Week of 6/2

On Monday and Tuesday, Professor Means and I, along with the other project staff and community members, participated in an intensive run by Kevin Coleman and Dr. Tori Rhoades. The workshop was called “Teaching With Care: Trauma-Informed Pedagogy.” Over the course of those two days we learned strategies and best practices for teaching theater in a therapeutic manner, by participating in exercises, games, performances, and discussions.

On Friday, I attended the Juvenile Justice Counsel at the Poughkeepsie courthouse with CAAD scholars Zander and Taylor, as well as staff member Brian Robinson. Together, we pitched the prototype program to stakeholders, including probation officers, police officers, judges, social workers, and representatives of community organizations.

Week of 6/9

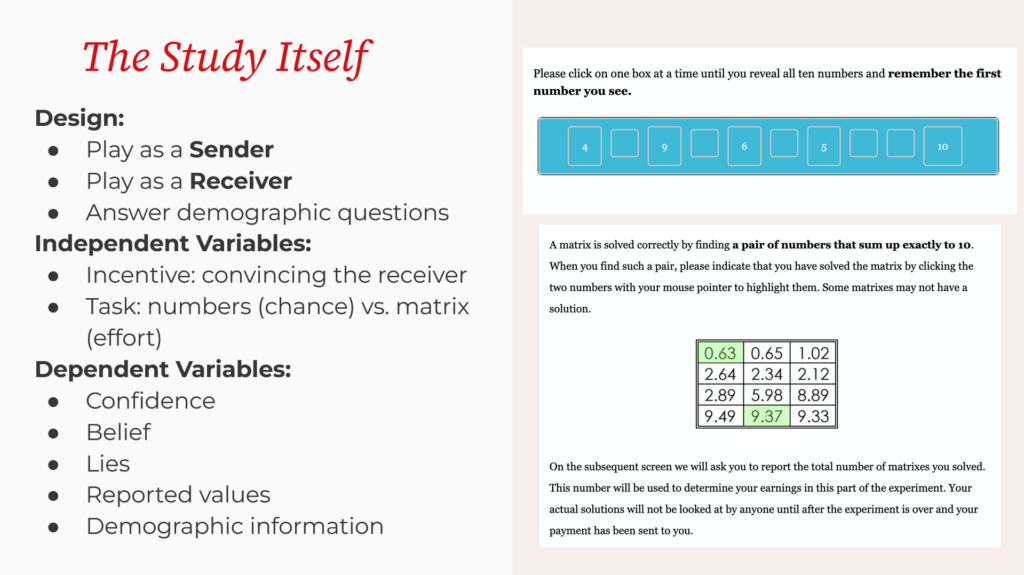

On Monday and Tuesday, I researched and compiled peer reviewed methodologies for similar research projects and experiments in published scholarly articles. I then used what I found to inform and draft an original methodology to be used in our work and future publications.

For the remainder of the week, I drafted the necessary data collection materials to be used in our research. These included intake and exit surveys, intake and exit interviews for students and parents, teacher evaluations, self evaluations, parental consent and minor assent forms. I created these forms based on my previous research into data collection for the parameters the project methodology focuses on, and adapted commonly used questionnaires.

Week of 6/16

Professor Means and I spent this week finalizing the data collection forms. We also wrote and submitted our research proposal to the Institutional Review Board.

On Friday, we attended “Voices of Youth: Educational Justice From Our Youths’ Perspective” at Marist University, which was part of the “Promoting Partnerships to Advance Educational Justice in Poughkeepsie” series. We heard from a panel of seven high school students from Poughkeepsie and Arlington about where they identify needs for students and young people in the community, and their suggestions for improvements. The event affirmed the need for our youth theater program, and further informed the way we plan to run the space.

Week of 6/23

This week, I worked with program administrators Professor Taneisha Means, Brian Robinson, and Tom Pacio, as well as CAAD Scholars Zander and Taylor, to build our program cohort. We received 44 applications and 7 referrals in total. In the end, we built a diverse cohort of 11 students, representing five districts in Dutchess County and a broad array of races, ethnicities, gender identities, and backgrounds.

Additionally, Zander, Taylor, and I spent time working with the program teaching artist Amara James Aja to clarify our respective roles in the rehearsal space and solidify program plans and logistics.

Week of 7/7

After coming back from our Independence Day break, it was time for the program to begin!

As the students ate lunch each day, I administered intake surveys measuring their baseline levels of self esteem, resistance to peer pressure, and mental health. I also conducted one-on-one interviews with each student over Zoom to get to know them better, as well as to qualitatively assess their baseline levels of communication skills, socialization, and self-confidence. Finally, I participated and sat in on programming each day to build trust and connections with the students, as well as to take ethnographic field notes.

On Friday, we took the students to the greenhouse at Vassar, where they had the opportunity to tour the facilities and feed the resident carnivorous plants. We then discussed the college admissions process and our personal experiences with the students, answering any questions they had about their options and giving advice. That evening, we offered an optional field trip to Powerhouse Theater’s performance of The Comedy of Errors. Four students attended, and all enjoyed!

Week of 7/14

During the second week of programming, I continued to attend rehearsals to record field notes. Students started working directly with the text of Romeo and Juliet. They constructed tableaus, performed scenes, and began analyzing themes of power. On the Thursday session, Amara taught a swordfighting lesson (using pool noodles), an exercise I was able to participate in as well. We choreographed fight scenes and practiced safe expressions of violence and nonverbal communication.

On Friday, the students had the opportunity to tour the Loeb and learn more about visual representations scenes through art. They also put their acting skills to use by constructing tableaus to mirror paintings, and were given art supplies to make their own creations. Zander and Taylor then split the students up and held workshops on the performing arts industry and college social life, respectively.

Week of 7/21

In our third week of the program, we saw a lot of major breakthroughs for individual students and the group as a whole! The participants continued to get deeper into scene work and built towards performing a longer scene from Romeo and Juliet. They synthesized what they have been learning about tableaus, power, performing lines, sword choreography, and staging. Their final product was extremely impressive considering the amount of rehearsal time they’d had.

On Tuesday evening, we hosted a dinner for students, their families, donors, and community supporters of the program on the second floor of Gordon Commons. Students were presented with personalized midpoint letters of appreciation from Amara, Zander, Taylor, and myself.

On Friday, the students split into two rotating groups. I took participants down to the Innovation Lab, where they had the opportunity to make buttons, create using the 3D pen and visualizers, and design lithographs and wood burnings. Meanwhile Taylor ran workshops on feelings, needs, empathy, and healthy conflict resolution. At both stations students really got to know one another on a deeper level and found the experience valuable.

Week of 7/28

In our final week of programming, I administered exit surveys to measure changes in their self-esteem and resistance to peer influence from the beginning of the program. I also conducted in person exit interviews with each student to measure changes in their communication skills, socialization, and self-confidence, as well as to hear their thoughts on the program itself as a whole.