Jan 31 2010

What’s in a name?

One occurrence of Melville’s literary allusions in Moby-Dick can be seen in his penchant for naming his characters after individuals from the Bible (Captain Ahab and the stranger Elijah). These two examples reflect the embodiment of Melville’s individuals with the Scriptural significance of their stories. Captain Ahab is named after the wicked, malicious king of Israel, who the Bible refers to as the “most evil of all kings that came before him” (1 Kings 16:30). Named after such a reputation, this vindictive personality seems to loom over Captain Ahab, even before the reader is introduced to him. Elijah, the curious stranger Queequeg and Ishmael encounter before leaving port, refers to the Biblical prophet of the same name (Melville even classifies him as such). In Scripture, Elijah is first introduced through his warnings to King Ahab of the terrible misfortune that will come as a result of his evil doings. In Moby-Dick, Elijah serves a similar purpose by warning the two whale-men of the enigmatic sufferer who will be their captain, and the trying expedition ahead of them: “Shan’t see you again very soon, I guess; unless it’s before the Grand Jury.” (Melville, 95). In this way, Elijah encapsulates the Biblical reference of his name. He stirs in Ishmael a sense of apprehension and curiosity concerning his future captain and impending journey.

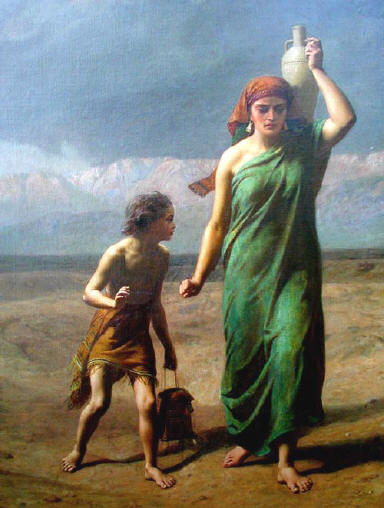

While these two characters are more clearly linked to the qualities their namesakes possessed, Ishmael presents a more interesting study. The name Ishmael calls to mind the story in Genesis of Abraham’s slave-born son, Ishmael. In Scripture, Ishmael is seen in opposition to the spirit of God. The illegitimate son of slavery, there is no place reserved for him in the Family Covenant of God. He is cast out from society, ostracized and shunned by mankind and God himself. However, Ishmael, as the protagonist of Moby-Dick, chooses to purposefully separate and remove himself from the general body of society and the traditions of conventional Christianity by traveling to sea. Ishmael writes, “I am tormented by an everlasting itch for things remote. I love to sail forbidden seas and land on barbarous coasts.” (Melville, 6) His questioning of the mainstream hypocrisy of Christianity can be seen through his friendship with Queequeg, a savage pagan, whom he develops a close relationship with and respect for his hybrid form of spirituality and religion. Although he questions the morality of those who call themselves Christians (such as Captain Bildad), Ishmael does not abandon the religious virtues he was taught; those of compassion to others, ethics and a sense of righteousness. Further reading of Moby-Dick will reveal the full extent and ways in which our narrator embodies the layered references of his name. Perhaps by choosing this name, Melville hints at the unstable role Ishmael may hold in this small society on the ship. As Ishmael questions the veracity of those proclaimed Christian, he may also question the authority of Captain Ahab and jeopardize his place in the journey.

(Melville, Herman. Moby-Dick. Signet Classic: NY, 1998.)

“Call me Ishmael” (1).

“Call me Ishmael” (1).