Much of the historiography on U.S. fertility suggests that there was a general “decline” in national fertility rates in the early half of the nineteenth century, before the Civil War [1]. Amidst our four weeks of research however, Professor Edwards and I uncovered novel fertility trends contrary to this generalization, characterized by regional differences throughout the United States.

For the past three years, Professor Edwards and her students have been collecting data on American families from nineteenth-century U.S. census and genealogical records, as part of a larger project investigating the reproductive role of women in U.S. politics and the construction of a continental empire. Using the data that had been collected, this summer, as part of my research, I conducted several statistical analyses to examine how fertility and family structure varied in different regions of the antebellum United States — particularly, the South and the Frontier.

Fertility In her research, Professor Edwards defines fertility as the total number of children born to a woman. Unlike previous studies, which have calculated fertility rates as a ratio of the number of children living to the number of women of childbearing age, we calculated fertility rates based on the number of children individual women reported having in the 1900 U.S. census. This census was particularly useful because it was the first time in history when women were asked how many children they had borne, for official records. The data collected from this census allowed me to work with massive files, oftentimes containing thousands of observations, with detailed information on each mother, including her race, marital status, year of birth, occupation, literacy, and even her husband’s profile.

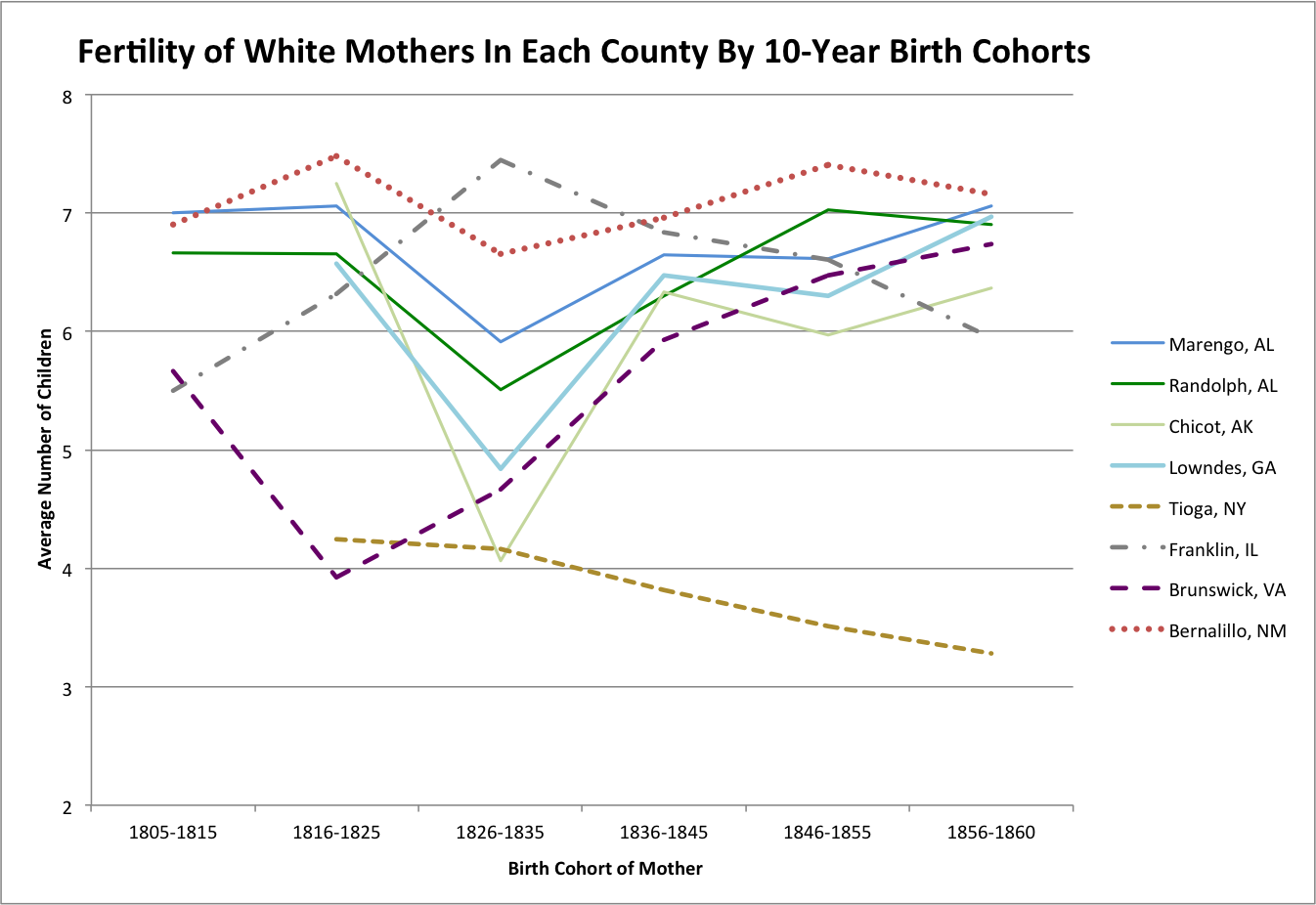

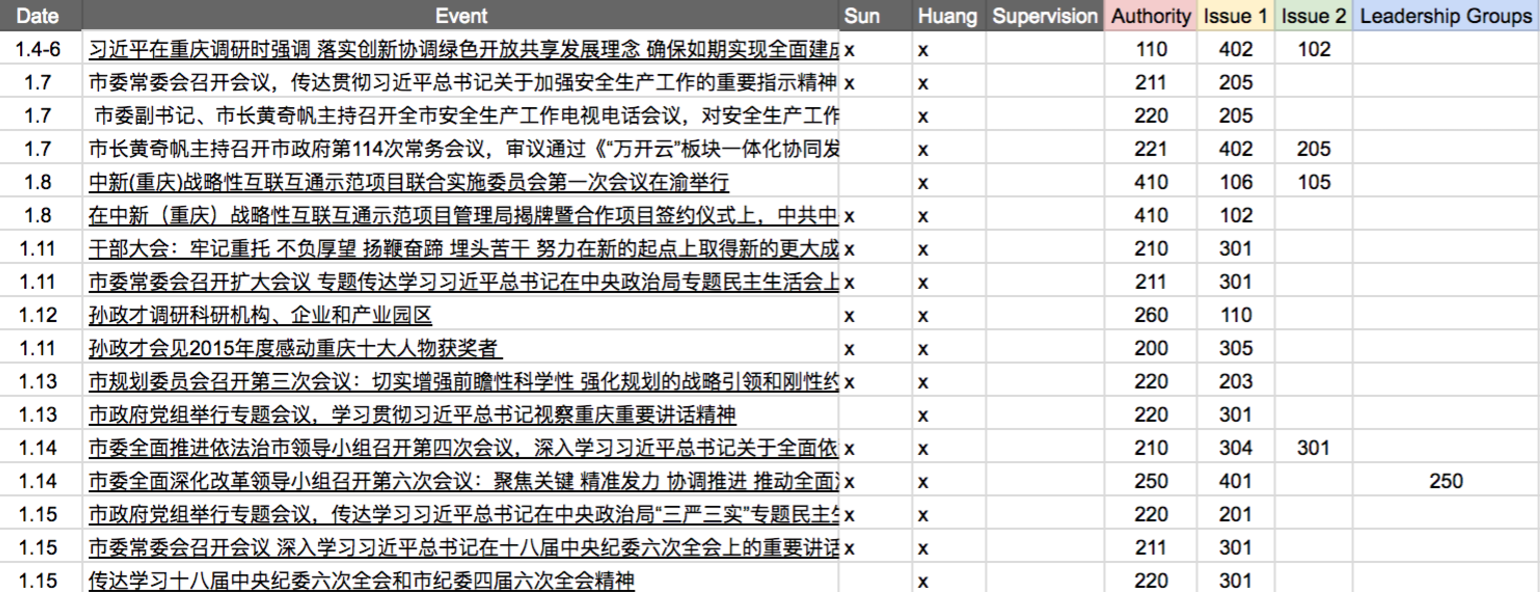

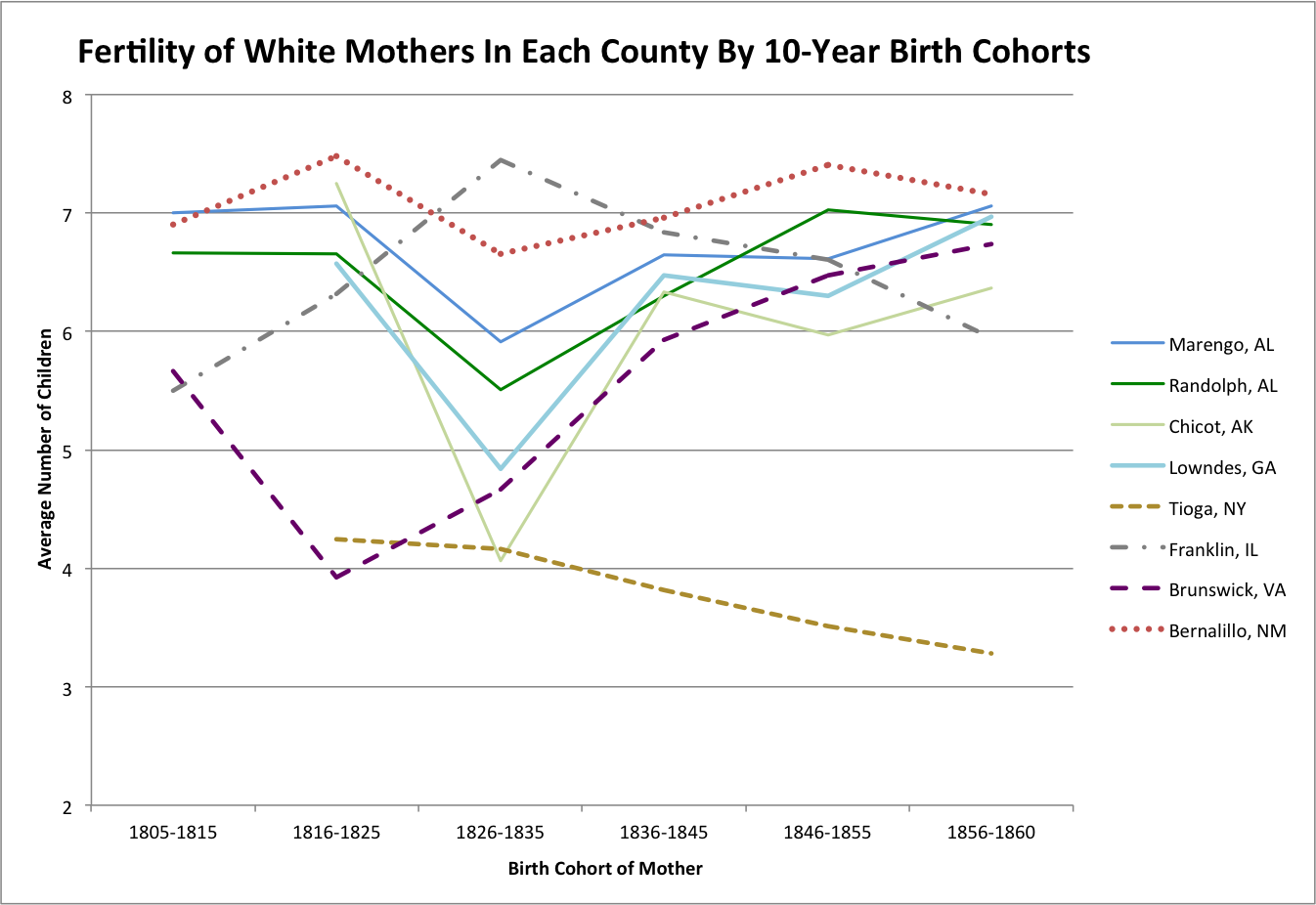

Data on mothers born before 1860, from the following counties, was used to run a series of t-tests in the coding program Rstudio:

- North: Tioga County, NY

- Northwestern Frontier: Franklin County, IL

- Southwestern Frontier: Bernalillo County, NM

- Upper South: Brunswick County, VA

- Deep South: Lowndes County, GA, Chicot County, AK, Randolph County, AL, Marengo County, AL

Analysis of Data Within each region, I specifically evaluated how fertility and family structure differed according to the race, socioeconomic status, place of birth, and education, of mothers, as well as fathers, in some cases. When assessing fertility, it was particularly important to group mothers in each region according to race, since African American mothers, subjugated to the authority of slavery, led drastically different lifestyles when compared to white mothers. Unsurprisingly, our analyses showed that African American mothers, in both the North and the South, on average, had significantly higher fertility, than white mothers. Interestingly, in Bernalillo New Mexico, the only county sampled which included data on Native American and Mexican women, white mothers on average, had significantly higher fertility. These findings were congruent with previous assessments of antebellum fertility based on race.

In order to draw more precise conclusions, we examined several factors within each race, by region. Occupation, for example, was used to measure how socioeconomic status affected fertility. We designated each mother’s occupation as either “agricultural” or “non-agricultural,” assuming that individuals with agricultural jobs were of lower socioeconomic status than those with non-agricultural jobs. We then conducted a t-test to determine whether or not there was a significant difference in the average fertility of the two groups. This was repeated for fathers’ occupations. Aside from this, mother’s place of birth was used to examine women’s mobility and explore whether or not fertility differed between mothers born in a particular region, and those who migrated to that region. Literacy rates of both mothers and fathers, were also examined to determine whether or not fertility differed based on parents’ education. In addition to these factors, we further assessed how family size, difference in age of parents at marriage, and child survival rate, all affected fertility patterns in different regions of the U.S.

The graph above, which illustrates the fertility rates of white women according to their respective birth cohorts, shows that fertility was highest in Western Frontier counties (which we expected due to Frontier conditions and the ideals of Westward expansion), then the South, and finally, the North. Interestingly, in the North, and even on the Western Frontier, factors such as literacy, occupation, and place of birth, all contributed to differences in the fertility of white mothers, in ways that we expected. However, these factors were not significant to the fertility of white Southern mothers. The question of why fertility was so high in the South therefore leads me to the second part of my research this summer — disease.

Browsing through nineteenth-century census maps illustrating the prevalence of certain diseases throughout the United States

Disease According to Todd L. Savitt, professor of History and author of Disease and Distinctiveness in the American South, “The Old South’s health problems were a result of environmental and cultural factors,” which allowed particular diseases to thrive [2]. Such factors contributed to what Savitt calls a “Southern distinctiveness” that separated it from the rest of the country [3]. Indeed, “the inviting physical environment for insect life, the general disregard for the draining of swamps and marshes, and the steady influx of blacks,” all allowed diseases such as malaria, yellow fever, hookworm, and pellagra, amongst many other diseases to remain prominent in the South [4]. Staying within our realm of research, I combed through primary and secondary sources to decipher how these diseases may have affected pregnancy, infant and child mortality, maternal mortality, and family planning, with regards to fertility. However, drawing conclusions using the available data was particularly challenging since during the nineteenth century, diseases were oftentimes misdiagnosed. Additionally, there was little to no information on immunity, access to medicine, child-spacing, stillborn births, and other factors that may have influenced the fertility of the mothers in our dataset. This therefore paves the way for future research!

Professor Edwards and I made numerous discoveries from the sources we came across and data we analyzed over the course of our Ford Project. Although there were limitations to our data, there is still much to discern from it. Our research, which examines fertility in a new way, underscores that fertility trends varied according to specific factors in different regions of the antebellum U.S. Moreover, it gives us insight into the ways in which different groups of women in different parts of the country contributed their reproductive labor to the evolving nation.

[1] Herbert S. Klein, A Population History of the United States, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 68.

[2] Todd L. Savitt, Disease and Distinctiveness in the American South, edited by James Harvey Young and Todd L. Savitt (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1988), 10.

[3] Savitt, Disease and Distinctiveness in the American South, 2.

[4] Savitt, Disease and Distinctiveness in the American South, 9.

Art piece featured at the 2017 Berkshire Conference of Women Historians

2017 Berkshire Conference of Women Historians Prior to our month spent doing research, Professor Edwards and I had the opportunity to attend the 2017 Berkshire Conference of Women Historians, at Hofstra University. Historians from all around the world gathered at the triennial conference to discuss and debate historical and present-day issues relating to women, gender, and sexuality, both within, and outside of academia. I had the privilege of attending a variety of panels, many of which were related to matters Professor Edwards and I were researching, and some of which I was simply intrigued by. In addition to attending these panels, I was also able to meet former Vassar students, now accomplished historians, and learn about their particular fields of research. Attending the conference indubitably allowed me to gain a sense of the vast scope of research that exists amongst women and gender historians, and acquire a greater appreciation for the fascinating work that they do.

– Alicia Lewis’18

e home in Messe Nord at the ICC. Most of the people

e home in Messe Nord at the ICC. Most of the people live in this large room together. The “homes” are 10×10 squares partitioned off by plywood and have no roof. The lights are on from 6am – midnight. Each person gets one small locker for their belongings. Left: The House of World Cultures where the Face It! Konferenz took place. This conference focused on the topics of power-sharing, the production of knowledge, and the questions of what is political and who can be political.

live in this large room together. The “homes” are 10×10 squares partitioned off by plywood and have no roof. The lights are on from 6am – midnight. Each person gets one small locker for their belongings. Left: The House of World Cultures where the Face It! Konferenz took place. This conference focused on the topics of power-sharing, the production of knowledge, and the questions of what is political and who can be political.