Return Migration and Local Labor Markets: Evidence from Mexico

Remy Beauregard and Professor Sarah Pearlman – Economics

I worked with Professor Pearlman on a project examining the effects of a falling US-Mexican net migrations rate (since the 2007-2008 Great Recession) on the Mexican labor market, wages, and employment. Migration between the US and Mexico is a widely-studied migration channel, as Mexico historically sends a significant portion of its migrants to the US. Following the Great Recession, however, this rate fell significantly, with net migration dipping below zero at times. We sought to explore this significant decrease in out-migration and its effects on the Mexican labor force.

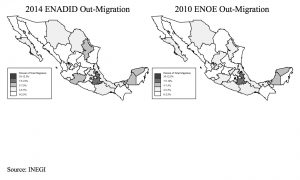

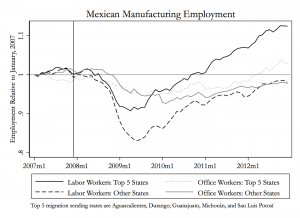

To begin the project, I conducted a literature review to determine the presence of positive, intermediate, or negative selection of Mexican migrants to the United States. I found that significant differences in the literature could be mostly attributed to the systematic undersampling of low-income and low-education individuals and sampling bias. Surveys that took these biases into account found that those most likely to migrate are young males from rural or small-urban parts of Mexico who come from the middle of the education distribution. Next, I used several datasets from the INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía) website, which collects national and state-level data on many economic measures in Mexico. Using these data, I constructed maps of state-level migration rates from two separate surveys and compared them (Figure 1) as well as breaking down the most common reasons for migrants to leave and re-enter Mexico. Finally, in support of the regression results obtained by Professor Pearlman and her co-authors, I constructed employment and salary graphs for different sectors within the Mexican economy to demonstrate the presence of a positive labor demand shock following the period of the 2007 recession, one of which is presented below (Figure 2). While previous literature has examined the effects of a rising net migration rate, our results speak to the opposite scenario and find opposite and anticipated results for a falling net migration rate.

This project was a wonderful opportunity and I am thankful to Professor Pearlman for guiding me through the process of finding and synthesizing all this data. Along the way, I learned LaTeX, mapping, advanced graphing, and many other useful skills applicable to future work in Economics and beyond. I look forward to seeing the final version of this paper and am glad to have contributed.

Figure 1. Out-migration rates for each state in Mexico, as reported by the 2014 ENDADID (Encuesta Nacional de la Dinámica Demográfica) and the ENOE (Encuesta Nacional de Ocupación y Empleo), a time-series and panel data set, respectively.

Figure 2. Changes in employment rates for manufacturing jobs in Mexico, divided between the 5 states with the highest historic levels of out-migration to the United States (noted in the graph) and the remainder of Mexican states, relative to the first month data is available, January 2007. This data is drawn from the EMIM (Encuesta Mensual de la Industria Manufacturera), from INEGI.

*All graphics used were produced in Stata by Remy