This summer, I worked with Hadley Sparks on Professor Kathleen Hart’s Ford project focused on translating a 19th-century epistolary novel: George Sand’s Jacques (1833). Like other 19th-century feminist novels, Jacques criticizes the impossibility of divorce under the Napoleonic Code, highlighting a couple’s incompatibility as the basis for their unsuccessful partnership. The inspiration for this project was a preliminary translation of Jacques, produced by the late George Sand scholar Thelma Jurgrau, which provided a set of questions to consider and an initial foundation from which our translations could develop.

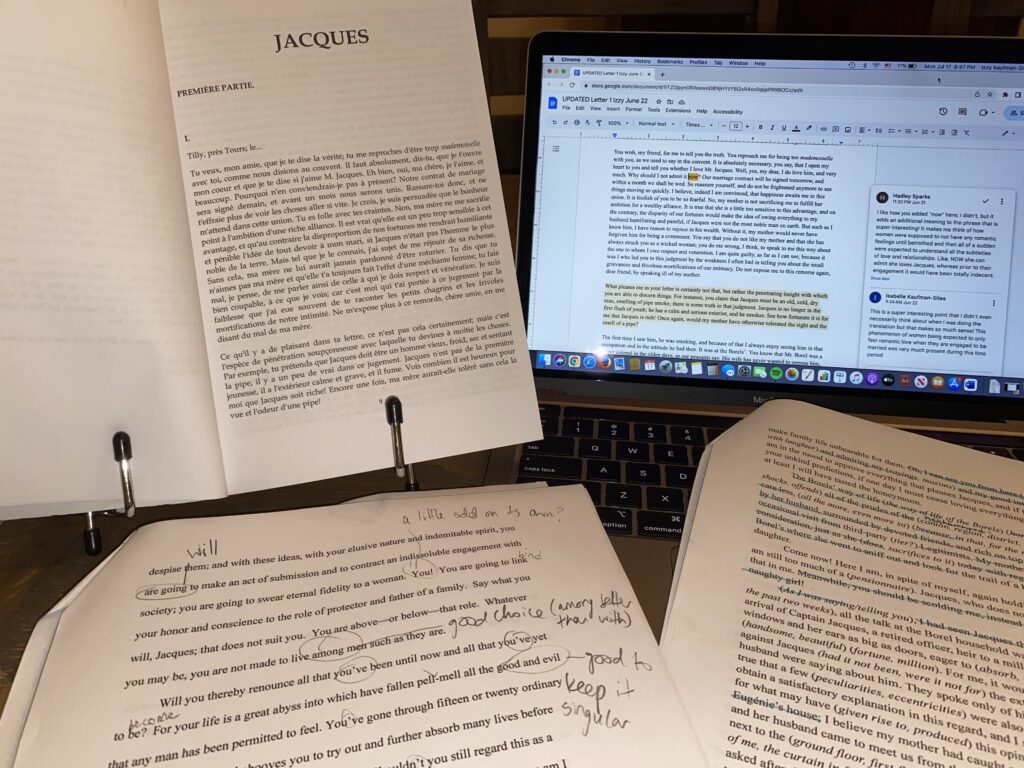

Over the course of the project, we became well acquainted with key principles of translation. We spoke of the importance of maintaining equivalence between the two texts, finding a balance between precise vocabulary and capturing the sentiment and flow of the original sentences. Translation, we also discovered, should not be a solitary process but rather a collaborative one. Examining what in Hadley’s translation was similar to or different from my own—discussing our impressions of the book, methods of translation, and reasoning behind choices—greatly elevated the quality of our work.

We employed a myriad of online resources to help us in our translation process, using WordReference for individual words and Google Translate and Linguée to produce rough translations of the text for necessary alteration. Additionally, we utilized the latest version of ChatGPT to gauge how AI might be able to supplement (though never replace) the work of a translator. We found ChatGPT to be helpful in its speed and ability to produce different versions of a passage, but very limited in its capacity to make translation decisions requiring cultural knowledge and to capture tone or voice.

Throughout her novel, Sand condemns the marriage laws of her time—in particular how they disadvantage women—yet she does not write in an overtly confrontational manner. Indeed, Sand believed that efforts to change society abruptly would hinder the advancement of women, and thus she often distanced herself from feminist causes. Nonetheless, her novel has a feminist subtext and many radical elements. Translating Sand’s Jacques into English offered me eye-opening insights into a subtle form of feminism—and, hopefully, the translation itself will illuminate for a wider audience how a female novelist sought to use narrative to criticize unjust laws and challenge prevailing gender relations in 19th-century France.