Alexandra Deane and Quincy Mills

Professor Mills and I began the process of exploring the fundraising strategies of civil rights organizations and the significance of New York City as a critical site of resource mobilization, focusing specifically on the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). SNCC, an organization born out of the lunch counter sit-in movements in early 1960, evolved into a group of students and organizers who sought to build power among black communities in the rural South. In addition to examining SNCC’s strategies of obtaining financial support, I also expanded my research to include archival collections at NYU’s Tamiment Library.

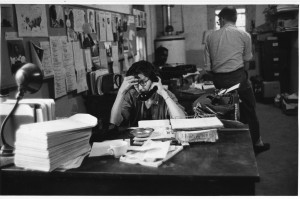

In order to better understand the sources of financial support on which SNCC relied to make their work possible, I combed through the group’s archival papers, which included letters written to and from SNCC staff, reports written by professional fundraisers hired by SNCC, financial reports that detailed the sources of major contributions, and office reports that illuminated the group’s strategic fundraising decisions. I focused primarily on the New York Friends of SNCC office, which was established for the sole purpose of fundraising and amassed the lion’s share of financial support for the organization. Here, multiple narratives emerged about the nature and significance of SNCC’s fundraising strategies.

SNCC relied on the contributions of sympathetic individuals and organizations. Staff established “Friends of SNCC” groups in the North for the sole purpose of fund-raising and developing programming that would simultaneously spread awareness about SNCC’s work and cultivate financial support to send to Southern offices. By keeping their fundraising base geographically separate from their organizing projects, SNCC staff were able to draw upon a larger base of Northern, white, liberal supporters who did not see SNCC’s often radical organizing work in the South as a challenge to their own power. Thus, facilitated by SNCC’s efforts, the “friendship” between financial supporters in the North and organizers and activists in the South flourished.

Throughout these documents, a tension emerges between SNCC’s radicalism and the constraints of their financial support. This tension is perhaps most clear when SNCC chairman Stokely Carmichael publicly embraced the Black Power rhetoric and stance that swept Southern black communities in 1966 and 1967. Responding to the rejection of whiteness (and especially white liberalism) that Black Power politics implied, many Northern supporters quickly voiced their condemnation of Carmichael and SNCC’s direction.

Professor Mills will continue to explore this theme of the tenuous relationship between sources of vital financial resources and the goals and ideals of SNCC, using the results of this project to continue research for his next book, which will look at the sources of financial support for the black freedom movement more broadly.