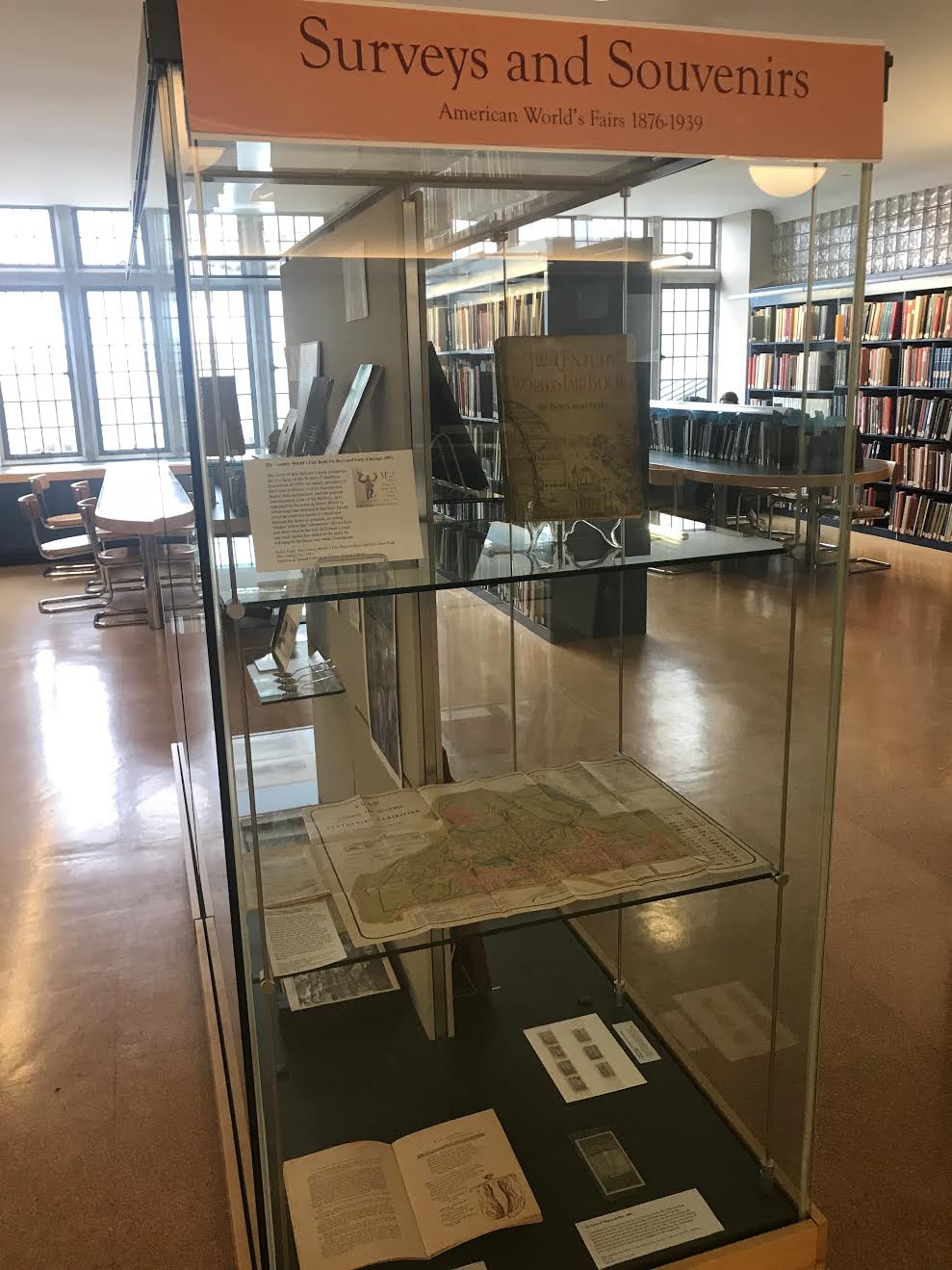

An Exhibition in the Vassar College Art Library March 12-May 29, 2018.

This exhibition was curated by Emily S. Warner, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Art, with the assistance of students in her Art 385 seminar: “Visual and Material Culture of U.S. World’s Fairs,” Vassar College, Fall 2017.

“Sell the cookstove if necessary,” novelist Hamlin Garland wrote to his parents in 1893; “You must see the fair.” Garland’s comment captures the excitement and urgency that drew 27 million visitors to the World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago, one of several world’s fairs that dominated American cultural life around the turn of the century. From 1876 to 1039, over 15 world’s fairs opened in American cities, showcasing the nation’s industry and art, and introducing Americans to a world of foreign goods and accomplishments. Drawn chiefly from materials in the Archives and Special Collections Library at Vassar College, this exhibition presents the rich material culture of American world’s fairs, from surveys and guidebooks to photographs, children’s literature, poster stamps, and souvenirs. Many of these objects tell official stories from the fairs, promoting messages of American progress, imperial expansion, or scientific advancement. They also tell more personal stories, as material objects that were used, gifted, inscribed, and collected. Together, they paint a vivid picture of American world’s fairs during a time of intense national growth and consolidation, as the country celebrated its centennial, closed its Western frontier, and arrived at the eve of World War II.

Please note: A recording of a radio interview about the exhibit conducted by Thomas Hill with curator and art historian Emily S. Warner, along with links to documentary videos about these Fairs on Youtube, can be accessed at this link.

A SELECTION OF ITEMS ON DISPLAY

Guide and map, Centennial Exhibition (Philadelphia, 1876)

The Centennial International Exhibition in Philadelphia represents an important

shift in fair design: unlike the single-pavilion fairs at the London Crystal Palace

(1851) or the Exposition Universelle in Paris (1867), the Centennial included

hundreds of pavilions set into a large tract of parkland. Removed from downtown,

the picturesque site necessitated new transit links with the city: note the specially

built railroad depots near the main entrance (bottom center) and the Lansdowne

Drive entrances (top right). A short monorail (175-A on the map) and the much

longer West End Railway provided transportation inside the fair.

Visitors Guide to the Centennial Exhibition and Philadelphia. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1876. Archives & Special Collections Library, Vassar College

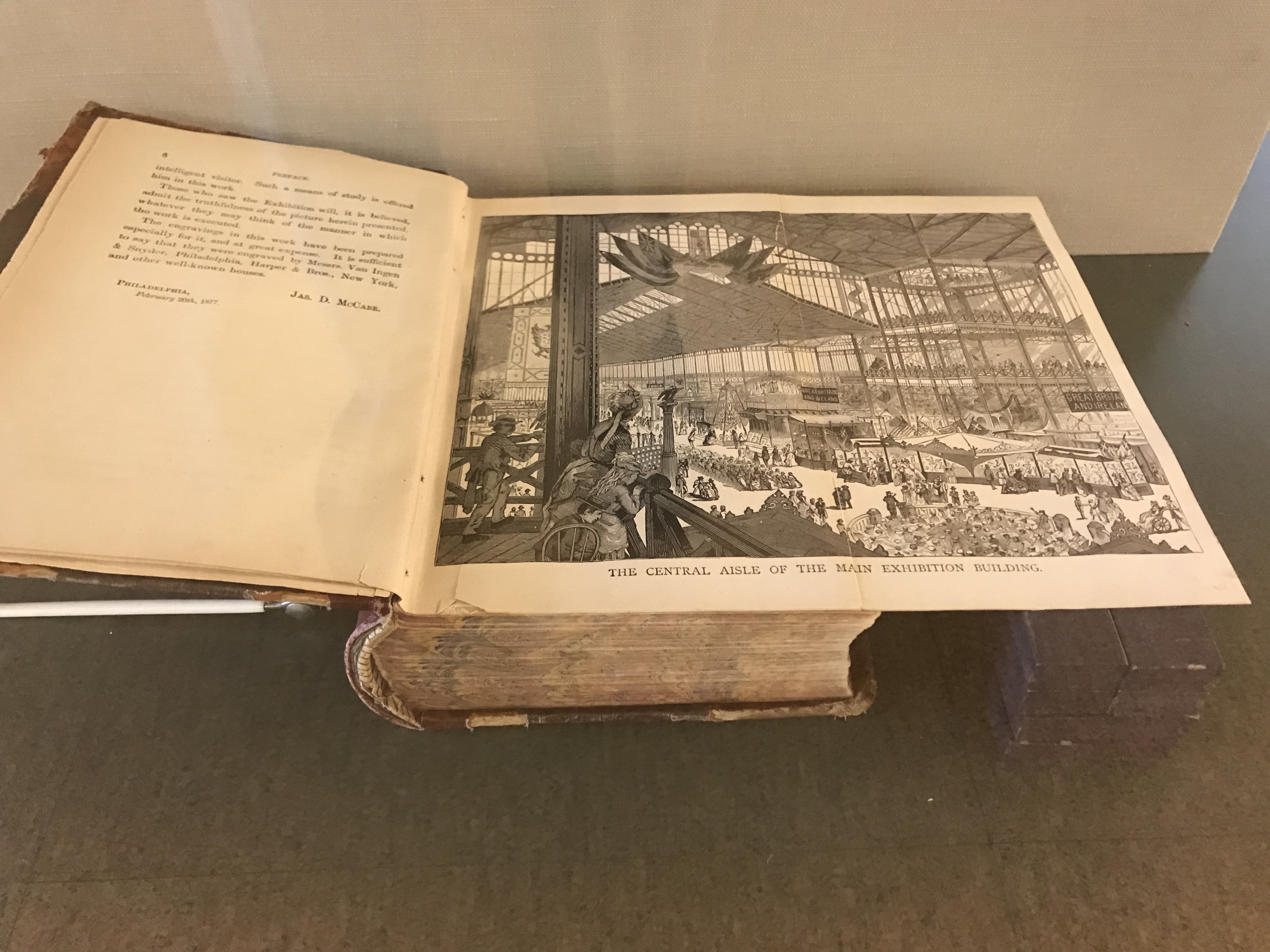

The Main exhibition at the Centennial (Philadelphia, 1876)

The staggering array of objects brought together by world’s fairs is apparent in this

engraving of the Main Building at Philadelphia’s Centennial Exhibition. In

addition to their explicit national themes, nineteenth-century expositions were

epistemological projects, attempts to order and understand the expanding world of

knowledge. Here, as at other fairs, the ideal building type for such a project was

derived from engineering: the Centennial’s Main Building was essentially a series

of parallel railroad sheds, crossed by three transepts, which allowed for

inexpensive construction and the long vistas seen in the illustration. The Main

Building is also visible as the largest structure on the color map at right.

“The Central Aisle of the Main Exhibition Building.” In James D. McCabe, The Illustrated History of the Centennial Exhibition, Held in Commemoration of the One Hundredth Anniversary of American Independence. Philadelphia: The National Publishing Co., 1877

Vassar College Libraries

The cover of this children’s book juxtaposes the two faces of the World’s Columbian

Exposition of 1893: the stately grandeur of the Court of Honor, with its lagoons and

Beaux-Arts architecture, and the popular entertainment zone of the Midway, here

indicated by the rotating Ferris Wheel (a technology that debuted at the fair). Inside,

vivid descriptions enable a virtual tour through the faraway grounds, as young

readers follow the “adventures” of two boys and their tutor at the fair. In Vassar’s copy, one such reader has added to the story by coloring in the black and white illustrations.

Tudor Jenks. The Century World’s Fair Book for Boys and Girls. New York:

The Century Co., 1893. Archives & Special Collections Library, Vassar College

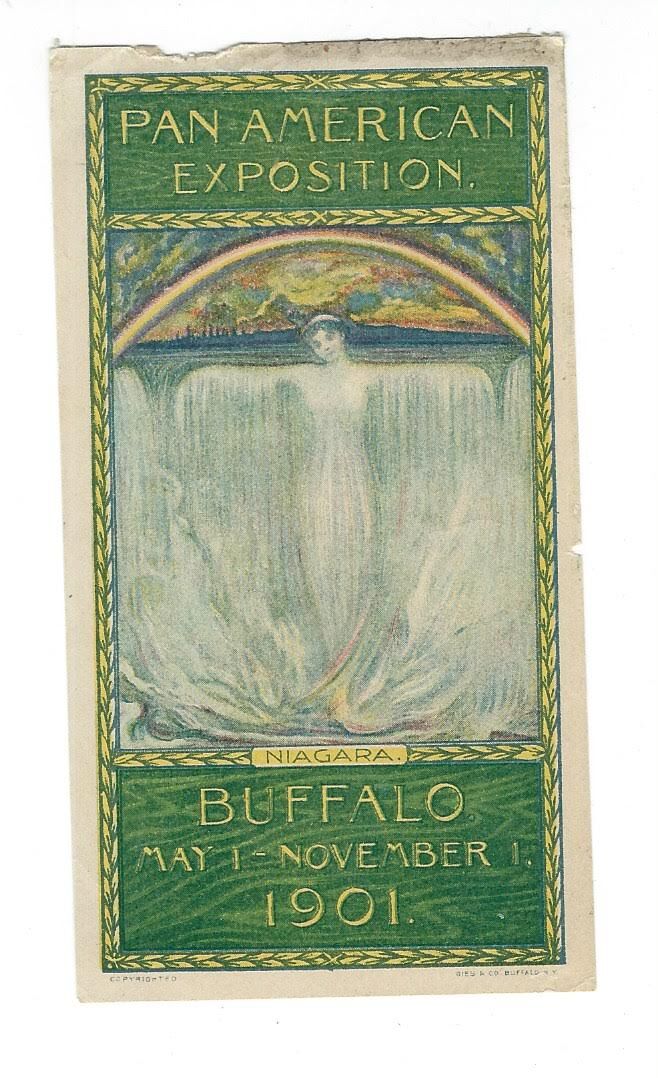

The Spirit of Niagara (Buffalo, 1901)

The Spirit of Niagara (Buffalo, 1901)

Evelyn Rumsey Cary painted The Spirit of Niagara for the 1901 Pan-American

Exposition in Buffalo, and it soon became the unofficial image of the fair,

reproduced in newspapers, books, and guides. In Cary’s Art Nouveau design, the

spirit of the waterfalls emerges from the mist, emblematizing not only their natural

beauty but also their tremendous electrical power. By 1901, Niagara was an icon of

industry and progress, and visitors marveled at the technology that transmitted

power from the falls to the Electricity Building on the fairgrounds.

“Pan American Exposition.” Evelyn Rumsey Cary, designer. Printed by Gies & Co., Buffalo, NY. 1901. Collection Arthur H. Groten

Flashes from the Pan (Buffalo, 1901

This illustrated book sets the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo to music.

Characters such as Uncle Sam, the Maid of the Mist, and the “Man-with- Camera”

sing about the fair’s more spectacular displays, including the Johnstown Flood and

the infamous living exhibits of foreigners and Native Americans.

Prescott Bailey Bull. Flashes from the Pan: A Fantasia in Retrospectio and Imaginatio. Drawings by Eleanor Withey Willard. Grand Rapids, MI: Michigan Trust Co., 1901. Archives & Special Collections Library, Vassar College

Bartelda, Apache (Omaha, 1899)

Bartelda, Apache (Omaha, 1899)

Photographer Frank Rinehart produced a remarkable series of images of Native

Americans at the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition of 1898-99,

which hosted the largest Indian Congress yet convened at a world’s fair. In this

photograph, Rinehart uses tonal contrasts—dark hair, the black line along the lapel,

and the subtler grays on the face and coat—to create a sensitive depiction of a

young man at the Congress named Bartelda. His gaze, directed out of the frame,

and his somewhat inscrutable expression endow the image with a rich

psychological dimension. Yet in other ways, the photograph reduces Bartelda to a

type, his profile exposed for maximum legibility and his tribal affiliation written

across the bottom. One of many professional photographers who photographed

ethnic and racial “others” at American world’s fairs, Rinehart here offers us an

image somewhere between individual portrait and ethnographic type.

Frank A. Rinehart (American, 1861-1928). Bartelda, Apache, No. 1386, 1899.

Platinum print. Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center. Purchase, Anne Hoene Hoy,

class of 1963, Fund, 2017.22.3

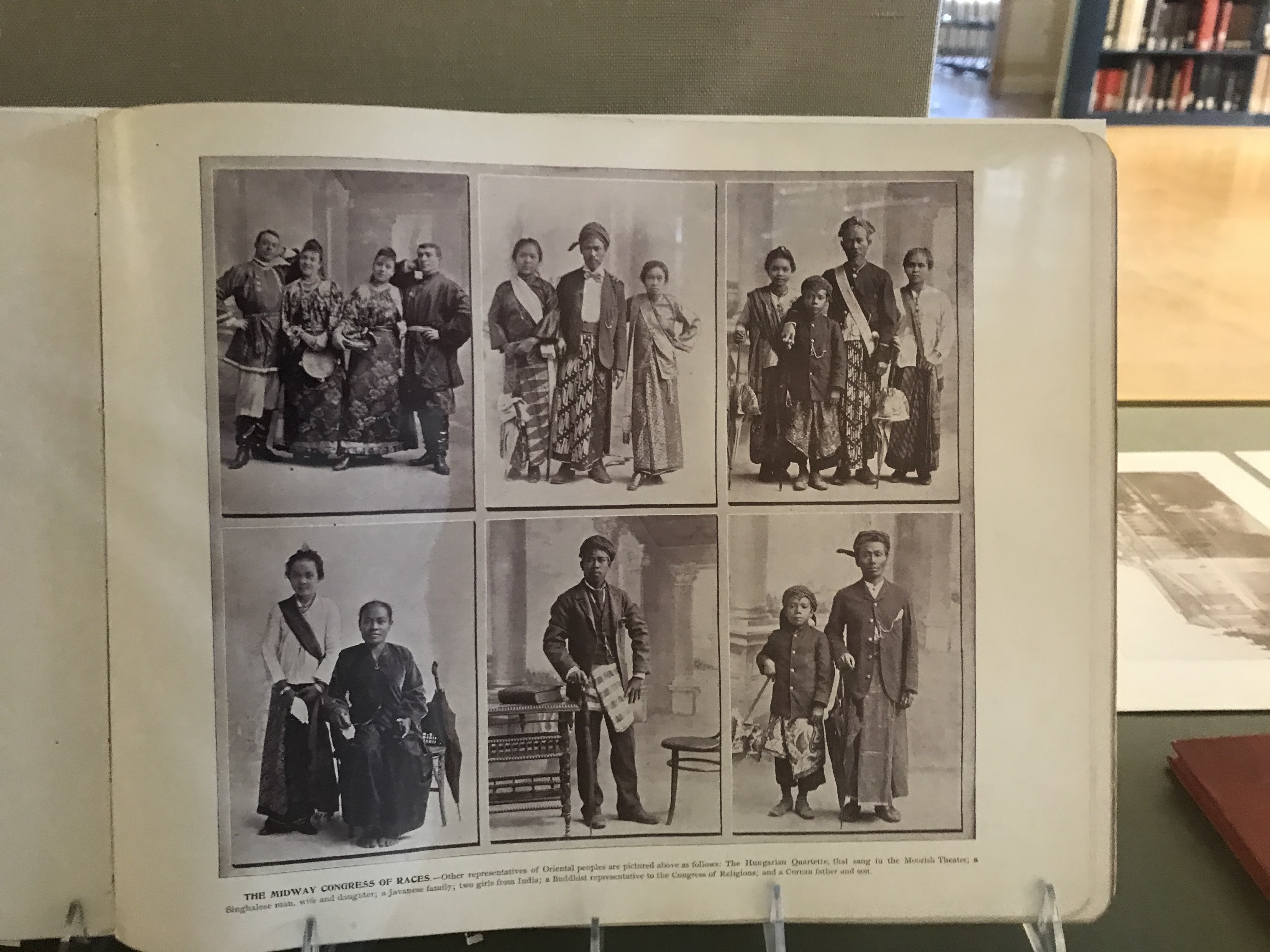

The “Congress of Races” on the Midway (Chicago, 1893)

Perhaps the most famous element of the Columbian Exposition in Chicago was the

mile-long Midway Plaisance, which stretched west from the main lagoons and

buildings. In addition to the Ferris Wheel and other amusements, the Midway

contained exhibits of foreign and exoticized peoples, from the “Japanese Bazaar”

and “Street in Cairo” exhibits to living displays of colonial subjects in Africa and

Southeast Asia. The figures shown here use gesture and costume to perform ethnic

and racial character types for the camera. The Midway enticed American visitors

with its promise of a kaleidoscope of cultural difference.

J.W. Buel. The Magic City: A Massive Portfolio of Original Photographic Views of the Great World’s Fair and Its Treasures of Art, Including a Vivid Representation of the Famous Midway Plaisance. St. Louis: Historical Publishing Company, 1894. Archives & Special Collections Library, Vassar College

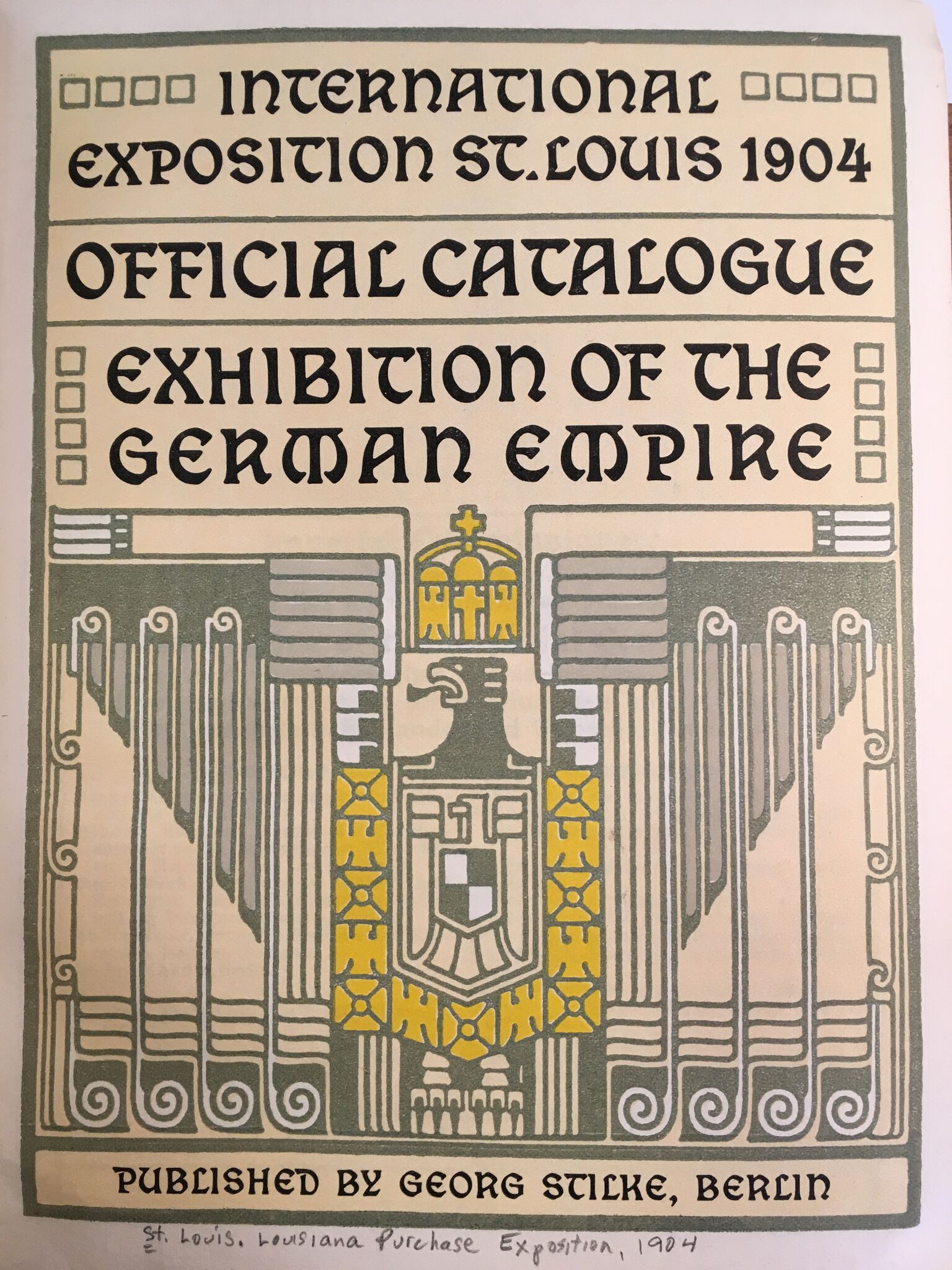

The German Empire exhibition in St. Louis (St. Louis, 1904)

As a celebration of a historic agreement between France and the United States, the

Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904 did not initially elicit interest from the

German Empire. Yet after some hesitation, emperor Wilhelm II committed to a

significant German display at the fair. Although Germany’s selection of art skewed

traditional (leaving out contemporary artists such as Max Klinger), the Official

Catalogue presents a more modern face. Designed by architect and designer Peter

Behrens, the book’s geometric ornament points beyond the curvilinear Art

Nouveau style that dominated much fair design around the turn of the century (see,

for example, the Alphone Mucha stamps below).

International Exposition St. Louis 1904. Official Catalogue. Exhibition of the German Empire.Peter Behrens, designer. Berlin: Georg Stilke, 1904. Vassar College Libraries

Poster stamps of the fairs (St. Louis, 1904; Seattle, 1909)

Fairs around the turn of the century often turned to the poster

stamp—a small but graphically bold form of printed

ephemera—to advertise and commemorate the events. Czech

artist Alphonse Mucha used his characteristic Art Nouveau style

for these rare 1904 stamps for the world’s fair in St. Louis. (An

earlier world’s fair, the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris, had

helped “le style Mucha” first gain international recognition.)

Below, three circular poster stamps display the official logo of the

Alaska-Yukon- Pacific Exposition, which celebrated Seattle’s ties

to trade, gold, and industry in the Pacific Rim. Three women

represent Japan (left, holding a ship), Alaska (center, holding

ore), and the Pacific Northwest (right, holding a train).

Louisiana Purchase Exposition poster stamps. Alphonse Mucha, designer.

Published by Adolph Selige Souvenir Card Co., St. Louis, MO. 1904

Collection Arthur H. Groten

Alaska-Yukon- Pacific Exposition poster stamps. 1909

Archives Special Collections Library, Vassar College

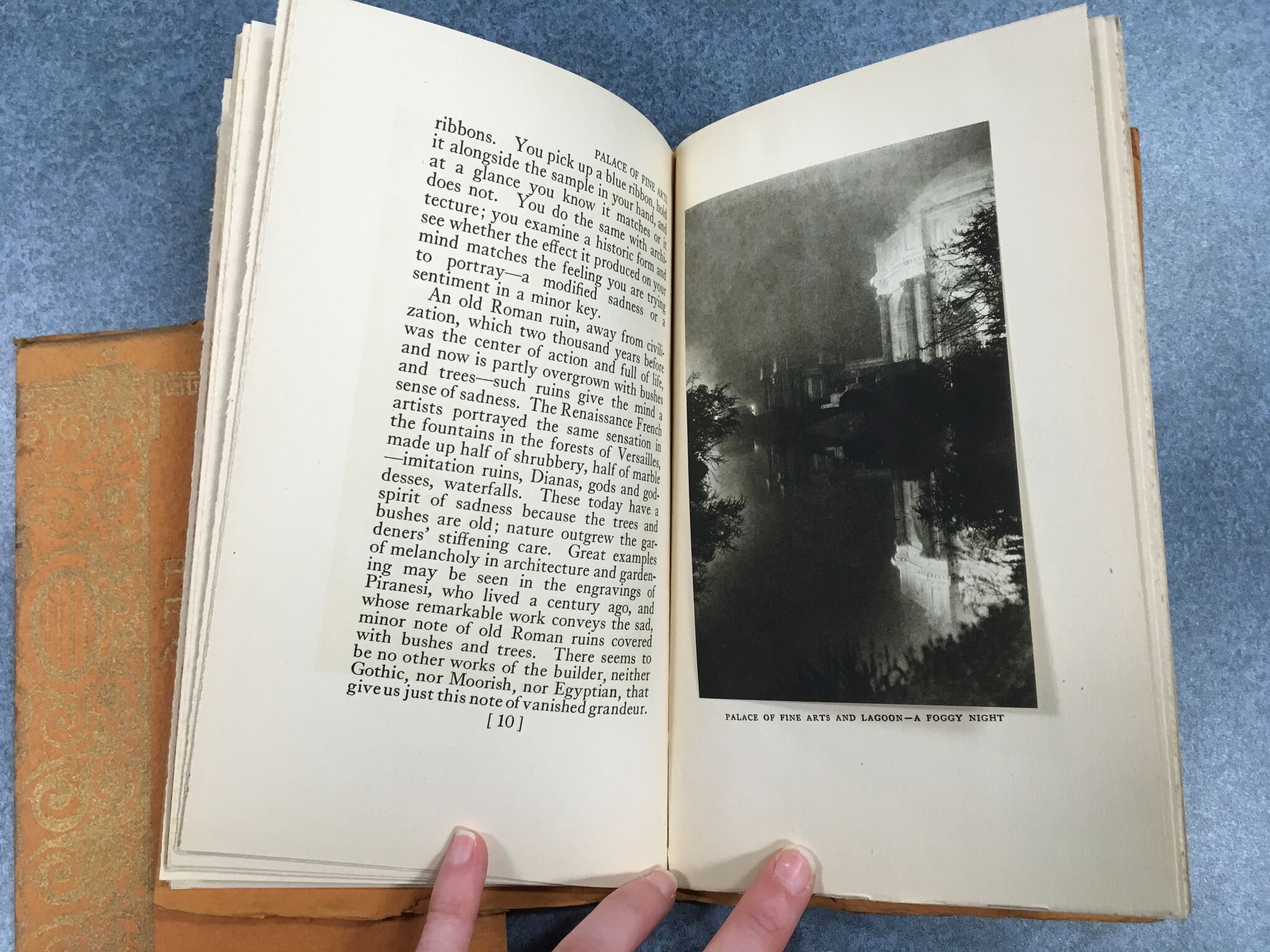

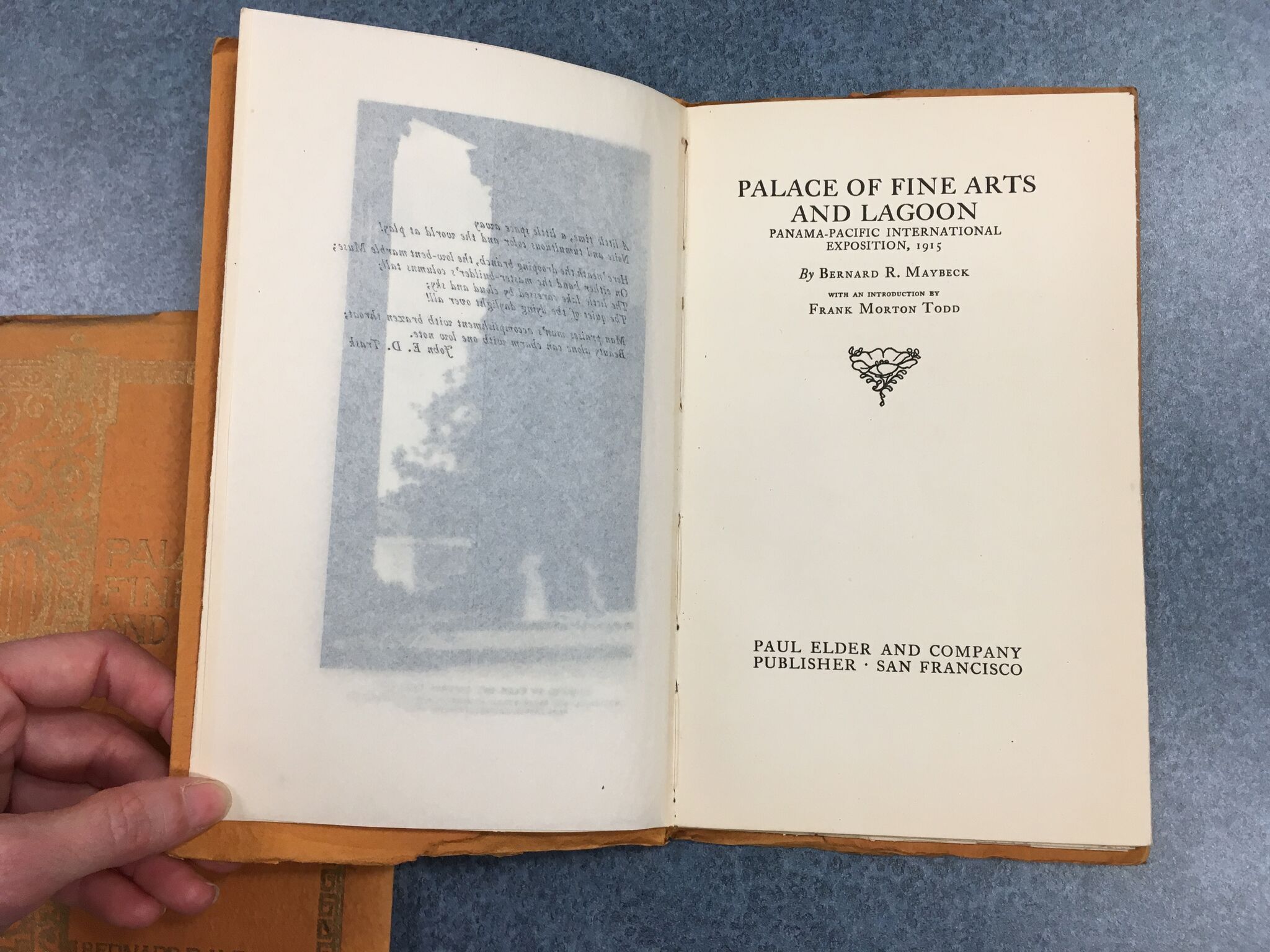

Art and architecture at the Panama-Pacific (San Francisco, 1915)

Paul Elder and Company published a suite of books documenting the art, architecture, sculpture, and landscape design at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. The books’ ornament, curving typeface, and gold lettering echo the color and romance of the fair itself, which was dubbed “Jewel City” for its use of outdoor color and lighting effects. Helen Wright, who owned many of the Vassar copies, obtained the signatures of architect and landscape designer L. C. Mullgardt, painter Eugen Neuhaus, architect Bernard Maybeck, and sculptor A. Stirling Calder, all of whom oversaw designs or contributed work at the fair. Maybeck’s Palace of Fine Arts, visible in the photograph, offered a melancholy retreat in which to view art, complete with a lagoon site and decorative funereal urns along the base of the rotunda.

Bernard R. Maybeck. Palace of Fine Arts and Lagoon, Panama-Pacific International Exposition. 1915 (2 copies)

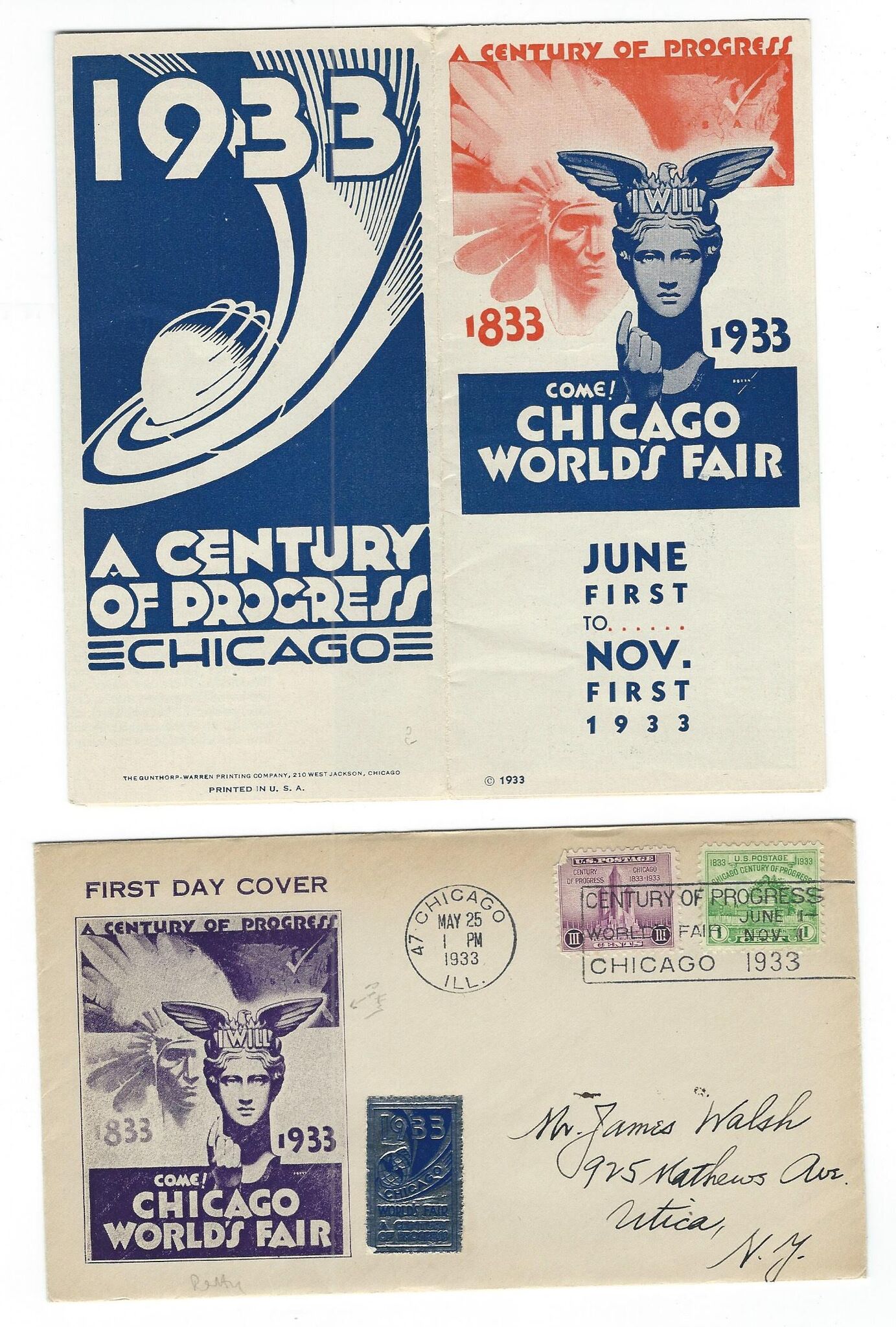

A Century of Progress (Chicago, 1933)

If earlier expos sought to balance the forces of tradition and modernity,

fairs of the 1930s came down firmly on the side of modernization. At A

Century of Progress, held to commemorate Chicago’s centennial in 1933,

modernity’s effects permeated the grounds, from the streamlined and

International Style architecture to the prominence of the corporate pavilion.

Innovations included the enormous suspended roof of the Travel and

Transport Building (rendered here on a poster stamp and spoon handle) and

pavilions designed as giant product advertisements, such as the Havoline

Thermometer Building, topped by a 200-foot- tall working thermometer

(see poster stamp). Nevertheless, older themes continued, in the popular

Fort Dearborn display (see spoon and poster stamp) and, most notably, in

the official poster design by George B. Petty, which recalled nineteenth-

century imagery of Native Americans as a people doomed to vanish. In the

design (reproduced here on a brochure, envelope, and poster stamps),

Chicago’s “I Will” maiden, sporting the city motto in her crown, displaces

the Native American figure in the name of so-called progress.

Poster stamps (4), “Chicago World’s Fair.” George B. Petty, designer. 1933

Poster stamp, “A Century of Progress / Merck Exhibit in the Hall of Science.” 1933

Poster stamps (8), “1933 Chicago.” 1933

Brochure and envelope. Gunthorp-Warren Printing Company, Chicago. 1933

(Archives & Special Collections Library, Vassar College)

Commemorative spoon. Oneida Community Par Plate. 1933

Commemorative spoon. Green Duck Co., Chicago

(Private collection)

World of Tomorrow peepshow (New York, 1939)

While most objects from the New York World’s Fair of 1939 reflect the official

theme of “The World of Tomorrow,” this children’s book uses a decidedly

anachronistic form, the tunnel book or “peepshow.” Popular in the late eighteenth

and nineteenth centuries, paper peepshows could be unfolded like an accordion,

revealing a diorama-like scene for viewers looking through the aperture (see

photograph). Here, Martha and George Washington—whose inauguration as

president in 1789 in New York was the nominal occasion for the fair—peer into

the future to see the fair’s main axis with the Trylon and Perisphere in the distance.

1789-1939:

The World of Tomorrow, New York World’s Fair. 6-panel peepshow. Elizabeth Sage Hare and Warren Chappell, illustrators. New York [?], ca. 1939. Archives & Special Collections Library, Vassar College

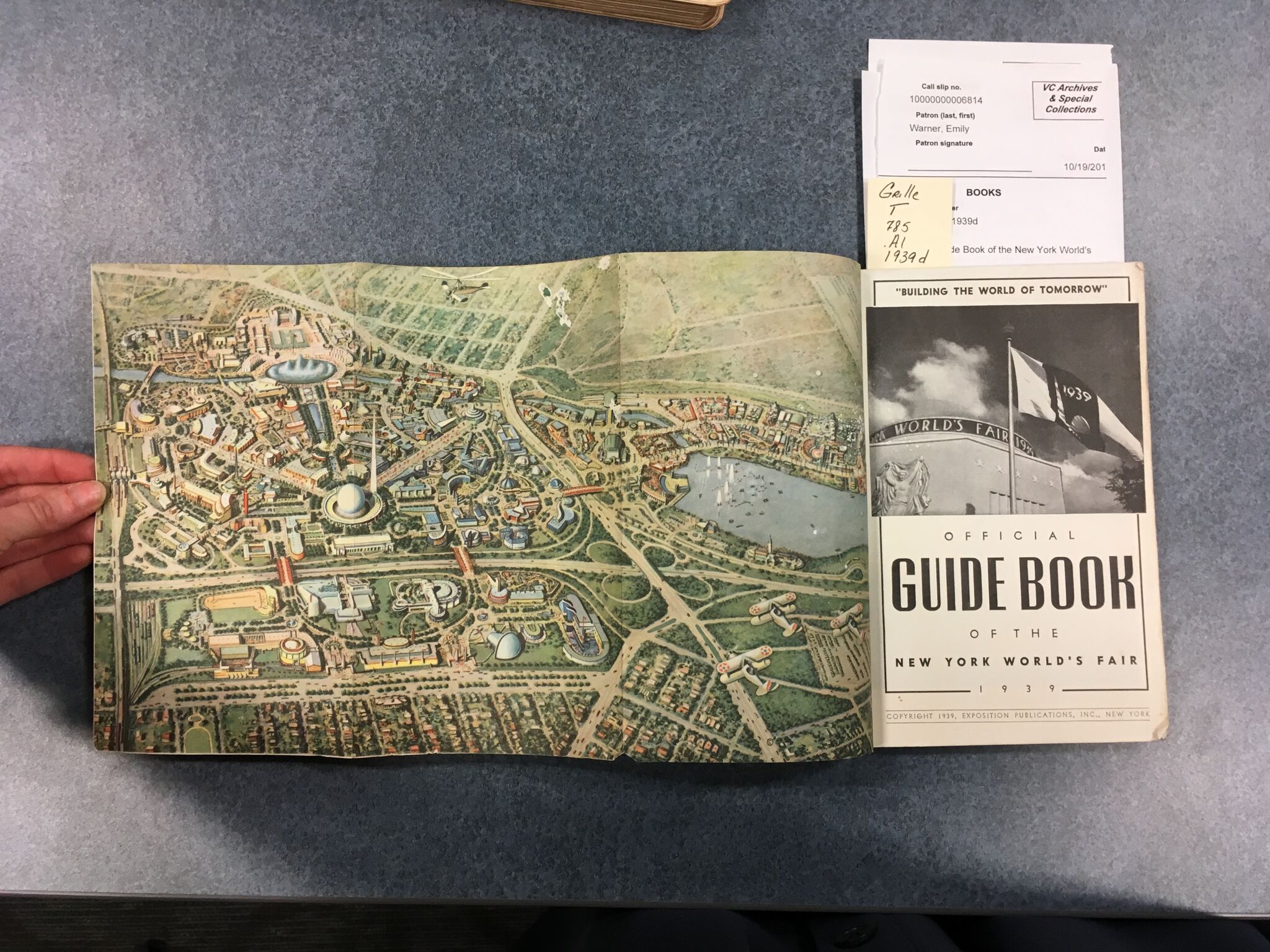

This guide includes a double-sided map of the 1939 New York World’s Fair, with

an aerial view of the pavilions on one side and a color-coded schematic on the

reverse. Note the Trylon and Perisphere at left, the iconic centerpiece of the

fairgrounds.

Official Guide Book of the New York World’s Fair, 1939. New York: Exposition Publications, 1939. Archives & Special Collections Library, Vassar College

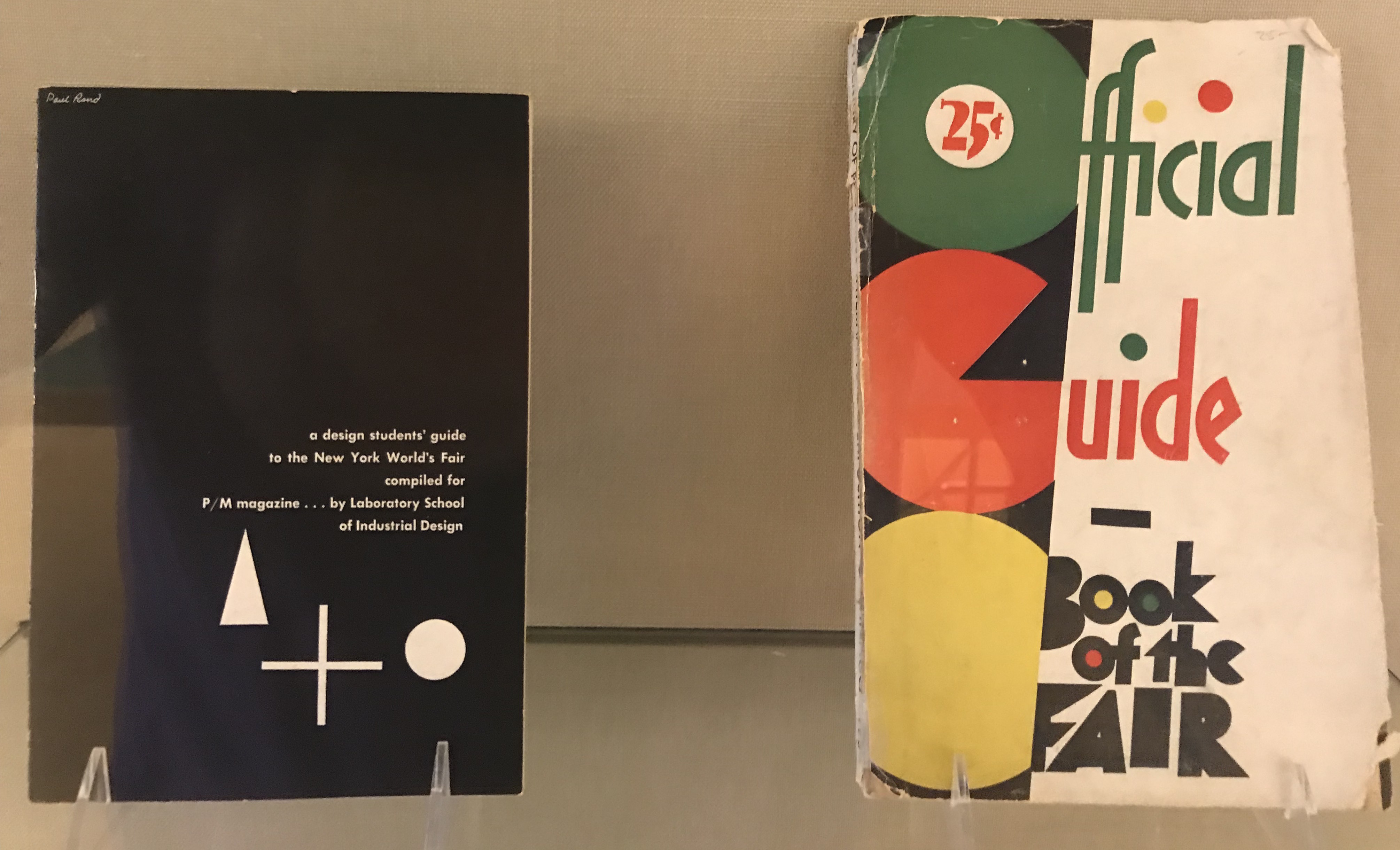

The fairs of the 1930s were an opportunity for bold, modern designs in posters and

guidebooks. The Laboratory School of Design’s Design Student’s Guide to the

1939 New York World’s Fair, published as an insert in P/M magazine,

championed those exhibits that showed “fresh ideas in architecture, industrial

design, display and similar fields.” The guide defines truly modern design in

contrast to the “modernistic” (overdone Art Deco) and the “modernoid”

(excessively streamlined profiles). The cover, by Paul Rand, is an iconic image in

graphic design; note the simplified version of the fair’s Trylon and Perisphere.

John McAndrew, designer of the Van Ingen Art Library (1937) and professor of

architecture at Vassar from 1931-37, wrote the introduction.

Official Guide Book of the Fair. Chicago: A Century of Progress Administration Building, 1933 Private collection

A Design Student’s Guide to the New York World’s Fair. Paul Rand, designer. Introduction by John McAndrew. New York: Laboratory School of Industrial Design and P/M magazine, 1939 Archives & Special Collections Library, Vassar College

The World’s Columbian Exposition Illustrated (Chicago, 1893)

The World’s Columbian Exposition Illustrated published updates on the 1893 fair,

from construction news to attendance figures and special events. On the cover of

this issue, published four months before opening day, Chicago is visually identified

with the nation: the fair’s Administration Building, at left, mirrors the U.S. Capitol,

and an allegory of Chicago accepts souvenir coins from Uncle Sam. In the banner

along the top, Columbus’s arrival in the New World (the event that the fair

commemorated) is contrasted with Chicago’s modern cityscape and smoking

factories.

The World’s Columbian Exposition Illustrated. No. 23 (January 1893)

Archives & Special Collections Library, Vassar College

What a wonderful display. The Spirit of Niagara is absolutely beautiful. Well done to Ms. Warner and the students of Art 385.