When he found out I would be going to Cuba this spring, my 17 year-old-brother’s first comment was to request a certain souvenir: a pair of authentic Cuban cigars with which to celebrate his 18th birthday with our Dad. And he wasn’t the only one to quickly associate cigars with Cuba; “Going to bring back some cigars?” has actually been a frequent question I’ve heard in these months leading up to our departure. And it’s not hard to see why. The Cuban cigar is arguably one of the most recognized symbols of Cuban culture, especially in the foreigner’s perspective. Some of the most widely produced images of Cuban men—both real and fictitious—feature a Cuban cigar.

But what is it that gives the Cuban cigar such distinction in the world of tobacco consumption? And what explains the governments current prohibition on bringing any Cuban cigars out of the country? Helping in part to answer these questions, Daniela Muhor’s essay entitled “Socialism and the Cigar”, offers an insightful look into the operations of Cigar producers and the politics surrounding the industry, especially as they have developed since the economic crisis of 1994.

THE DISTINCTION OF CUBAN CIGARS

A possible, if not probable, explanation for the wide recognition of Cuban cigars as the best in the world is that cigar production is such a long-standing tradition in Cuba that has gradually become intertwined with its national identity. The existence of the Museum of Tobacco in Havana, or the common quip “Don’t tell me the whole history of Tobacco” used to cut off a chatterbox, attest to the prominence of tobacco in Cuban history and to the Cuban national identity. Even in recent years, when the Cuban government and economy has undergone drastic changes, the nature of cigar production has changed relatively little—it continues to be quintessentially Cuban in nature. Small farmers, or cooperatives established by groups of small farmers, continue to be the primary producers of the quality cigars that can fetch prices of up to 500 U.S. dollars per box when sold abroad. Creating a Cuban cigar requires a very specific and thorough knowledge of the entire agricultural process and of the anatomy of the tobacco plant itself—for which many cooperatives of small farmers have hired knowledgeable instructors to educate increasing numbers of employees. And even after initial training, the Cuban tobacco industry has historically been known to emphasize the broader education of its workers, as attested to by the existence of “readers” in cigar-rolling warehouses before the invention of the radio.

In the course of its growth over a period of about six months, each tobacco plant is visited at least 150 times! During that time, the farmers must plow, sow, transplant, fertilize, weed, irrigate, and finally harvest their plants. Next the tobacco leaves are dried out, cured, rolled into cigars (another complicated process in and of itself), sorted by color, packaged, sealed, and shipped. Throughout the entire process, farmers and cigar rollers carefully record the movement of every bit of tobacco to avoid costly waste or theft.

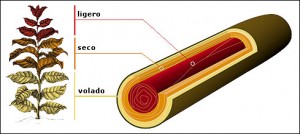

But Cuban cigars aren’t world-renown due only to the dedication of farmers, but also to the expertise of the cigar rollers. Each roller recognizes the differences between the five essential types of leaves included in a single cigar known as capote, seco, volado, ligero, and pica dura. Each comes from a distinct part of the tobacco plant and has a particular role as part of the cigar. Some leaf types such as the ligero are crucial for the flavor of the cigar, while others like the seco are meant to help the cigar burn properly.

CIGARS AND THE POLITICS OF THE REVOLUTION AND THE 1994 ECONOMIC CRISIS

Because the creation of each and every cigar requires an extremely meticulous process, even the crisis-driven demand for higher production couldn’t cause the industry to undergo a transition to the large state-farm model, as so many other agricultural industries experienced. That is not to say, however, that the government has abstained altogether from involving itself in the tobacco industry. Quite the contrary, it has encouraged higher rates of cigar production than ever before by giving producers priority access to agricultural resources (fertilizers, machines, materials, etc.), by maintaining tobacco prices as 10 cents per pound, and by implementing incentives for higher production (particularly by paying producers in part with U.S. dollars, or paying extra for each cigar produced in addition to a worker’s daily quota). And its not hard to see why the government would have an interest in taking these kinds of measures, especially in an economic state of crisis: the cigar industry is second only to tourism in terms of creating U.S. dollar revenue.

And these measure are arguably proving very effective. Between 1996 and 2000, cigar production jumped from 70 million to 118 million cigars made annually. However, the small farmers who dedicate so much effort towards producing cigars aren’t the recipients of the wealth that labor produces. On the contrary, most small farmers cannot subsist off of the revenue made from tobacco harvests, and dedicate only a portion (approximately 30%) of their arable soil for tobacco crops. The rest of their land is reserved for alternative crops, and especially those intended for local sale or auto-consumption. Nevertheless, rural farmers don’t express much resentment towards the limited profits they see from tobacco growth. In fact, many small farmers are fervent supporters of the socialist system of the current government and eagerly embrace the concepts of solidarity, patriotism, and cooperation preached in the socialist model. This enthusiasm to “serve the revolution” explains, at least in part, the tendency of so many small farmers to establish small cooperatives amongst themselves and heighten production. For them, the government’s emphasis on tobacco production not only raises income levels (albeit an disproportional increase to production rates), but it also provides lobbying power when rural areas make requests, such as the establishment of cigar-rolling factories that provides jobs in the community.

Unfortunately, however, the emphasis on high production of cigars in recent years has been cited as responsible for declines in cigar quality. Additionally, as profits from cigar sales rose, and as many Cubans simultaneously became desperate for alternative sources of income during the economic crisis, illicit sales of cigars rose sharply. Many times these black market cigars are of lesser quality, despite the claims of salesmen that they are genuine brand name specimens. This has added to the decline in the reputation of the Cuban cigar among enthusiasts. Currently efforts are being made by the government to minimize the black market circulation of cigars and tobacco products and reinstate the notoriety of the Cuban cigar.

Sources:

Muhor, Daniela. “Socialism and the Cigar,” in Chávez, ed., Capitalism, God, and a Good Cigar: Cuba Enters the Twenty-First Century (Durham: Duke University Press, 2005)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.