Mar 03 2010

Ishmael Returns

Why does the Epilogue seem so strange and out of place? In class, we discussed Ishmael possibly distancing himself emotionally from the tragedy that took the lives of his only companions as an explanation for his dead pan description of how he alone survived. Void of the rich, nearly superfluous amount of detail and intellectual insight we have grown so accustomed to in Melville’s narration, the epilogue seems barren and impersonal in comparison.

On the first day of class we discussed how Moby Dick can be compared to a symphony, or a jazz piece. The Novel contains several movements, and following that line of thought, the Epilogue can be likened to calm music that frequently follows the climax of a musical piece. Frequently this final movement evokes the very beginning of the piece, except with a slightly different spin. In terms of narration, I believe that the epilogue is quite like the opening chapters of the book in the sense that these are the only two parts of the book where Ishmael is truly alone. Melville’s mutable narrator is heavily influenced by the cast of characters he is surrounded with. Ahab, Starbuck, and Queequeg are all examples of this, and as such, it is always difficult to discern whats true and what isn’t.

One could read the ever changing narrator as an omniscient presence, shifting from one conscious to the other. For the sake of my argument, however, it helps to look at these shifts instead as Ishmael’s speculations and insights into the characters he is surrounded by. The Epilogue reminds us that Ishmael is writing this account retrospectively, and as such, the means must justify the ends. Perhaps this is why Ahab’s sanity is clearly questioned since the beginning. Perhaps the fact that Queequeg’s coffin saved Ishmael in the end colored his entire perception of the man. Because of this, Ishmael’s narrative embodies the presumed thoughts and feelings of these characters, which have become perverted and polarized in his mind.

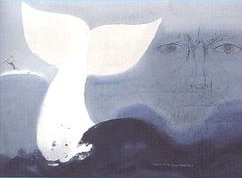

With this in mind, the only times that we really know Ishmael the narrator are the very beginning, and the very end of the novel. Because Ishmael so frequently drifts away from his own thoughts and consciousness, it hints that Ishmael himself is not, or does not consider himself to be, the most important figure in the novel. This explains the brief, and lack luster nature of the epilogue. It also explains the unreliability of Ishmael, as his presence imposes little consequence on the sequence of events, or the messages means to relay to the reader. This again brings me back to the first day of discussion as we considered the opening lines of the book: “Call me Ishmael”. Perhaps what Melville meant by that was that it doesn’t matter who the narrator is, or what he is called. Ishmael merely reflects and analyzes those around him, he was merely burdened with the tale to tell. The tale itself being far more important than the man who chanced to survive it:

And I only am escaped alone to tell thee. -Job