Professor Robert DeMaria and Margaret Wagh ’20, English Department

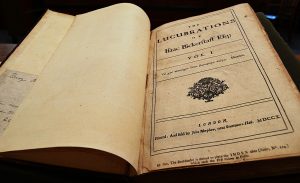

The first page of Vassar College’s edition of the Tatler, a collection of every Tatler published from 1709 to 1711. Courtesy of Vassar College Special Collections.

Under Professor DeMaria’s direction this summer, I explored territory often ignored: the thousands of advertisements living in the 272 pages of the Tatler. I aimed to see what products were considered worthy of ink and to learn more of their advertisers. Often repeating, the advertisements included satirical doctrines, historical books, and moral disputes; also advertised were medicines, lost items, lotteries, wines, and countless ephemeral products.

Over six weeks, I pored over Vassar’s volume of the original folios in Special Collections, occasionally referencing online databases of eighteenth-century works. Professor DeMaria and I agreed an accurate, full transcription of the advertisements was needed before anything else, and so I composed an unprecedented digital collection of every advertisement in the Tatler. Following this recording, I moved towards my main task: the abbreviation of the advertisements.

Professor DeMaria and I agreed that the best method of adhering to the original advertisements while reducing excessive repetition was to place a full abridgment in the newsletter in which it first appears, and to place a shortened title in subsequent appearances; our hope was to convey the advertisements’ importance while condensing their appearances. Following the abridgment process, each advertisement will be placed into its respective Tatler in Professor DeMaria’s edition.

My immersion into the Tatler’s advertisements gifted me an insight into early eighteenth-century London, engaging a historical perspective that cannot be found in any other medium but the advertisements. I watched life change, week by week. It was only through reading each advertisement that I was able to witness the rise and fall of what was relevant to the daily life of Richard Steele’s readers. Hopefully, the advertisements, an often-unappreciated genre, will convey these shifts in London’s society in the Cambridge edition.