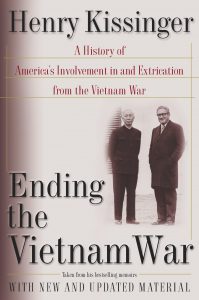

“History presents unambiguous alternatives only in the rarest of circumstances,” writes Henry Kissinger in his memoir, Ending the Vietnam War. “Most of the time, statesmen must strike a balance between their values and their necessities or, to put it another way, they are obliged to approach their goals not in one leap but in stages, each by definition imperfect by absolute standards.”

“History presents unambiguous alternatives only in the rarest of circumstances,” writes Henry Kissinger in his memoir, Ending the Vietnam War. “Most of the time, statesmen must strike a balance between their values and their necessities or, to put it another way, they are obliged to approach their goals not in one leap but in stages, each by definition imperfect by absolute standards.”

Henry Kissinger, President Nixon’s National Security Advisor, was the chief negotiator for the United States in its effort to end—or at least, extricate itself from—the Vietnam War. Between 1969 and 1973, Kissinger met several times with North Vietnam’s Foreign Minister Xuan Thuy and Special Advisor Le Duc Tho in Paris in order to negotiate a peace agreement. Kissinger himself, and several scholars since, have portrayed this process as a careful balancing of “values and necessities,” resulting in an agreement that, though “imperfect by absolute standards,” was the best possibly attainable. In 1973, soon after the agreement was signed, Kissinger was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts.

Yet the agreement was not only imperfect by “absolute standards;” it was imperfect by the only standard that matters: it didn’t work. The only thing it effectively ensured was the United States’ troop withdrawal. The war in Vietnam continued for another two years, and the Government of South Vietnam—after more than a decade of direct U.S. involvement, hundreds of billions of dollars, and over 200,000 U.S. casualties alone—eventually fell.

Working with Professor Robert K. Brigham, the aim of my Ford project this summer was to study the Vietnam peace negotiations (and Kissinger, their leading character) in order to develop a more complete understanding of the defining motives, methods, and mistakes.

I began the summer by reviewing the existing literature: Kissinger’s own memoir (as aforementioned), as well as the Vietnamese account by Luu Van Loi and Nguyen Anh Vu, Le Duc Tho-Kissinger Negotiations in Paris. I also read secondary texts such as Pierre Asselin’s A Bitter Peace; Larry Berman’s No Peace, No Honor; and Jeffrey Kimball’s Nixon’s Vietnam War. Using these sources, I constructed a timeline of the negotiations and discovered several inconsistencies between Kissinger’s account and the others—suggesting that Kissinger has attempted to rewrite and revise the history, thereby casting himself in a more positive light.

At the end of June, Professor Brigham and I travelled to Yorba Linda, California, in order to research at the Nixon Library. In our week there, we found more material than we could’ve imagined—ranging from the State Department’s Vietnam subject files, to National Security Council policy briefs and memoranda, to direct transcripts of the Kissinger/Tho conversations and years’ worth of transcripts from Kissinger’s telephone calls—much of it recently declassified.

We’re still sorting through all the documents we collected—but sometimes, it is just as important to recognize what isn’t there. My personal favorite research discovery was when I found a group of folders that outlined a plan of military escalation against North Vietnam (with the goal of forcing Hanoi to make concessions at the negotiating table). In between two folders that were overflowing with the details of the bombing campaign was a folder titled “Legality Considerations.” The folder was empty.

As we continue to read and analyze all this evidence, one thing is abundantly clear: Nixon and Kissinger were both more concerned with politics and public opinion than negotiating a rapid, legal, and truly reliable peace. In his memoir, Kissinger predicts future criticisms of his negotiating efforts, writing: “It is always possible to invoke that imperfection as an excuse to recoil before responsibilities or as a pretext to indict one’s own society.” In the wake of the Vietnam war, there exists a “credibility gap” between U.S. policy makers and the public—“That gap,” Kissinger insists, “can be closed only by faith in America’s purposes.”

Kissinger asks us to ignore the result of the peace process, and simply trust that the Nixon Administration’s intentions, at least, were pure. My work this summer has only affirmed that (particularly when examining international relations) one should never be so naive—and, more likely than not, the person making such a suggestion is the one with the most to hide.