Mar 04 2010

The Sea

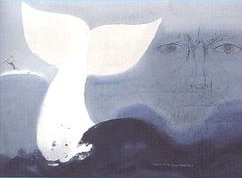

Along with many other things throughout the novel, the depiction and sentiment towards the sea changes along with the shifting narrator, and is also an indicator of the narrators growth.

The omniscient narrator seems to be ambivalent towards the ocean. This is because the ocean is itself ambivalent. Terrible storms and death are carried by the same playful breezes that originate in the tropical air that first stirs Ahab from his seclusion. Melville has personified, and masculinized the sea as the heaving chest of Sampson.

It is also interesting to see the change in Ishmael’s attitude toward the sea from the beginning of the novel to the end of the novel. In the beginning, Ishmael regards the sea as a sanctuary from the perils of life on land. A charming mistress ever enticing him towards the shore. He has many positive feelings towards the ocean, and as such considers it, to a certain degree, a partner of the human race:

If they but knew it, all men in their degree, some time or other, cherish very nearly the same feelings towards the ocean with me. 1

At the end of the novel, however, Ishmael regard the ocean as an unfeeling, ever present entity that allows us to feed off of its bounty simply because of lack of emotion. Ishmael recognizes the immense, impersonal nature of the ocean, and that it was here long before man and will be long after:

Now small fowls flew screaming over the yet yawning gulf; a sullen white surf beat against its steep sides; then all collapsed, and the great shroud of the sea rolled on as it rolled five thousand years ago 551

Notice also the white imagery employed in these final lines. This perhaps hints towards the fact that Moby Dick will always be hunted to some degree in some form or another by someone, just as the ocean will roll on and on. Moby Dick represents the unattainable, and there will always be someone who thinks the unattainable attainable.