Food sovereignty as a way of overcoming colonialism in Inuit food systems

|

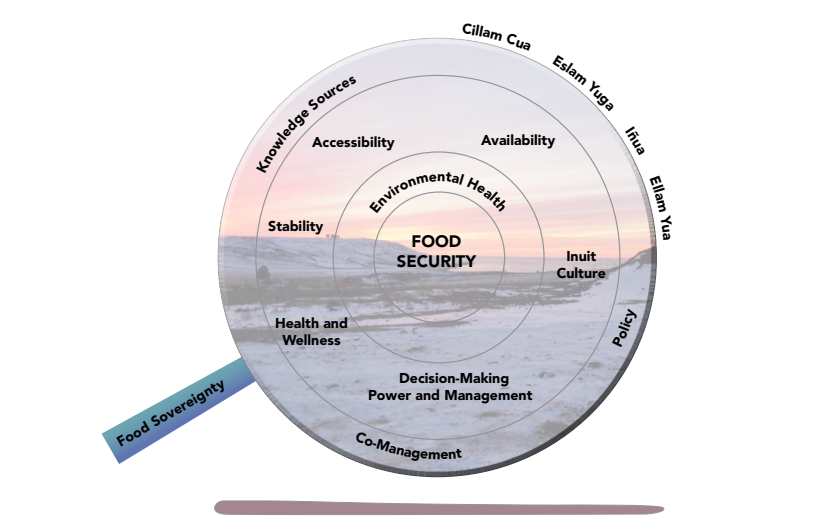

By Lisa Smart and Taylor Worthington “Hunting is what saved the Inuit from starvation…For this reason, the Inuit never forget the value of food.” These are the words of Inuit activist Lessee Papatsie (Del Bello 2017). Although food has always played a central role in Inuit culture, the ongoing effects of colonization together with climate change have made maintaining both food security and sovereignty a daily struggle. Traditional food subsistence practices are increasingly giving way to Western diets consisting of store-bought, nutritionally insufficient foods. As traditional food knowledge dissipates, mental and physical health challenges accumulate. Inuit communities across the Arctic (Figure 1) are now actively working to mitigate this issue with community-based movements towards total food sovereignty.  Figure 1. Map of Inuit Regions in Northern Canada. The Nunavut region is highlighted yellow (Statistics Canada 2013). Colonial influence in Inuit communities began as early as the eighteenth century with the introduction of European whalers and explorers eager to sell goods, guns, and steel tools to Inuit communities. This caused a decline in the use of traditional tools and hunting tactics. Colonial practices of the Canadian federal government forcibly relocated Inuit communities into isolated areas further north of their homelands and brought a wage economy, permanent settlements, and residential schools. These all contributed to a loss of culture and transmission of indigenous knowledge. Subsistence practices changed drastically as snowmobiles and powerboats replaced dogsleds and kayaks, and foreign food shipments replaced local food sources (Lougheed 2010; Robinson 2018). Reliance on colonial food systems is increasing with climate change. The Arctic is experiencing climate change at one of the fastest rates. Erratic and unpredictable seasonal changes are introducing new diseases among wildlife and interfering with the migratory patterns of key food sources including caribou, seals, and whales (Del Bello 2017). Community enforced harvest restrictions aiming to protect some of these animals like the caribou are increasing reliance on store foods, reducing income opportunities, interrupting sharing networks, and limiting opportunities for younger generations to acquire harvesting skills (Ford et al. 2019, 551). Oil exploration is also driving a population boom, thereby stretching thin already unreliable food supply chains (Del Bello 2017). With greater household crowding, the amount of food required increases, and so, poorer households are pushed to rely more on cheap store foods. Although Inuit communities attempt to maintain food sharing networks (Figure 2), the influx of individually packaged, easy to prepare store-bought food contributes to the breakdown of these collaborative networks upheld by subsistence practices (Ford et al. 2019, 550).  Figure 2. Inuit community sharing frozen and aged walrus meat (Robinson 2018). As Inuit people are driven to rely on colonial food systems, numerous repercussions emerge. A small market basket of produce, bread, butter, and potatoes costs over double in Nunavut than anywhere else in Canada, and much of the produce is already rotting by the time it makes its way north (Figures 3 & 4) (Qikiqtani 2019, 6). This means that most residents opt for cheap yet less nutritious and calorically-high foods like pasta and rice. Managing hunger through these colonial food systems sacrifices their best sense of who they are and leaves Inuit people vulnerable to a host of health problems (Del Bello 2017).  Figure 3. A high priced jug of orange juice at a grocery store in Iqaluit, Nunavut under the Nutrition North Canada program (Kenny & Lemieux 2017). The traditional Inuit diet of berries, caribou, seals, whales, and birds is extremely healthy and provides important vitamins and micronutrients (Brubaker et. al 2011, 43). Reliance on imported store food has led to food insecurity rates of over 70% in Nunavut, making communities more susceptible to obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and depression. This also comes with detriment to cognitive, academic and psychosocial development among children (Qikiqtani Inuit Association 2019, 5; Inuit Tapiriit 2019, 11). The physical activity and nutritious food obtained through hunting and gathering is essential for mental health and cultural meaning-making.  Figure 4. Families in Nunavut protesting disproportionately high food prices and unhealthy options (Freeman 2015). For the people of the Arctic, traditional foods are much more than calories or nutrients; they are a lifeline for their culture and reflect the health of the entire Arctic ecosystem (Inuit Circumpolar 2015, 8). A give and take with the land, ice, sea, plants, and animals is an essential part of how these people make meaning in their life. The dwindling capacity for elders to pass down knowledge to younger generations about surviving from the land is depressing the spirit of the Inuit people. Subsidization and assistance programs from the Canadian government do not comprehensively address these issues. Nutrition North Canada contributed less than one percent of its budget to increasing access to traditional foods, preferentially supporting market driven models and supplying imported factory farmed animal protein (Qikiqtani 2018, 6). Rates of food insecurity in Nunavut have actually increased by 13.2% since the launch of the program (Ford et al. 2019, 550). Evidently, western methods of solving food insecurity are only exacerbating the problems instigated by colonialism. This is why the need for Inuit-led food sovereignty programs intended to share indigenous knowledge and revitalize traditional subsistence practices has never been greater. The objective now must switch from food security to food sovereignty. The Nunavut Agreement objective for food sovereignty revolves around providing rights for Inuit to make decisions about the use, management, and conservation of their land, water, and natural resources (Qikiqtani 2018, 4). This means empowering Inuit to feed their own communities and supporting acts of subsistence as a valued part of a conservation economy. Organizations like the Qikiqtani Inuit Association are looking to make harvesting a paid position, providing they develop marine infrastructure, training facilities, and food processing plants (Ibid, 11). In the meantime, the Inuit are working to supplement their diets with fresh produce grown in community greenhouses. This provides an outlet for nutritious food without reliance on high priced and inconsistent shipments of store foods (Brubaker et al. 2011, 43).  Figure 5. The Inuit Circumpolar Council’s depiction of food security as a drum composed of interconnected components of indigenous knowledge and environmental health. It is supported by the handle of food sovereignty (Inuit Circumpolar Council-Alaska 2015). Throughout Northern Canada and the Arctic, colonialism lives on in the way that food is distributed and controlled within Inuit communities. Policy decisions are not representative of Inuit culture, and governmental authorities lack a comprehensive understanding of the holistic nature of traditional food systems. Dr. Dalee Sambo Dorough, International Chair of the Inuit Circumpolar Council, says that Inuit reclamation of their own means of subsistence is therefore “directly and intimately linked with [their] right of self-government and [their] right of self-determination” (Cultural Survival 2020). This right to decision making is part of an interconnected framework of practices and values that work to ensure sustainably-harvested, culturally-appropriate, and nutritious food for all Inuit peoples. Works Cited Brubaker M, Berner J, Bell J, Black M, Chaven R, Smith J., Warren J. 2011. Climate Change in Noatak, AK, Strategies for Community Health. ANTHC Center for Climate and Health. 1–54. http://anthc.org/wpcontent/uploads/2016/01/CCH_AR_062011_Climate-Change-in-Noatak.pdf Cultural Survival. 2020. Indigenous Food Security in the Arctic. Cultural Survival. https://soundcloud.com/culturalsurvival/indigenous-food-security-in-the-arctic. Del Bello L. 2017. Globalisation and global warming threaten Inuit food security. Rethink. https://rethink.earth/globalisation-and-global-warming-threaten-inuit-food-security/ Ford JD, Clark D, Naylor A. 2019. Food insecurity in Nunavut: Are we going from bad to worse? Canadian Medical Association Journal. 191(20): 550–51. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.190497 Freeman, Sunny. 2015. 1 in 3 Suffer from Food Insecurity in Nunavut, StatsCan Data Reveals. Huffingtonpost. https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2015/03/25/food-insecurity-canada_n_6940384.html. Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. 2019. National Inuit Climate Change Strategy. Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. 1–44. https://www.itk.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/ITK_Climate-Change-Strategy_English_lowres.pdf Inuit Circumpolar Council-Alaska. 2015. Alaskan Inuit Food Security Conceptual Framework: How to Assess the Arctic From an Inuit Perspective: Summary Report and Recommendations Report. Anchorage, AK. https://iccalaska.org/wp-icc/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Food-Security-Summary-and-Recommendations-Report.pdf. Kenny, Tiff-Annie, and Tad Lemieux. 2017. Rocket Debris Is a Risk to Inuit Food Security. Intercontinental Cry. https://intercontinentalcry.org/rocket-debris-risk-inuit-food-security/. Lougheed, Tim. 2010. The Changing Landscape of Arctic Traditional Food. Environmental Health Perspectives. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2944111/. Qikiqtani Inuit Association. 2018. Food Sovereignty and Harvesting. Qikiqtani Inuit Association, 1–21. https://www.qia.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Food-Sovereignty-and-Harvesting.pdf Robinson, Amanda. 2018. Country Food (Inuit Food) in Canada. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/country-food-inuit-food-in-canada. Statistics Canada. 2013. Four Regions of Inuit Nunaat. StatCan. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-634-x/2008004/figure/6500054-eng.htm. |