“Call me Ishmael” (1).

“Call me Ishmael” (1).

From the very moment the reader is introduced to Ishmael, the narrator of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, it is evident that he is no ordinary man-turned-sailor. His request that the reader address him as “Ishmael” forces the reader to consider why he asks to be called this unique name of biblical fame. Perhaps within the world of Moby Dick it is a name and nothing more, but the recurring references to religion and the Bible within the text suggest that many of the character names — Ishmael, Ahab, and Elijah, to name a few — are chosen with a purpose. By investigating the origin and background of these names and their original owners, one can attempt to understand why Melville specifically chose these names as a connection to the references of the Bible and religion (in general) throughout the novel.

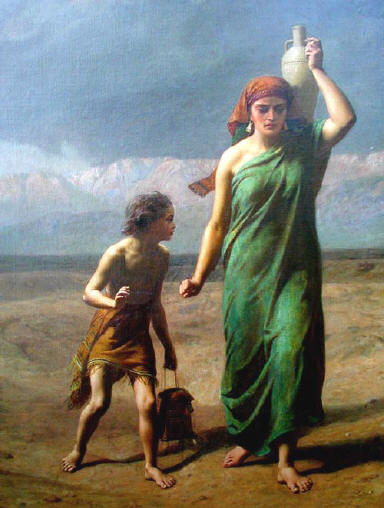

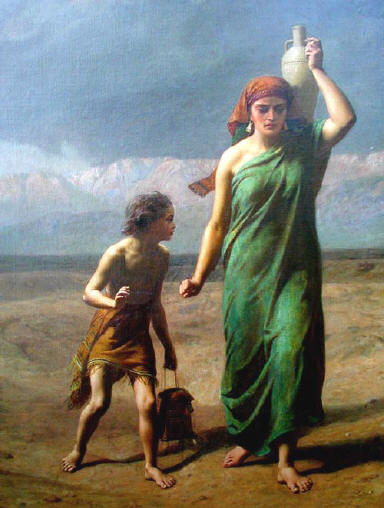

The choice of the name”Ishmael” for the narrator of the story is of particular interest when one considers the biblical character. According to the Old Testament, Ishmael was the son of Abraham, who is considered the father of the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim faiths, and Hagar, his servant. Ishmael was conceived because Abraham’s wife Sarah was deemed too old to have a child. Alas, she did become pregnant with Isaac and, out of jealousy, she banished Hagar and Ishmael. As they departed an angel of God comforted them with the news that Ishmael would lead a great nation. Before he was born, however, it was revealed to Hagar that Ishmael would be a “wild donkey of a man” who would constantly be struggling with others. Thus far in the novel, Ishmael remains somewhat of an enigma but does not appear to be in any struggle with human beings. On the contrary, any struggle seems to lie within himself; for example, he notes that he goes to sea whenever he is close to committing suicide. It is hard to say whether or not the character Ishmael will completely adopt the characteristics of his Bible counterpart. What is clear, however, is Ishmael’s different religious attitudes and thoughts on worship; this will be discussed in another blog post, as I believe it is very important in the novel thus far.

Though the reader has not been introduced to Captain Ahab at this point in the novel, perhaps his biblical name will offer some insight as to what he will be like as a character. In the Bible, Ahab ruled the nation of Israel and was regarded as the most evil and wicked of its kings. King Ahab worshipped the “pagan” gods of his wife, Jezebel, which was viewed as completely wrong in the eyes of the Israelites. Perhaps King Ahab was arrogant and believed he could defy the God of Israel by worshipping other false gods. It will be interesting to see if the character Ahab will also possess this same hubris; time (and extensive reading) will tell.

Chapter 19 of Moby Dick, ironically titled “The Prophet,” concerns an encounter Ishmael and fellow sailor Queequeg have with a mysterious stranger who calls himself Elijah. Elijah warns them about Captain Ahab, hinting that their journey will not end well. In the Bible, Elijah was a prophet of God whose second coming was to be a harbinger of God’s wrath. Melville’s use of the name “Elijah” is very fitting for the character as he does warn Ishmael and Queequeg against sailing with Ahab. Whether his hints of doom for the whaling ship Pequod are true or not is yet to be determined.

Thus far in the novel, it is more than clear that Melville is using biblical names with a purpose in mind. So far, Elijah seems to match the role of “prophet.” Ishmael seems to have some characteristics of his Bible counterpart but thus far he doesn’t seem to completely match up with the Bible’s Ishmael. As for Captain Ahab, little can be determined at this point as he hasn’t been “technically” introduced yet. This connection between the Bible and characters’ names is only a small part of the overall importance of religion within the novel. In my next blog post I will explore Ishmael’s relationship and struggle with religion.

“Call me Ishmael” (1).

“Call me Ishmael” (1).