This summer, I worked with Professor Lydia Murdoch on research for her current book project, Called by Death: The Politics and Public Mourning of Child Mortality in Nineteenth-Century England. This will be the first comprehensive history of the Victorians and child death. The book examines the ways in which discourses of grieving for dead children changed over the course of the nineteenth century and, in particular, how women drew upon their experiences of child death as they claimed a greater public role as authorities on political topics ranging from imperial expansion and factory production to working-class housing conditions and state welfare programs. My research this summer centered on women abolitionists in Britain in the nineteenth century. Professor Murdoch and I explored how these British women abolitionists contributed to political expressions of grief through their discussion of children who had died or were separated from parents under slavery.

My work consisted of researching and creating bibliographies of primary and secondary materials on British abolitionists. First, I looked at the Wilson Anti-Slavery Collection of British abolitionist pamphlets, a collection of nearly 500 total pamphlets spanning the entire nineteenth century. I collected pamphlets written by or for women that addressed themes of childhood, child death, and separation of families. Types of pamphlets ranged from Annual Reports of Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Societies to collections of stories and poetry for children, advertisements for Anti-Slavery Bazaars, and reports on the education of slave children. Many of these pamphlets attempted to garner sympathy from British women through depictions of the life of children in slavery, particularly through the scope of motherhood.

Next, I turned to the life of Mary Prince, a freed slave who struggled to survive in Bermuda, Turks Island, Antigua, and finally in England. Commissioned and edited by Thomas Pringle, Secretary of the Anti-Slavery Society, and transcribed by Susanna Strickland Moodie, sister of the historian Agnes Strickland, Prince’s slave narrative was the first account of the life of a black women to be published in Britain. Sarah Salih’s edited edition of Prince’s The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave (1831) provided a foundation for my research into Prince’s life.[1] In her autobiography, Prince equates the separation of slave children from their parents with death as she describes her mother shrouding her children and mourning their loss the day they were separated, making Prince’s story perfect for a project on child death in slavery. I found very few primary sources written about Mary Prince; most are newspaper articles that focus on a libel case regarding the validity of Prince’s narrative. I also collected a variety of secondary sources about Mary Prince; most focused on Prince’s voice and agency in her narrative. Despite the importance of Prince’s voice as a black woman in the British abolitionist movement, she was largely excluded from the movement by white women abolitionists, namely those who wrote the abolitionist pamphlets in the Wilson Anti-Slavery Collection, and she was treated as a victim of slavery rather than a fellow activist.[2]

I then looked through Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates for themes of child mortality and loss in Parliamentary speeches that centered around abolition. Speeches discussing children largely focused on the plights of children who were enslaved from birth.

The final portion of my research focused on the life of Sarah Parker Remond, a black abolitionist from Salem, Massachusetts who gave a series of lectures in Britain from 1859-1866 (See Figure 1). Her lectures focused particularly on the sexual abuse of female slaves and separation of families under slavery, and were recorded in both British and American publicans, including the Warrington Guardian, Warrington Times, Warrington Standard, Anti-Slavery Advocate, Bolton Chronicle, The Morning Chronicle, Manchester Times, The Liberator, among others. As for child mortality, Remond concentrated on the case of Margaret Garner, a slave woman who killed her children rather than see them taken into slavery.[3] The amount of primary sources on Remond’s lecture series is extensive; these accounts speak to Remond’s incredible influence as a black women abolitionist in the public eye during this time.

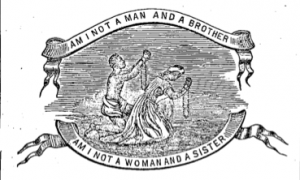

Figure 2- “Am I not a Woman and Sister,” from the Annual Report of the Edinburgh Ladies’ Emancipation Society (1867)

Professor Murdoch will use the sources I collected to write this chapter on women abolitionists and child death and complete her book. This preliminary research has revealed a thick fabric of women’s voices in the British abolitionist movement. However, this fabric is largely dominated by white women’s voices. The pamphlets in the Wilson Anti-Slavery Collection written by white women victimized slaves and elevated white abolitionists. They include startling images of black powerlessness—black women kneeling before white women for aid, or slave children reaching up to the aid of a white woman savior (See Figures 2 & 3).[4] They erased the possibility of black resistance to slavery, which as we know from Mary Prince, Sarah Parker Remond, and countless others, was a powerful force in the abolition of slavery and women’s rights. Nonetheless, through their publications, stories, and lectures mourning the suffering and death of children under slavery, all of these women gained political agency in the public sphere.

[1] Mary Prince, The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave (1831), edited by Sarah Salih (London: Penguin Books, 2004).

[2] Clare Midgley, Women Against Slavery: The British Campaigns 1780-1870 (London: Routledge, 1992), 91.

[3] “Lecture on American Slavery by a Coloured Lady,” Warrington Times (January 29, 1859, no. 4): I.

[4] Midgley, Women Against Slavery: The British Campaigns 1780-1870, 204.