It shouldn’t take much brain power to reason why Columbia Pictures produced Jason and the Argonauts as a fantasy epic in the early 1960s. As one of the oldest known hero tales, Jason’s quest is chock full of what we would nowadays consider archetypal elements of the genre: the stoic protagonist, the repulsive villain, a dangerous romance, a clearly defined objective, impossible odds, and of course, a series of treacherous obstacles that provide the spectacle. In short, it’s an easy sell. As you can see, the theatrical trailer does a swell job of consolidating these appealing features into a vibrant, exhilarating package:

As is the case with any cinematic adaptation of an ancient story, the filmmakers were tasked with consolidating numerous variations of the Jason legends into a single narrative. Likely originating in Thessaly, these myths began as oral traditions either in or before the time of Homer, as indicated by a passing reference to the hero in The Odyssey (1). Only in the 3rd century BCE did the poet Apollonius compile the legends into a physical text, the Argonautica, and later they were retold as part of Ovid’s Metamorphoses in first-century Rome (2). Across all versions, however, the basic plot remains consistent. In order to reclaim sovereignty of Iolchus from the grasp of his murderous uncle, Pelias, Jason must embark on a globe-trotting quest to retrieve the legendary Golden Fleece of Colchis. Commissioning the construction of the vessel Argo and assembling fifty men of divine descent (including Heracles), Jason sets sail on the voyage which will test the limits of his capabilities. His challenges are great, but thankfully his allegiances mount along with the peril. He receives limited aid from a goddess (sometimes Athena, sometimes Hera, sometimes Aphrodite), befriends the blind prophet Phineas, and, upon reaching Colchis, allies himself with the sorceress Medea, the daughter of King Aeetes. After a series of bouts with the hostile king, Jason finally claims the fleece and returns home to rule Iolchus, but not after suffering a great deal of loss and hardship along the way.

The 1963 film retains all of these essential plot beats, and while some major liberties are taken, it generally adheres to the popular versions of the legend. A great deal could be written about the numerous choices made in reconstructing the story for a modern moviegoing audience, but for our purposes, we are going to zero in on one of the film’s most memorable components. No, not Jason. Not Argonauts, either. I’m talking, of course, about the mountainous man of bronze, Talos.

There’s a wealth of reasons why Jason and the Argonauts continues to entertain over half a century later, and Talos is most certainly one of the biggest. Literally. Brought to life through the inimitable stop motion effects of the late, great Ray Harryhausen, the towering Talos appears early in the film to give the Argonauts a considerable thrashing after Heracles unwittingly disturbs his slumber. It’s generally unwise to steal broach pins from the gods for use as a javelin, but Heracles evidently didn’t get that particular memo:

Talos, of course, has a history deeply rooted in classical Greek myth. Often considered the earliest conceptualization of a robot, Talos is usually found associated with the gods Hephaestus and Zeus. Sometimes he’s a leftover of the Zeus-created bronze generation, other times he’s the offspring or father of Hephaestus, sometimes he’s a gift from Zeus to King Minos, other times a gift from Hephaestus to Zeus – the permutations are endless (3). Regardless of the myth, however, one connection remains consistent: the Cretan word from which Talos derives his name – talios, meaning “sun” – was frequently used by those islanders as a name for the king of the gods himself (4). Not only does this shared use of the term allude to the giant’s immense power, but it also hints at his role as a somewhat paternal figure. Indeed, Talos was known as the tireless guardian of Crete, a sentinel who would circumambulate the island three times daily to moderate the behavior and livelihood of its citizens (5). Moreover, he would vigorously defend his land from any intruders, and in keeping with his solar-derived name, his preferred method of executing perceived threats was, by all accounts, incineration. Depending on who you ask, the giant would either snatch up poor souls and leap with them into a flaming vat, or he would heat up his own metallic body to incredible degrees and scorch his opponents through mere physical interaction (6). His love of turning folks to ash was unfortunately excised from his on-screen debut, but that does not make his appearance in the film any less memorable.

Though traditionally depicted as Crete’s conservator, Jason and the Argonauts finds Talos holding watch over the aptly named (and movie-created) “Isle of Bronze,” placed there by Hephaestus to guard Zeus’s armory. Ironically, despite his role here as the Argonauts’ inaugural challenge, Talos almost always appears much later in the story as a part of the return voyage (7). However, seeing as how the film only tackles the trip to Colchis (perhaps musings of a sequel prompted the studio to hold off on the return journey), his placement at the front feels appropriate. After all, Talos provides a rather fitting transition into the more fantastical side of this mysterious world. Sure, by this point we’ve been introduced to the pantheon, but thus far nothing about the Earthly realm appears too far removed from our own reality – that is, until the deceptively inanimate statue pivots its enormous head. It’s a genuinely chilling moment; you can watch above how this gradual, creaky awakening shatters both the heroes’ and our sense of (relative) normalcy to eerie effect.

The scene really does live or die by the physical depiction of Talos, and with regards to visual reference the filmmakers were extremely limited. Interestingly, while Talos is very often described throughout mythology as a humanoid giant, the few remaining images we have depict a figure of somewhat different form. Remember when I mentioned how every day Talos would circle the island three times? Well apparently having him be enormous still didn’t make that feat likely in some peoples’ eyes. As such, we have a few surviving coins featuring images of a Talos with billowing, eagle-like wings.

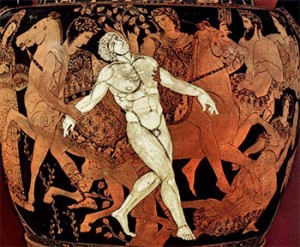

We also have this vase from around the 4th century BCE, which depicts Talos’ death (more on that in a minute). We see here, while he might be a tall fellow, he isn’t the colossus we usually have in mind when we think of Talos. He definitely isn’t big enough to lift the Argo with a single hand, as he does here!

Obviously these artifacts are invaluable from a historical standpoint, but Harryhausen made the right choice going down the lumbering giant route. For one, the film already has both winged and human-esque antagonists (the harpies and a skeleton army, respectively). Talos in this form is simply unlike anything else in the movie, and furthermore unlike anything from the entire Harryhausen monster catalogue. But, more importantly, this was a prime opportunity to demonstrate a complex level of stop motion animation that both enhanced the cinematic elements of the story and recalled the nature of the character from the ancient myths. It is a presentation that not only boasts impressive scale, but also one that emphasizes Talos’s placement between the living and the mechanized. His stiff, ungainly movements become a much more noticeable part of his character when magnified to this degree, which is entirely apt considering that the ambiguity of his not-quite-human, not-quite-mechanical existence plays a large part in his ultimate downfall – just like in the myths.

You see, Talos might be made of bronze, but he draws his life force from a single vein flowing down his back to his heel, where it is stopped by some sort of large plug. Whether described as a nail or a pin, that plug naturally gets pulled at some point by one of the heroes, thus draining Talos of life. In many cases that hero is Medea, who uses trickery to deceive the living statue, while in others it is the Argonaut Poeas who knocks out the stopper with his trusty bow and arrow (7). Seeing as how the adventurers have yet to encounter Medea at this point in the film and that Poeas is absent entirely, the eponymous hero himself takes up the deed, acting under the guidance of Hera. Even disregarding the aforementioned characters’ absences, it makes sense to thrust this duty upon Jason in this context. As his first act of true heroism, the defeat of the Talos establishes Jason as a courageous leader and a man fit for this epic quest – someone capable of navigating the many challenges that lie ahead.

The Argonauts proceed to encounter a series of equally magnificent beasties, but unfortunately I am unable to cover them here due to my rapidly increasing word count. While the battle against the skeleton army is my pick for the film’s absolute crown jewel of visual wizardry, the Talos encounter is an undoubtably impressive display, and one with great reverence for the myths that inspired it.

———————————————————-

Sources:

2. Jason and the Quest for the Golden Fleece

6-7. Theoi.com: Talos