From 1798 through the nineteenth century, imperial leaders and the English elite used vaccination as a tool of colonization. Vaccination, unlike public records such as birth and death certificates, gave British military officials the opportunity to track the population in the colonies. As historian Alison Bashford stated in Imperial Hygiene: Critical History of Colonialism, Nationalism and Public Health, “vaccination came to be important as a means for the collection of information through systems of registration and certification of individual infants and children.”[1] What is left untold, however, is how vaccine matter was transported from providence to providence, even from England to the colonies. This summer, I researched how the British used children, mainly native children, to transport and introduce vaccines to India for the health of British children, but also, how it became a colonial, humanitarian campaign to colonize the providence.

By looking at various primary sources such as childrearing guides, medical journals and publications, and newspaper articles from the Times of India, I found that there was a significant disparity between children of different races and classes and how they were discussed in the sources. For example, the literature only discussed vaccination through a white-English perspective. For the English elite, vaccination was essential to the survival of European children in India. It protected them from the alleged filth that surrounded them. As one guidebook put it, European mothers could not be too careful as Indian nurses, or Ayahs, would be accused of exposing children to the plague-stricken streets of India.[2]

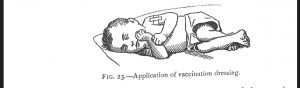

Nevertheless, despite the racism that encouraged mothers to limit their children’s interaction with India or its inhabitants, the truth was that children were exposed to the vaccine lymph thanks to native children. At the time, the easiest and most successful form of vaccination was arm-to-arm vaccination. This means that the vaccine lymph, cow-pox, was first injected into the arm of a child, very likely one of native dissent, and puss would be extracted from that child’s pustule and then transmitted to other children. Vaccinifers, or children used for this purpose, would then travel with vaccinators to different provinces to spread the smallpox vaccine throughout India. These children, unlike the elite children were rarely mentioned in the sources, so much of my time consisted of looking for sources that hinted at the use of native children for vaccination.

This research will serve as the basis of a lecture by Professor Lydia Murdoch next fall in Northwestern University discussing childhood and how it can be used to write history.

[1] Alison Bashford, Imperial Hygiene: Critical History of Colonialism, Nationalism and Public Health, (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014 [originally published 2003]), 33.

[2]A domestic guide to mothers in India, containing particular instructions on the management of themselves and their children. By a Medical practitioner of several years experience in India. Bombay: American Mission Press, 1848.